Like other gifted but tragic music icons

This is a story about music and identity theft.

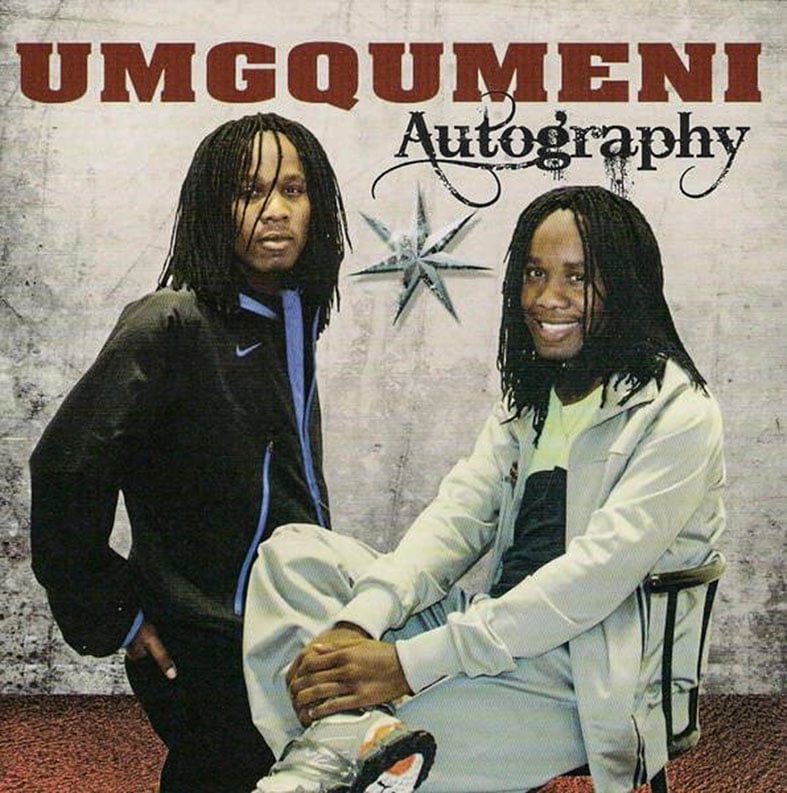

[Two personas: The cover of Mgqumeni’s final album, Autobiograpy]

On the cover of his final album, Autography, there are two uMgqumenis. One is clad in white, right leg crossed over the left, the bottom of a running shoe sneaking into the frame. This uMgqumeni is smiling directly into the camera, as if in an attempt to be carefree. Behind him stands a figure, wearing all black, dreadlocks covering most of his face and hands in his back pockets. Above them, the word “uMgqumeni” is embossed in maroon on a grey background and under that, in Bleeding Cowboys font, is the title of the double-disc album.

Canadian graphic designer Guillaume Seguin released the Bleeding Cowboys font in 2007, inspired by punk rock and grunge bands. I’m not sure what he’d make of his creation being on the cover of a best-selling maskandi album in Africa.

The artwork for this final uMgqumeni album would prove to be prophetic, as if he knew that at some point there would be more than one version of himself and played a little joke on us while he still had time.

II: Lazarus comes to Nquthu

In the summer of 2012, three years after uMgqumeni’s death, just as the maskandi scene was beginning to heal from the ripple effect of his passing, there was an announcement on Ukhozi FM about him. Listeners were about to be treated to an interview with a person who was claiming to be the musician, risen from the dead.

But this “resurrected” uMgqumeni said he had never really died. Instead, he had been captured and held hostage as an umkhovu (a neo-zombie), by whom exactly he refused to say.

“There is not much that I remember; I just saw a bull and everything went black,” he proclaimed during the interview. “I am only finding out what happened now that I’ve been found, that people thought I was dead.”

The story soon went viral, and uMgqumeni fans prepared to make the journey south to see their idol. In a vast open field in Nquthu in northern KwaZulu-Natal, the following Sunday, thousands gathered from as far afield as Zimbabwe, all wanting to get a glimpse of their returned hero.

Filmmaker Nduduzo Shandu was at the scene. “I took a taxi to eNquthu. Everyone in the taxi was talking about the return of uMgqumeni. Some were sceptical; others believed it was him. When we arrived, it was packed. Thousands of people were waiting to see him. I remember one old lady next to me shouted: ‘Hhuye (It’s him)!’ That’s when the media and people went crazy.”

[Despite bearing no resemblance to uMgqumeni, this man (above) surfaced in 2012, claiming to be the late maskandi star, thrilling the thousands of fans gathered in Nquthu (Gallo Images/The Times/Tebogo Letsie)]

This Lazarus did not awaken from the grave. He emerged from the top of a police Nyala in a red floral shirt not unlike the one uMgqumeni wore on the cover of i’Jukebox, plus a cowhide crown, biting his lower lip as he waved to the stadium-sized crowd.

This uMgqumeni didn’t have dreadlocks; nor did he have the oval facial features and big eyes of the artist on the cover of Autography.

The black-and-white footage Shandu caught of the moment is haunting. Some people’s faces are full of hope; others are vacant, haunted and unsure what to do.

“It was like Jesus coming back. Some even cried because they felt that their idol had lost so much weight; others asked him to smile,” recalls Shandu. “They wanted to see his unique charismatic smile. But there was a gang of young boys who were angry and they kept saying: ‘It’s not him.’”

Although some (including one of uMgqumeni’s girlfriends) affirmed that it was him, others were sceptical. But this was his coming-out party and he wouldn’t let anyone ruin it. From the back of the Nyala he charmed journalists as they badgered him with questions.

“My face has changed because of the lifestyle I was living as a zombie, but I am still uMgqumeni,” he said with a smile, surrounded by three police officers operating as his bodyguards. “Some people call me a ghost. I cannot pretend to be somebody else. Some people feel guilty for what they’ve done to me but I love all of you.”

In Zulu culture, when a person has been turned into umkhovu, there is a rehabilitation process that must be followed to reintegrate them into their community. This, according to Bheki Khumalo, uMgqumeni’s paternal uncle, was the reason why when they found this man, they kept him away from people prior to that revelation in the field.

“We were not happy with the state he was in,” recalls Khumalo. “We wanted more time to give him more muthi and help him heal, but there was too much pressure from the public and we knew we had to show him because we had nothing to hide.”

But people had other theories as to why this pretender had emerged. Shobeni Khuzwayo, uMgqumeni’s manager, says he didn’t even bother to go to the field that day.

III: Have you heard from uMgqumeni?

To understand why an impostor would go to such lengths to impersonate a dead maskandi musician, you need to understand the weight of uMgqumeni. And to understand uMgqumeni, you need to understand Nquthu, the rural KwaZulu-Natal village where he was born.

The drive from Durban to Nquthu is harrowing. Almost three hours and the further you go, the bumpier the roads get. In recent years, this place has been stricken by drought. We pass bridges with no water under them, animals dead under barren skies with only their carcasses left to tell of their thirst.

I am reminded of Athi-Patra Ruga’s A Land Without People for a People Without Land tapestry works. Here people have land but because it is so dry, they are forced to relinquish it to the highest bidder to make ends meet. “The people haven’t drank in so long/ The water won’t even make mud,” says a Gregory Porter lyric. In this part of the world, water is holy and so is music. That’s why they use the latter to summon the former.

What you also notice about Nquthu is the absence of men in their 20s to 40s. There are kids and then grandparents. In between is a missing generation: young men pushed out of the birthplace of their forefathers to find work in the cities. Some come home to bury the dead, those left behind. Some come home to be buried. UMgqumeni did both.

As a child, Khulekani Kwakhe Mgqumeni Khumalo was often bullied because he was small and had a high-pitched voice. From a young age, he showed an aptitude for the guitar; music would become his refuge. He competed in local talent shows and won a few. But the bullying got so bad that he decided to leave the village and join his uncle Mahawukela, a popular maskandi musician who toured with legendary maskandi crew Izingane Zoma.

According to music promoter and manager Shobeni Khuzwayo, what made uMgqumeni so good was his ear and ability to pick sounds, a skill he learned from Mahawukela.

UMgqumeni’s songs were mostly written in the first person. Loss, helplessness and failure are recurring themes in his catalogue. As Khuzwayo points out: “He was an artist that had a hard time because he wanted more, and there were things and people in his life that were making it hard for him to achieve happiness. So he would always turn to music to express how he was feeling and I think that’s why people related to him so much.”

On the cover of i’Magic, again two versions of himself appear. One sits on a chair superimposed on an ocean scene like some chilled-out Christ-like figure.

In the world of maskandi, uMgqumeni occupied the sacred place of being both musician and muse. His work has spawned several bands while he was alive and since his death. In the genre, he is considered the avatar of an artists’ artist. Conversely, he was a deeply resented figure among some of his peers.

Maskandi tends to appropriate freely without permission. It’s not uncommon to find a maskandi remix version of a popular song, where an artist changes the chords and uses the lyrics as is, without crediting the creators. UMgqumeni set himself apart from many of his contemporaries by not following this formula. Instead, his music fused elements of isishameni and isichathamiya, where the guitar is front and centre and everything else is built around that and not the percussion. His long, dragging notes gave his music a soulful, sorrowful appeal. It was traditional music, yes, but inventive too.

At the height of his fame, uMgqumeni’s albums went multiplatinum and he would sometimes release up to four records a year, including group albums with his many bands.

He also notoriously feuded with one of his close friends, fellow musician Mtshengiseni Gcwensa. The two, who had grown up together, were in a band until they fought over a song.

“He had given Mtshengiseni his start in the industry and when Mtshengiseni went solo, he started attacking uMgqumeni through his music. We were all surprised by this and it would make uMgqumeni cry that someone who he considered his brother was treating him like this,” says Khuzwayo.

What now seems like a silly misunderstanding led to a lengthy feud, which saw the artists exchanging blows on more than one occasion. It got so bad that they were banned on some SABC radio stations until they made peace.

“It affected uMgqumeni a lot, ’cause he wanted his music to be heard and when radio is taken away from you, your fans don’t hear your music even if you have an album out. He wasn’t even getting booked for some events because of this, so that also didn’t help,” adds Khuzwayo.

On Saturday December 19 2009, uMgqumeni and his band were travelling home to spend some time with their families ahead of the busy festive season. There were also plans for a conciliatory meeting between Mtshengiseni and uMgqumeni that had been brokered by radio legend Bhodloza Nzimande.

UMgqumeni and the band were making their way down from Jo’burg to Nquthu after a pit stop when uMgqumeni began to complain about chest pain. His breathing was laboured and they stopped for him get some air. Barely an hour after he took ill, uMgqumeni would die like a troubadour on the side of the road.

“It is noble to die the way he lived,” says Khuzwayo. But I wonder: What could be worse than a story that never reaches home? He never got to make peace with Mtshengiseni. Like Jim Morrison and Jimi Hendrix before him, this guitar hero was no more. He, too, strummed his last chord at the age of 27 and now the music don’t play nice.

Death is one of the motifs that binds all humans. At least, that is what Will Smith’s character in Collateral Beauty says. But uMgqumeni’s death did not lead so much to unity in his family as it did to chaos. The nature of his death, his unresolved estate and the lack of clarity around the rights to his belongings combined to create a recipe for confusion and uncertainty.

Right from the day he died, there was already infighting. At the funeral, the Mselekus, his maternal family who refused to be interviewed for this story, and the Khumalos were at loggerheads because the Khumalos had insisted on seeing the body but the Mselekus had refused.

According to Bheki Khumalo, this was strange because his nephew had not died in an accident so it was customary for relatives to see and wash the body before burial. “This confused us as the Khumalos. Why were we not allowed to see him? That’s when we became suspicious of the Mselekus,” says Khumalo.

This infighting seems like the type of self-contained, ironic scene that uMgqumeni had vilified through his music. It was the antithesis of the social contract he believed existed between people bound by blood.

IV: Prison as ritual

It’s midmorning when I arrive at New Prison on the edge of Pietermaritzburg. During the 50-minute wait for visiting hours to begin, I notice the women. All kinds. Mothers with three plastic bags, here to see their husbands and sons. Pregnant women on the verge of giving birth, here to provide strength to their lovers. Daughters who simultaneously have to learn the alphabet and the security check procedures in the slammer. Rehabilitation is a buzzword in correctional services but as we wait, I cannot imagine who is possibly being healed by any of this.

The second thing I notice is a guard who leads the visitors in prayer and reads Revelation 2:10. “Do not fear what you are about to suffer. Behold, the devil is about to throw some of you into prison, that you may be tested.”

The walk up to the visitors’ centre is roughly 200m, casual and surprisingly scenic. Manicured lawns are bordered by strong, sharp fences. This is my third time visiting a prison. The second was when my uncle was falsely accused of hijacking and held for nearly three months; the first was a field trip we took when I was in preschool. It was a different time then.

In prison, everything is a ritual. The guards search you, you go through a scanner and they clear you. You’re buzzed into two security gates, you walk across to the main visitors’ building and it’s repeated. Two pairs of socks, five toilet rolls, three oranges. Restriction is part of the ritual. I ask a guard how they arrive at these numbers and she tells me: “It’s just the way it is.”

It’s only then that I notice I’m not carrying anything for the person I’m visiting and that’s why the guards keep scowling at me at every turn. The boy in me who was raised Catholic, with a well-rounded sense of guilt, feels bad. But then I remember I’m not just visiting an impostor who one day decided to impersonate his favourite musician. I’m also visiting a rapist.

The regional court in Pietermaritzburg heard in excruciating detail how an 18-year-old woman was kidnapped and raped by Sibusiso Gcabashe, who was going by the name of Sphamandla at the time, for nearly two weeks. Strangely, it is this rape case that the Khumalos believe is evidence that Gcabashe and the man on trial, who they insist is uMgqumeni, are two different people. They say that their uMgqumeni couldn’t have done this; he was no rapist.

[Identified by his family as Sibusiso Gcabashe, he later appeared in court (below) on charges of fraud for impersonating the popular musician. (Gallo Images/City Press/Khaya Ngwenya)]

“I still firmly believe that whoever raped that girl was not uMgqumeni and it is certainly not the man who is accused of this crime. There is a big conspiracy to get rid of uMgqumeni because of his talent and people want to use him. We won’t just sit by and watch that happen,” says Bheki Khumalo.

In 2012 Sibongile Ngubane had been peacefully living in Soweto with her children when, one day, a slender man with pale skin and trembling hands arrived at her door.

Sibusiso Gcabashe told Ngubane he had no money and was trying to hide from a taxi driver who was trying to kill him and cut up his private parts. “He seemed scared and I had no reason to believe that he would lie about something like this. It was very serious. Only a sick person could lie about such a thing,” says Ngubane.

Although she suspected something was amiss, Ngubane let Gcabashe into her home. He stayed with the Ngubanes for about two weeks. During this period they clothed and fed him, and even gave him some money. After giving her testimony in court, Ngubane tells me how Gcabashe would sit in his room for hours, listening to uMgqumeni’s music.

It was almost ceremonial, she says. “It was the only thing he would listen to, day after day. With his headphones, sometimes, for hours and he would stop only to eat. He just kept listening to uMgqumeni nonstop. We would joke that he was obsessed with him and it turns out to be true.”

According to prosecutors, this is when Gcabashe formulated his plan to impersonate uMgqumeni. This would also explain why Gcabashe has such a strong command of the late artist’s songs.

According to Ngubane, a week into his stay Gcabashe told her that uMgqumeni, who he described as his favourite artist, would be resurrected. “He told us that something special was about to happen, that uMgqumeni would be brought back to life and he would keep making music and be even bigger than before.”

A few days later, Gcabashe disappeared from their household. Ngubane figured he was on the run again, fearing for his life — until she heard on the radio that uMgqumeni was alive. She took her kids to Nquthu and was among the thousands who pitched up on that open field to witness a miracle.

As Gcabashe emerged and addressed the crowd, Ngubane’s stomach turned in horror, realising what was happening. “I thought my eyes were deceiving me. I was shocked. I didn’t understand why this man was telling these lies. Clearly he was not uMgqumeni, yet so many people believed him. It still makes no sense to me.”

The mountain of evidence against Gcabashe as impostor is overwhelming. His brother, two sisters and mother insist that Gcabashe is not who he claims he is. There is the young woman who told the court that he raped and violated her repeatedly before running away and assuming his new identity as the late maskandi musician. There is the psychological evaluation that showed he was fit to stand trial. There is also just simply the way he looks.

Why then, after all this, would he maintain that he is uMgqumeni? I ask Shobeni Khuzwayo this and he stares into the middle distance, sighs and tries to answer the question with some honesty. “This story of the resurrection did not start in 2012 with Gcabashe. It started as soon as uMgqumeni died. There were always rumblings that he has not dead. But I knew he was dead because I worked with the Mselekus even on the funeral arrangements. So I have no idea why Gcabashe would do this and to stick to his lie for so many years. It’s an incredible feat of dishonesty.”

According to Gcabashe’s sister, Thobeka Gcabashe, there is nothing in their family history to explain why her brother became an impostor. “We last saw him in 2005 and only saw him again when the story broke. He has embarrassed us and disowned us in public by saying he is uMgqumeni. I really wish he would just own up and tell the truth because this has been a big embarrassment,” she says.

Gcabashe was sentenced to 22 years in prison after being convicted of rape and fraud. I would not get to meet him in prison because he had been moved to Empangeni, where he would serve out the rest of his sentence. The guards at the New Prison go to great lengths to tell me how good a singer he was. I’ll have to take their word for it. They also only call him uMgqumeni, never Gcabashe.

V: Nobody ever really dies

Neither side of uMgqumeni’s family got to properly mourn their son. Through no fault of their own, they raised Khulekani but were forced to bury uMgqumeni. Their son was no longer their own.

“It’s always tricky when someone is famous because there are a lot of fingers and hands in the pot. That’s why I wish this matter had been handled in a traditional court. ’Cause then the chiefs would have done this the cultural way and things would have been different,” says uMgqumeni’s uncle, Bheki.

It is now five years since Gcabashe emerged from that Nyala and, to this day, he stands by his claim of being uMgqumeni. Once, during an interview from prison, he promised his fans that when he gets out he will release an album, titled iReturn.

We make our way out of Nquthu; the nearly three-hour drive is ahead of us. It feels less like a journey completed and more like we are a ship leaving the dock when the stevedores still have crates in their hands.

Everything is unknowable, and this is what I long for. We pass by rows of houses, vacant land, children in the dust and I wonder what uMgqumeni would have imagined for himself growing up here. Certainly not this kind of infamy in death.