EFF members protest at the H&M store in the Mall of Africa

A black woman, probably a shopper, traipsing around the aisles with a handbag slung over her shoulder. A throng of white people, feeling trapped inside the same shop, gathered close enough to the window to observe the spectacle outside.

Both, shielded by glass, are momentarily insulated from the chaos. The one, possibly desensitised to the sound of the toyi-toyi, has her back turned to the action, probably still shopping. The group, seemingly terrorised by the scene beyond the glass, look like deer caught in the glare of the headlights.

The fleeting cellphone image immortalises a country seemingly living in splitscreen. Something about the woman’s nonchalance speaks to the reactionary nature of the protest. Something about the shellshocked white people speaks to the enduring image of die gevaarlike aap.

Looking for it two days after the Economic Freedom Fighters’ protests forced H&M to shut the doors of its 17 retail stores on January 13, the video eludes me. Instead, I am confronted by a barrage of tweets by Black First Land First leader Andile Mngxitama. They bear the acerbic sting of sour political competitiveness. He is tweeting about “chasing shadows” and the folly of “fighting individual acts of racism”.

Then comes the ANN7 report about the H&M store at the Mall of Africa in Midrand on January 15. It is one of about seven stores in the Western Cape, Gauteng, Limpopo and KwaZulu-Natal that were trashed or blockaded by members of the EFF, according to the party’s spokesperson Mbuyiseni Ndlozi.

Speaking to the Mail & Guardian on Tuesday, Ndlozi said the protests, following the global furore sparked by Kenyan-Swedish child model Liam Mango wearing a hoodie bearing the words “coolest monkey in the jungle”, constituted bottom-up action from the EFF branches and would continue.

“No meeting is happening,” he said, dispelling talk of a roundtable discussion with the Swedish retailer. “Should they want to come to the table and talk, we’d welcome a step from their part. What you saw online was a response to a [hypothetical] question about, should they want to talk, what proposals would we put on the table?

“We have proposed several remedies like local production, stopping labour brokering, making sure their workers are getting above the living wage … We’d also direct them to

use black models and to spend money on agencies using young black children. It’s a set of things that go beyond an apology. We don’t want an apology.”

On Tuesday, Ndlozi characterised the contact with H&M as “not concrete”, saying the company had written but had not made steps to meet.

The actions of the EFF came on the day the ANC was in East London, cutting a gargantuan cake made by a Democratic Alliance member named Nadine Taylor, shading its former president and feeling optimistic about how much life remained in the ruling party’s blood.

That this was the action of EFF branches working without higher instruction is probably untrue, because EFF leader Julius Malema’s public utterances appear to contradict that: “To say people were sent, you are again undermining black people to say they cannot think on their own. Someone had to carry them and send them there. No one was forced to go to H&M. They were told an idea and they said, ‘Yei! You are right, we are going.’

“The leadership said this is a programme. We think it is reasonable. Let’s get people to go and execute this thing. Fighters on the ground.”

What did strike me was the bravery to pull it off, what with our notoriously repressive police and overly vigilant mall security. It supported the bluster that was to follow from Malema, that of the slow to learn. H&M “being taught a lesson”. Of course, knowing about pseudo-sciences such as eugenics, phrenology, and good old-fashioned biblically justified racism, how do you think I felt about the EFF ground force’s actions?

I don’t give a shit about H&M and their right to trade safely in South Africa or anywhere in the Global South. Off the back of whose child’s labour? For now, at least, the EFF seemed to have kicked them in the balls.

I suspect this may be temporary. Piecemeal, I would say. But it did get me thinking: Just how fractured are we as a society if we cannot agree to vote collectively with our rands, as in the bad days of yore?

I’m not here to debate the “decency” or “savagery” of the EFF’s actions but to ask a more lasting question: At what point do we use our much-vaunted and analysed buying power to send the forces of global racism heading back to

the planet they come from? What happened to the good old consumer boycott?

“For me, it represented a boiling point of bottled-up emotion,” says activist Lehlohonolo Shale. “But then it becomes important to have a civic organisation or a movement which directs that anger to the correct target.

“Racism is as old as the day and in advertising it comes up from time to time. The situation was overt and emotional. It created that outrage. I think that’s how people were able to take up that campaign.

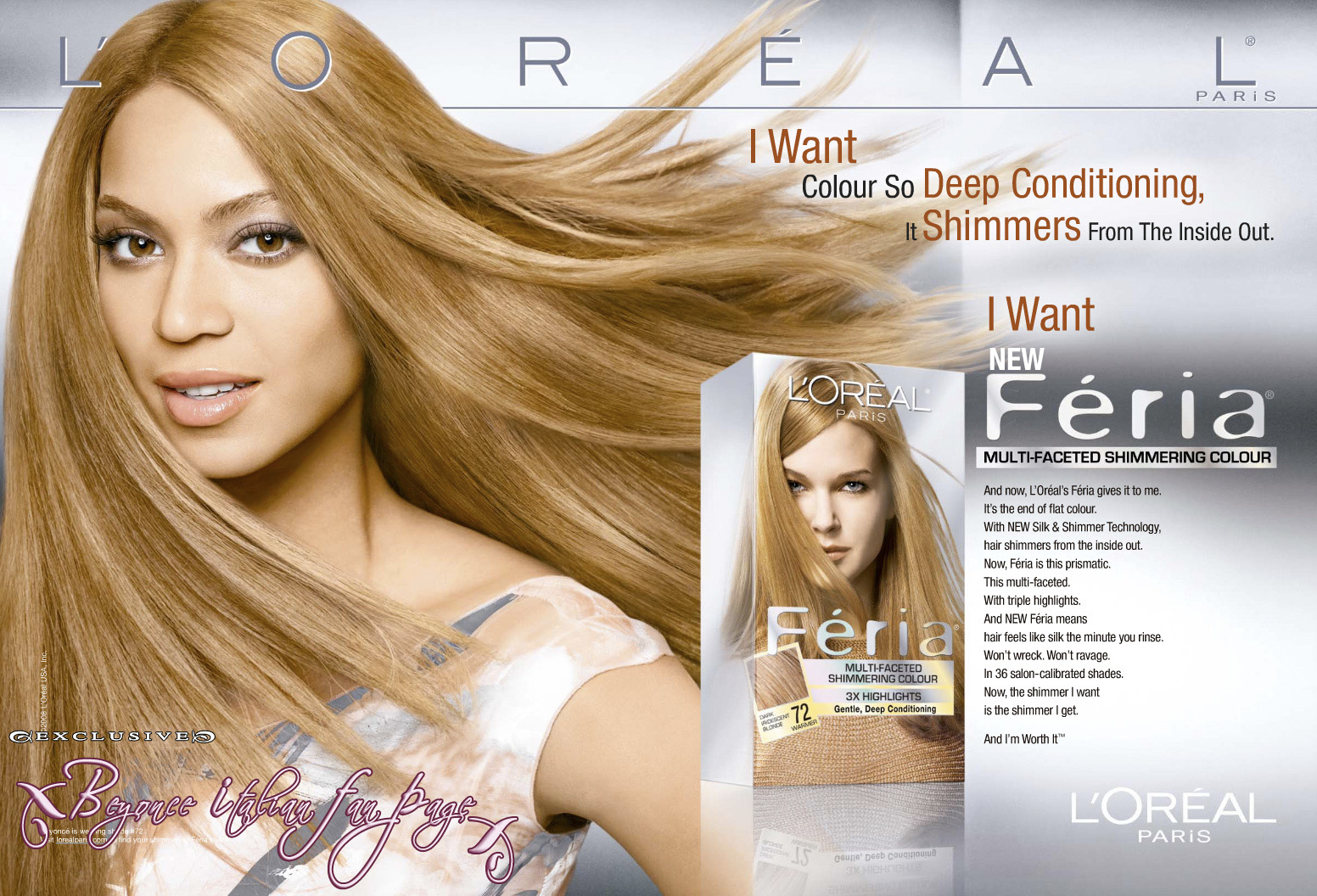

“Christine Qunta wrote a book recently called Why We Are Not a Nation. In it she looks at how brands like Nivea and others continue to undermine black people, even at celebrity level, among stars like Beyoncé [referring to how in a L’Oréal advert her skin was lightened to the point of her being unrecognisable].

“Sometimes it is subliminal, but the point to make is that racism is unacceptable. Whether it is opportunistic or not, somebody must demonstrate, whether by the EFF or anybody for that matter. The struggle has many sides. You have above-ground struggle, like consumer boycotts and so on, and more underground methods.”

The sad part, though, from speaking to Ndlozi, was that the attempt to treat it as a broader labour issue, beyond the emotiveness of racially based slurs, was nonexistent or retrospective at best. Which, I guess, is the difference between party political tactics and a true groundswell of grassroots action.

Ndlozi’s words to me were that the EFF didn’t need the permission of workers to mount a protest against racism; anybody (outsourced H&M workers included) were welcome to join the protest.

What’s clear from the EFF protest is that the fragmentation of the labour movement and the successful silencing of labour federation Cosatu has brought us to a situation where it is easier to throw suspicion at each other than link hands in a march.

Fragmentation can take many guises. Class mobility. The demobilisation of civic groups through repression and the changing political times.

In the Marikana killing fields, the mushrooming of informal settlements made it hard to enforce consensus with the ease that the hostels provided. It was often left to the knobkirrie, the panga or the gun.

“The boycotts initiated by the Palestinian support groups [Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions] against Woolworths, for example, didn’t really pick up but they raised the issue in the public imagination,” says activist, photographer and historian Omar Badsha.

“The other thing is that [in] the township boycotts during the 1980s, we don’t know how effective and sustained they were. Black Christmas and so on, sometimes they were only enforced by tsotsis physically. In England, the anti-apartheid pickets around some companies and so on, those pickets ran for years, but while they didn’t stop anything immediately, they raised the profile of the issue that people wanted to raise.”

Returning power to the hands of the people, though, ultimately takes “building broad fronts”, as erstwhile activist Joanne Yawitch says.

Yawitch, who participated in the Fatti’s and Moni’s and Wilson’s and Roundtree boycotts of the 1980s, says sometimes “you might find yourself in a political organisation, working with a bunch of people whom you might disagree with on a whole lot of other things, but you can agree on this one issue”.

In other words, a Tembisa child being called a monkey in Sandton is in the same predicament as a child being harassed at a checkpoint in Palestine’s occupied territories. We used to see it. In the glaze of late capitalism, we just don’t see it yet.