UCT students turned violent this week because of accommodation shortages. About 800 students have temporarily housing.

In an environment where trust is at an “all-time low”, the University of Cape Town (UCT) is beginning its own process of truth and reconciliation to address unresolved tensions over transformation and disciplinary action against student protesters. But it risks further fracturing a university community in which students and the executive are still suspicious of each other.

UCT council chair Sipho Pityana has described the university’s establishment of an Institutional Reconciliation and Transformation Commission (IRTC) this week as “historic”. The IRTC is meant to be UCT’s own version of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), with the aim of helping the university identify where it has failed to transform and how outstanding disciplinary processes against students can be reconciled.

A steering committee of students, staff, workers and the executive was formed in 2016. It met for more than a year to discuss and formulate how an IRTC could work.

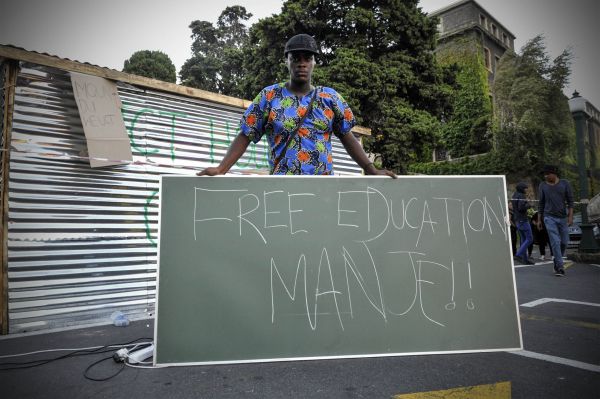

This came after UCT student protesters had demanded a TRC after the #Shackville protest led to five students being interdicted from setting foot on campus, and a number of others being suspended and excluded from the academic programme. During #Shackville, the students erected a shack on the university’s busy Residence Road to highlight housing shortages, and burned artworks in protest against colonial symbolism on campus.

[Shackville protests (David Harrison/M&G)]

Although nearly two years have passed since #Shackville, students and the executive still remain deeply distrustful of one another, and conflict has arisen over the IRTC’s terms of reference. The terms include amnesty for student protesters who had received clemency for breaking university rules, restorative justice in outstanding cases, looking into the #Shackville protest and others, and asking for submissions on decolonisation, labour relations and the university’s culture when it comes to gender inequality, race, sexuality and disability.

Rorisang Moseli, the student representative council (SRC) president from 2016 until mid-2017, was on the steering committee. He fears the burden will be on students to admit their wrongs and ask for forgiveness, and that the university won’t be held to account for its own wrongdoing.

“The process can easily be liberalising if it overdemands those who are victims to forgive,” Moseli says.

Pityana acknowledges that the terms of reference do not create the same expectation of the university management and staff as they do of students, but says the commissioners could change them. The IRTC process, he says, is happening at a time when trust is at its lowest, but he hopes that the commissioners can help students and staff reconcile.

The steering committee recently appointed five independent commissioners to run the IRTC: former TRC commissioner Yasmin Sooka, former Constitutional Court justice Zak Yacoob, gender rights activist Yvette Abrahams, former science and technology minister Mosibudi Mangena and violence and reconciliation researcher Malose Langa.

Pityana admits that the IRTC process nearly fell apart because of distrust between students and the university executive. Last year, the committee deadlocked on a number of occasions over the terms of reference of the IRTC and the deployment of private security guards on campus while the committee was meeting. Students and senate members also accused each another of racism.

Mlingani Matiwane, a student who was the #Shackville representative on the steering committee, says that at one point Pityana got so frustrated that he told students: “We’ll do it without you.”

Pityana confirms there was a period when all stakeholders were on board with the IRTC process, except the students. “I said to them what I said to senate: ‘If you don’t come on board, we will have to move on.’ There was a point where senate also caused problems because they were suspicious of the students,” he says.

The need for a Shackville TRC was proposed in June 2016 by Brian Kamanzi, who was part of the #RhodesMustFall movement to remove the Cecil John Rhodes statue on campus, after five students were interdicted from entering UCT property and could not finish their degrees. A number of others were suspended or academically excluded.

The case of the five students, known as the Shackville Five, went all the way to the Constitutional Court, where the justices upheld a judgment of the Supreme Court of Appeal that the students’ conduct during the protest was “harmful and unlawful” to the university.

Students protested throughout 2016, demanding that the expelled students be allowed to return to campus, prompting Kamanzi to launch a campaign for a Shackville TRC.

Kamanzi says he was ignored at first. It was only in September that the university buckled after prolonged protests, leading to what has now become known as the IRTC.

The IRTC will be very similar in structure to the country’s TRC in that it seeks restorative justice and the transformation of a society, in this case the one at the university.

Although Pityana hopes it will successfully “displace apartheid” culture that lingers on campus, some students remain wary.

Matiwane believes the university set up the IRTC to secure vice-chancellor Max Price’s legacy rather than to genuinely reconcile with students. Price’s tenure ends in June. “I’ve heard that this thing is a legacy project for Max Price,” says Matiwane.

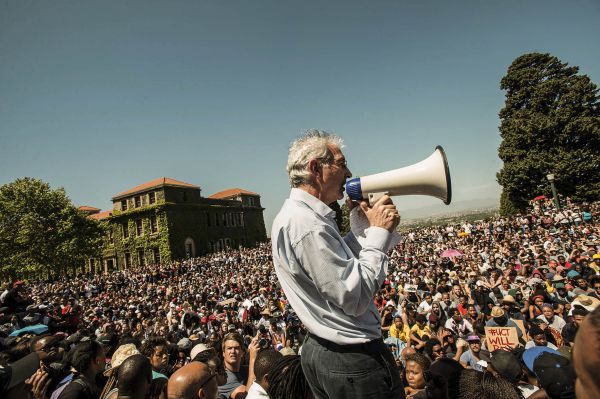

[Vice-chancellor Max Price’s tenure at UCT ends in June, and reports suggest he wants to leave on a high note by embracing the new Institutional Reconciliation and Transformation Commission. (David Harrison/M&G)]

Kamanzi and Moseli say they have heard similar rumours from students and staff. In May 2017, Kamanzi penned an article published by the Mail & Guardian in which he accused UCT of using the IRTC as a “proxy war” to rewrite its history of antagonism with students.

Price was overseas this week and could not respond to questions, but Pityana is confident that the IRTC is an initiative that is bigger than just Price. “The constituencies that brought this to bear are led by forceful leaders who have strong views,” Pityana says. “This ranges from students to workers to academic staff to members of council. If they didn’t want this to happen, it wouldn’t have happened simply because Max Price has deemed it appropriate to have this as his legacy.”

It is unclear when the IRTC hearings will begin but the commission could take up to 12 months to conclude its work. For Matiwane, the IRTC comes too late, because the students most affected by disciplinary processes have already left UCT.

In November 2016, the university and #Shackville students came to an agreement. In order to return to campus and finish their studies, students facing disciplinary action could sign a declaration acknowledging that violent protest was wrong and apologising for their actions. Their academic transcripts would still show that they had broken university rules.

With these agreements in place, Matiwane says there’s no need for amnesty because students who protested in 2016 have now mostly left campus with their degrees — and an IRTC would mean that R5‑million would be spent on a process that had already been resolved.

Pityana says it could even cost the university more than that but adds that if the process succeeds, then the underlying causes of protests, such as inclusivity, would be dealt with.

Although Matiwane maintains a bleak outlook on the IRTC, Moseli believes it can work. The danger he sees, however, is that once it concludes its work, it will be up to the university council to decide what recommendations will be implemented.

“My greatest concern is that this lands up in a really protracted process that ends up in a report that isn’t implemented or has no consequences, just like our own TRC within the country,” Moseli says.