ANC deputy president Cyril Ramaphosa wins over the crowd at a campaign rally in Limpopo. He's led people to victory before but he's also made some critical errors.

Malamulele in Limpopo. ANC deputy president Cyril Ramaphosa is ending a long, dusty day of campaigning with a rally in the sort of countryside where anthills grow as tall as men.

“After 24 years [of freedom], we are also tired and it’s time to draw a line. We also want to be part of the economy,” Ramaphosa tells the crowd. “Those who control the compass of the economy” must be reminded, “whether they like it or not”, that more black South Africans want “economic rights, economic power [and] economic control”, he says. The crowd agrees loudly with each point.

On economic transformation, Ramaphosa highlights two issues burning like the November sun beating down on the thousands gathered to support for his CR17 campaign to become ANC president: the return of land to dispossessed black people and mechanisms to ensure that “profits from minerals”, which are leaving the country, are checked. The sun lengthens the shadows. His words appear to lengthen his nose.

Rewind to August 11 2014. It is almost two years since the Marikana massacre when police killed 34 striking mineworkers. Ten men, including non-striking mineworkers, striking mineworkers, mine security guards and policemen were killed in the preceding week at Lonmin’s platinum-mining operation in the North West province.

Ramaphosa, then a non-executive director at Lonmin, is testifying before the commission of inquiry investigating the deaths. His Shanduka Group was, through its company Incwala, Lonmin’s black economic empowerment partner and paid R250 000 a month to “advise” on empowerment.

He had also been chairperson of Lonmin’s transformation committee since November 2010. The committee was meant to monitor Lonmin’s progress in fulfilling its legally binding social and labour plans, like its 2006 pledge to spend R665-million to build 5 500 houses for its employees by 2011. Lonmin failed to do this, claiming it had no money, while it moved, on average, more than R200-million a year during that period to a shelf company it owned in Bermuda — tax free.

During a blistering cross-examination by the Legal Resources Centre’s advocate Tembeka Ngcukaitobi, Ramaphosa admitted that he had not read the reports that showed Lonmin had shirked its legal responsibility to change the lives of its workers. A year before the massacre, Ramaphosa had written an article acknowledging that mining companies’ inability to change the lives of workers was contributing to the instability in the mining sector.

It is a contradiction that goes to the very heart of the man who may be president of the ANC, and South Africa.

Ramaphosa is a former trade unionist, a founding member of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) in 1981. He went on to run some of the longest-running strikes in the country during the 1980s. But, when he was a Forbes-listed billionaire charged with the transformation of a rapacious mining industry, he did little to effect this.

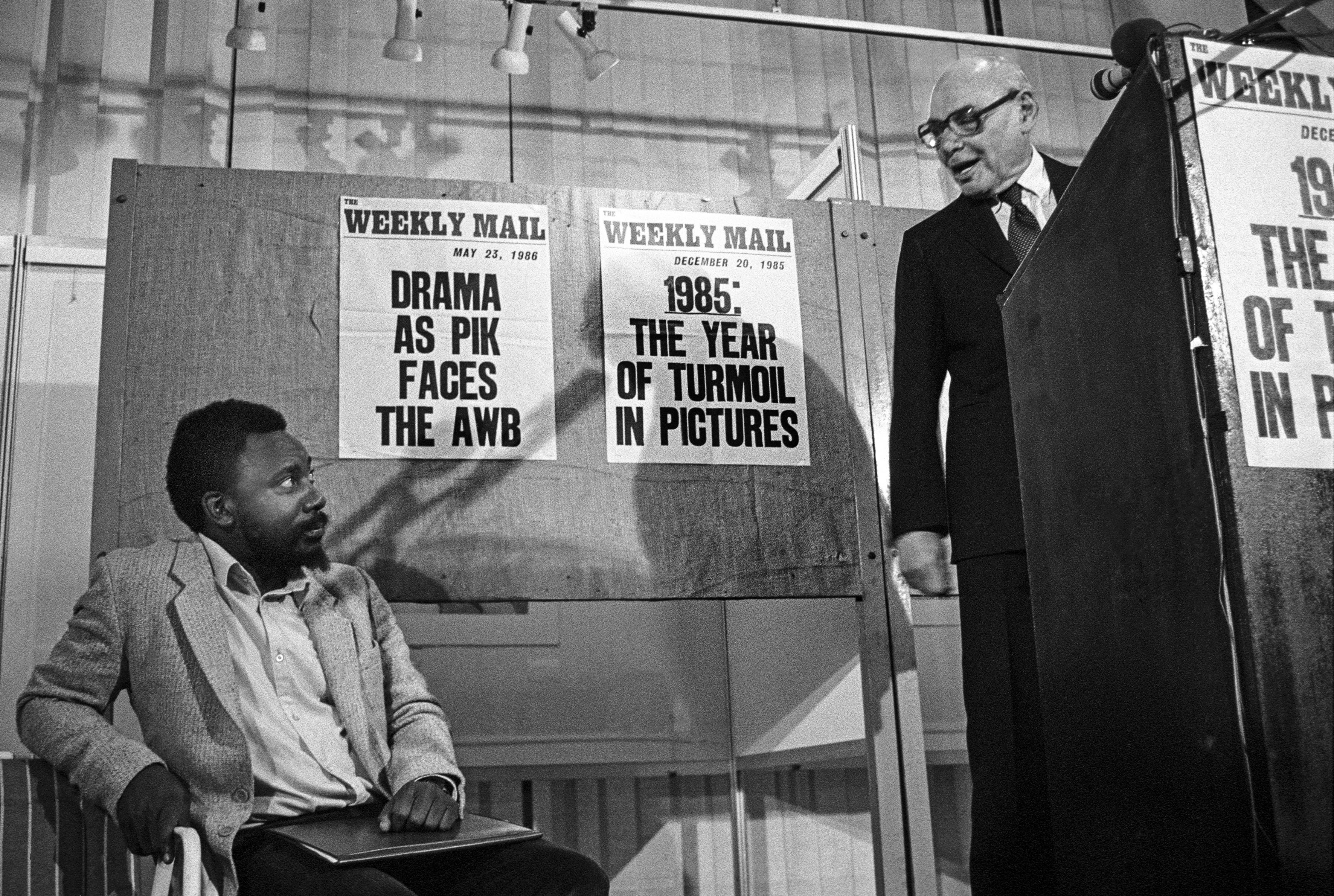

[Two of the country’s most influential people, union leader Cyril Ramaphosa and former Anglo chair Harry Oppenheimer met on a Weekly Mail platform in 1986. (Gille de Vlieg/ South Photos/Africa Media Online)]

What other contradictions live inside the son of a Soweto policeman who, in 1978, at the age of 25, started rubbing shoulders with the Randlords and their scion as a board member of the Urban Foundation? Funded by the mining companies such as Anglo American and Anglovaal, the foundation sought to develop a respectable black middle class in the country.

What dissonance echoes in the thoughts and actions of one of the drafters of South Africa’s progressive Constitution? How did the man once described as “a skilful negotiator” throughout various careers then appear to have gone soft on how business relates to its workers after he moved into the business arena in 1996 as deputy executive chairperson of New Africa Investments Limited?

As results from the ANC’s provincial congresses this week confirmed that Ramaphosa had a slim lead over rival Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma in the ANC’s presidential election race, the question of what type of leader the party may be getting weighs heavily on everyone.

An ANC national executive committee (NEC) member who is supporting Ramaphosa’s candidacy said, of the two candidates, he is the only one “capable of stopping the ANC from imploding”.

“There is a sense of false stability about the ANC and it is close to being destroyed from the inside. If that happens, the country will explode very soon, because people are angry and hungry,” the NEC member said.

Former mining minister Ngoako Ramatlhodi said the ANC is a “damaged organisation” and Ramaphosa would be the perfect antidote because “he cannot be bribed — he has made his money already”. Ramatlhodi says he is supporting Ramaphosa because it is ANC tradition, and “not a cult”, that the deputy president succeeds the party’s leader.

Former NUM general secretary Frans Baleni remembers Ramaphosa telling mine bosses that “only the mineworkers of NUM tell me what to do”. But is he still someone who will stand up to capital in the interests of citizens?

A member of the Legal Resources Centre legal team said they were “astonished” by Ramaphosa’s concession about not reading Lonmin’s transformation reports. There was an expectation he would be more aggressive about ensuring the roll-out of housing, which would have allowed workers to bring their families from rural areas to live with them. This would have addressed the fragmentation of families caused by the migrant labour system.

The lawyer said Ramaphosa may have made the concession because he was concerned about being held “personally liable” and facing potential criminal charges linked to a series of emails he had written in the week leading up to the massacre.

In the emails to Lonmin executives, Ramaphosa confirmed he had asked then police minister Nathi Mthethwa to take “concomitant action” against the striking mineworkers.

“This kind of behaviour is typical of the black capitalist class,” the lawyer said. “They see their role as one of mimicking white capitalists and providing cover and legitimacy for how the capitalists have always behaved. They don’t recognise their transformative duties in the boardroom.”

Another question hanging over Ramaphosa is whether, if elected president of the ANC, he will be an “absent chairperson of the board, clearly not interested in the granular detail” of running the ANC, a party beset with internal problems ranging from careerism to the murder of comrades. Or will he demonstrate the tirelessness evident in building the NUM into the largest Cosatu-affiliated union in the 1980s and steering South Africa towards a constitutional democracy in the 1990s?

Likewise, does he possess the will to turn around a government that has been infected by dysfunction and kleptocracy, and an ailing economy.

Baleni believes he is the sort of “risk taker who sees through” projects to the very end — ideally suited to lifting the ANC and South Africa from its knees.

The view is shared by Mac Maharaj, a former Cabinet minister in Nelson Mandela’s government and former spokesperson for President Jacob Zuma.

It was suggested to Maharaj that Ramaphosa was sulking when he did not show up for Mandela’s inauguration after being overlooked for the position of deputy president in the 1994 government of national unity.

Maharaj said Ramaphosa had suffered a “profound disappointment” at that moment and “we all need time and space to recover from these things … Cyril should be judged on his record since then and there is nothing to suggest in his record that he does not have the capability and the will to succeed in lifting the country and the ANC.”

When Ramaphosa left the ANC, and his position as secretary general, to move into business, the party appeared to be undergoing political purges related to the “resurgence of the exile right” and a consolidation of power by former president Thabo Mbeki and his wingman, Jacob Zuma, according to Ramaphosa’s biographer, Anthony Butler.

“Leftist intellectual” Pallo Jordan was fired from his ministerial post, the reconstruction and development office led by Cosatu leader Jay Naidoo was closed down and deputy minister Bantu Holomisa was “sacked and hounded from the party”, Butler notes.

Ramathlodi remembers consoling Ramaphosa on the 1994 campaign trail in Limpopo where he was running to be premier of the province. “I reassured him that his time would come because seniority dictates how quickly you move into positions in the ANC … Whether he was pleased or not, I don’t know.”

What resides beneath Ramaphosa’s demeanour — approachable, suave, generous and charming — is still difficult to determine, even by those who know him.

He is, as Mark Gevisser noted in a 1996 interview with Ramaphosa for the Mail & Guardian, “charming and unflappable, entirely in control. There’s that smile that wraps itself around his face, that conspiratorial baritone chuckle, that constant engagement masking profound reserve. The most astonishing thing about an encounter with Cyril Ramaphosa is that, even though you know he’s spinning you a line, you — oh, hapless trout! — go for the hook anyway”.