'What happens to us as human beings? Our sense of definition and self-esteem is integrally linked to employment — you must have a sense of purpose

Anyone who has ever earned a living by issuing tickets at a cinema or processing parking ticket payments will attest to the fact that the fourth industrial revolution is here, and it is coming for our jobs.

Bot-proofing your occupation in the golden age of automation — dubbed the fourth industrial revolution — is going to be a tricky business. If your daily work mainly consists of predictable physical activity such as flipping burgers, driving trucks or dispensing medication, the machines are almost certainly coming for your job.

For work entailing a little more thinking on your feet, say as a teacher or a plumber, your position may not be in the firing line — just yet. If you’re a human resources manager — or, better yet, a psychiatrist — it is highly unlikely you could be replaced by artificial intelligence (AI) any time soon.

A recent study from the McKinsey Global Institute has conservatively estimated that, within the next 15 years, 15% of the global workforce — some 375‑million workers — may need to switch jobs. It also found that 60% of occupations have at least 30% of fundamental work activities that could be automated.

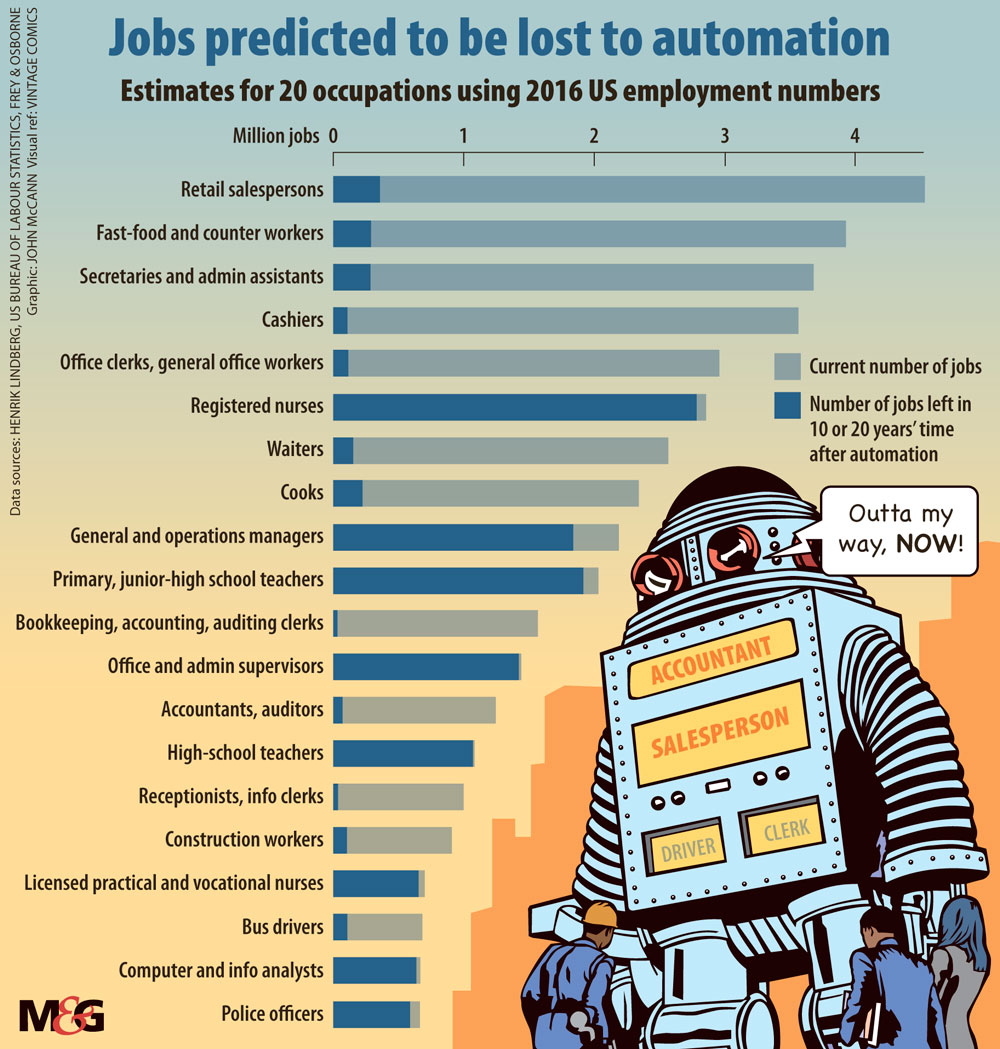

Research from Oxford University expects as many as half the jobs in the world to be taken over by robots in the next decade or two. According to a report by the World Economic Forum, 65% of children entering primary school today will end up working in completely new types of jobs that do not yet exist.

The potential effect of automation on employment varies by occupation and sector, but activities most susceptible to automation include physical ones in predictable environments, the McKinsey report said.

This includes occupations that involve operating machinery, preparing fast food, or installations and repairs. Machines could also displace people who collect and process data for mortgage origination, paralegal work and accounting.

Office support jobs including information clerks, payroll processors and administrative assistants are at risk, as are some customer interaction jobs such hotel workers, travel agents, entertainment attendants and cafeteria workers.

Automation will have less of an effect on jobs that involve managing people and applying expertise, and those (such as customer service) involving social interactions in which machines are unable to match human performance — for now.

Jobs in gardening, plumbing and caring for children or the elderly will also generally see less automation by 2030, because they are difficult to automate technically and often command relatively lower wages, which makes automation a less attractive business proposition, the report said.

One of the biggest remaining technical challenges in automation is mastery of natural language processing, understanding and generating speech, the McKinsey report said.

In the case of translation, machines still have far to go to achieve human levels of performance. They are not yet good at putting knowledge into context, let alone improvising, and they have little of the common sense that is the essence of human experience and emotion.

But to be on the safe side, all workers will need to adapt as their occupations evolve alongside increasingly capable machines. This may require getting more qualifications or spending more time on activities that require social and emotional skills, creativity and high-level cognitive capabilities that are relatively hard to automate, the report noted.

The forecasts are quite alarming for a country like South Africa, which is already suffering from a chronically high unemployment rate as well as a persistent and wide skills gap.

Robots have already begun to replace labourers locally — most notably by mechanisation in the historically labour-intensive mining sector. More AI waits in the wings — for example, retailer Pick n Pay is piloting an automated cashier system that allows for self-service checkouts.

“The notion of a future of work with no work is an oxymoron. You can’t be talking about the future of work when you describe displacement and unemployment,” said Hameda Deedat, acting executive director for labour federation Cosatu’s National Labour and Economic Development Institute.

“What happens to us as human beings? Our sense of definition and self-esteem is integrally linked to employment — you must have a sense of purpose.”

With its high level of unemployment, South Africa could also not undertake an industrial revolution that would displace millions of jobs, she said.

“That’s not the way to go. I’m not against technology, but we must look closely at industries that could benefit … We must harness the potential, determine the pace at which we would like it to happen and in what sectors we want it to happen.”

To date there has been inadequate substantiation of what exactly the fourth industrial revolution will mean for workers and business in South Africa, said Deedat. “From a labour perspective, where there are things happening, in many instances it’s been knee-jerk — there is no comprehensive strategy coming out of this,” she said.

An all-in approach to the fourth industrial revolution forgets that the premise of capital is based on production and accumulation — and that requires human beings to have purchasing power, Deedat said. “These critical questions are not being entered into the discourse. As South Africans, we are going to have to intervene.”

The McKinsey research expects, however, that advanced economies will be most affected because their wages are higher — and so the economic case for automation is better. However, wherever and whenever the revolution does take hold, it is anticipated to create more jobs than it displaces.

Automation technologies, including artificial intelligence and robotics, will generate significant benefits for users, businesses and economies, lifting productivity and economic growth, the McKinsey research found. As such, automation will not only create new occupations that do not exist today but will also drive demand for certain goods and services.

Jobs that are anticipated to grow, according to McKinsey’s analysis, include:

- Care providers: Doctors, nurses, home health aides and other caregivers will be in greater demand owing to rising healthcare spending, thanks to people’s increased prosperity and aging populations.

- Professionals: Accountants, engineers and scientists will be in demand — but supporting occupations, such as paralegals and scientific technicians, may face high automation.

- Builders: Architects, surveyors and cartographers, as well as construction workers, electricians, carpenters and plumbers, work in unpredictable settings and so are less susceptible to automation in the coming decade.

- Technology experts: These specialists will be in demand as automation is increasingly adopted. Technology occupations that require higher levels of education, such as computer scientists and software developers, are less likely to see their occupational activities automated.

- Managers and executives: In all sectors these positions cannot easily be replaced by machines, although some of their more routine activities would be automated.

- Educators: School teachers and others will see a significant increase in demand, especially in emerging economies with young populations.

- “Creatives”: Rising incomes in emerging economies will create more demand for leisure and recreational activities. This, in turn, will create demand for artists, performers and entertainers, although numbers will remain relatively small.

Although the technical feasibility of automation is important, it is not the only factor that will influence how quickly and widely automation is adopted, the McKinsey report explained.

Other factors that will influence its uptake include the cost of developing and deploying automation solutions for specific uses in the workplace, the labour market dynamics, the benefits of automation beyond labour substitution, and regulatory and social acceptance.

South Africa has already experienced resistance to radical changes in “futures-aligned industrial developments”, said the chief director of the Institute for Economic Research on Innovation at Tshwane University of Technology, Rasigan Maharajh.

He was referring to a blockade earlier this year by coal truck drivers that caused traffic havoc in Pretoria. This came after Eskom did not renew contracts with 48 coal transportation companies, partly because renewable energy sources have been successfully introduced into the national energy supply mix.

“The recent experience forewarned of the potential social and political unrest in the making. The net effect would undoubtedly result in an uneven adoption of the new ways of doing things, with especial diffusion in sectors where labour is weakly organised,” he said.

“That notwithstanding, the current world population of 7.6‑billion people are commonly confronted by an accelerating ecological catastrophe that demands transformation of not only what we produce but also what we create, and how these are distributed and consumed.”

A more adequate response to the challenges presented by automation, digitisation, robotisation and AI requires a democratic and developmental state that is truly participative, Maharajh said. Because the country has endured the failures of technocentric policy frameworks, he said the government and the rest of the state must now adopt a more inclusive approach.

“In seeking to act on behalf of its population, government could moderate the impacts of technological innovation by increasing its investments in public research and development,” Maharajh said.

This, he believes, would better equip South African enterprises to respond to advances in science and technology.

Competitive economies adapt to and create new markets and processes to remain competitive, said Tanya Cohen, chief executive of Business Unity South Africa (Busa). Automation will require new technologies that demand new skills and new manufacturing capabilities.

She said many sectors and businesses are already responding to the prospect of an increasingly automated future.

“They are identifying future jobs and how to innovate and be competitive in the new world of work. We are focusing as Busa on how to influence an enabling policy environment that will enable inclusive growth, employment and transformation for the future,” said Cohen.