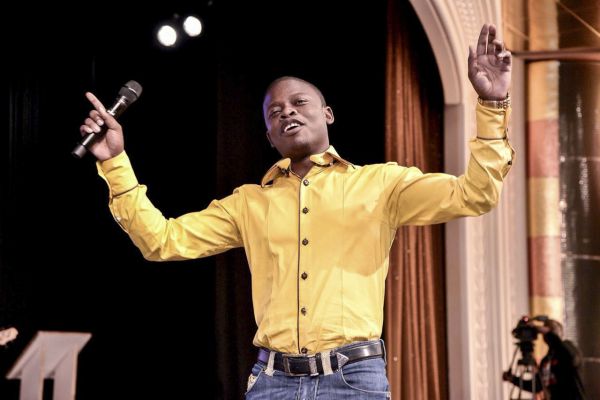

Church of God congregants await spiritual healer Samuel Radebe.

Pretoria showgrounds, Sunday. Church is in service and tens of thousands of people are seated in the main hall, and thousands more watch on large television screens in giant tents outside.

Congregants walk between the aisles to hand over envelopes. In them are tithes and seed payments, usually for a particular blessing. A young woman walks around waving a speed-point machine for those who do not have cash.

There’s a man selling a prayer booklet and a book titled Make Millions in Forex Trading by Prophet Shepherd Bushiri.

[Shepherd Bushiri promises, and makes, profits, as do others in the religious sector (Facebook)]

On the screen, scenes are being relayed from the main hall of people giving testimonies about how, for example, after years of struggling, a woman secured employment; how someone was cured of an illness; and how a man secured millions in investments.

All of this followed a blessing or a prophecy by Bushiri, known to his followers as Major One.

There’s mention of anointing oils, which will enhance healing, add value to your life, “promotions” and “enlightenment” and sell for between R20 and R140.

One remarkable testimony is given by three men who say they received R750-million from a car company to start their bus transport business — this after Bushiri had, in 2015, prophesied that they would own a fleet of 300 buses.

“So you came here with nothing?” asks the official facilitating the process.

“We had nothing; no experience, no company,” one man replies. “When we presented to Mercedes-Benz South Africa, it was a shock to them. They said, ‘This is not normal we can’t.’ But Mercedes, with the grace that was from the favour oil, took a risk and said we are going to offer you R750-million,” says the man as images of the buses flash on the screen.

Then Bushiri makes an unexpected appearance.

“Do you know why I’m here?” he asks. “Wait, we must start again this testimony because I’m about to release an anointing of a national breakthrough,” he says to a chorus of “I receive” and “I connect” chanted by the assembly.

“At ECG [Enlightened Christian Gathering] we don’t attract millionaires, we make millionaires,” he says, before making the man again recount the R750-million miracle.

Meanwhile, at the Revelation Church of God in downtown Jo’burg, testimonies are being screened. Images of what looked like eyeballs flash on the screen.

One of the congregants says the man testifying vomited up the eyeballs after drinking blessed water.

Outside the packed church, hundreds of congregants wait in a holding area and on the pavement to get inside.

None can be found without bottles of water. They bring water from home in their own bottles — or they can buy a bottle from the church.

Money changing hands

A 2017 report by the Commission for the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Cultural and Linguistic Communities said there was prima facie evidence showing that religion has been commercialised.

Thoko Mkhwanazi-Xaluva, the chairperson of the commission, said the investigation had found a lot of profit was being made in the sector.

“Part of it is what they call faith-healing products — [and] out of that you find that there’s a lot of money changing hands,” she said.

The coexistence of religion and trade is not uncommon. It is not against the law. But not paying tax on trade receipts is, which is why the South African Revenue Service (Sars) is launching a tax noncompliance investigation into the sector.

According to a statement by Sars, while most religious leaders and organisations are tax compliant, there were reports suggesting some are not and are instead enriching themselves unlawfully.

It’s unclear how big the sector is. Senzo Mkosi, the acting Sars spokesperson, said this was largely because some institutions were single entities with multiple congregations and others were made up of independent congregations and bodies. He said it was difficult to determine what tax was being paid.

Mkhwanazi-Xaluva said some of the religious organisations that appeared before the commission were making a profit of about R1-million a month by selling products. “It’s quite a big industry, I must say. It’s an industry on its own.”

She said another difficulty was that some institutions were hiding trading profits as donations. “They will say donate R20 and I will give you this bottle of water. That’s how they cover it. But, I mean seriously, if I don’t give you the R20 I am not getting the bottle of water.”

Churches plead ignorance

Leaders in the religious sector have welcomed the probe but said there was a lack of information about tax noncompliance.

Michael Swain, the executive director of the Christian lobby group, Freedom of Religion South Africa, said they advocated tax compliance and proper financial accountability but were aware that it wasn’t happening in some cases. “It was due to a lack of understanding of relevant legislation and regulatory requirements,” he said.

Mkosi said a critical part of Sars’s review of the sector would include educational activities, “because the desire is that all such entities comply with all tax legislation on a voluntary basis”.

The Revenue Service would also ensure that religious institutions are registered with Sars, approved for exemptions, registered to pay pay-as-you-earn tax (PAYE) for all employees and that all trading activities are taxed correctly.

Mkosi said: “If we find cases of abuse, there are various powers that Sars has which we will be utilising.”

This included raising estimated assessments and using the legal tools Sars has at its disposal to collect the debt.

“All entities, including religious institutions, are reminded that failure to deduct and pay over PAYE is a criminal offence,” Mkosi said.

The head of the Revelation Church of God, Prophet Samuel Radebe, said he was happy with Sars’s approach — not with that of the commission.

He refused to appear before the commission and accused it of bullying because it had summoned leaders without “proper consultation”. He also ignored the commission’s request to see his bank statements, because it was not mandated to view them, he said.

“I was one of the first religious leaders who, from the onset, asked why the commission did not rope in Sars if it’s probing issues of money. I would have complied,” he said.

Radebe’s church is known for miracle healing with blessed water and holy salts. These can be bought from the Ubuhle Bencwadi bookshop at the church.

Radebe said: “Everything in the church that could be perceived as being profit making is sold in our bookshop, which is registered for tax.”

Church employees also paid income tax on their remuneration, he said.

Prophet Paseka “Mboro” Motsoeneng, another vocal opponent of the commission who also refused to provide his financial statements, also welcomed the investigation but declined to comment further. He said he needed to consult his accountants first.

Mboro has consistently denied that his luxurious lifestyle is funded by the church and has said he has construction and funeral parlour businesses.

At the ECG sermon on Sunday, Bushiri denied several accusations being levelled against him, including unduly benefiting from church donations.

Bushiri said he was a businessperson and, during a recent trip to the United States, he bought three hotels, which collectively cost more than $450-million. He told the assembly that there was no amount of offerings in the world that could add up to that.

Radebe defended his wealth, saying there was a misconception that religious leaders were making money from fleecing church congregants. He said he had businesses other than his work as a prophet, such as breeding racing pigeons.

Last year, he and his business partners made headlines after they bought a racing pigeon for R5-million.

He said his pigeons were sold in international bids and recently he sold one for R132 531 and another was bought for R142 545.

“We need to ask what are the rights of religious leaders when it comes to money,” Radebe said. “We have a right to be religious leaders but we also have a right to be involved in business. We must ask, what are the limits? How do we measure the success of religious leaders, and what do we classify as wrong, and there is wrong, but what’s happening now, especially in the media, everything is wrong,”

Tebogo Tshwane is an Adamela Trust trainee financial reporter at the Mail & Guardian

Collection bowls are exempt, trade isn’t

Religious organisations are exempted from paying tax if they register with the South African Revenue Service (Sars) as a public benefit organisation.

Senzo Mkosi, the acting Sars spokesperson, said religious institutions were not taxed on their receipts and accruals, except when they came from trading that was not integral and directly related to the sole objective of the entity.

“Sars is concerned that proper taxes on trading activities that are unrelated to religious activities, as well as pay as you earn on remuneration and other benefits are not being paid in terms of legislation,” the revenue service said.

Donations are free from donations tax and bequests are exempt from estate duty. This means what is put in the collection bowl or a tithe is tax exempt. Properties used for religious purposes can also be acquired without transfer duty being payable.

To qualify for these exemptions, religious organisations must meet certain criteria such as, but not limited to, carrying out activities for altruistic or philanthropic intentions.

The activities shouldn’t directly or indirectly enrich individuals, who are only entitled to reasonable remuneration for services provided.

Mkosi said Sars had not defined “reasonable remuneration”. But the Income Tax Act states that remuneration should not be paid to any employee, office bearer, member or other persons that is “excessive”, particularly when compared to what is considered “generally reasonable” in the sector for the service rendered, and does not “economically benefit any person in a manner which is not consistent with its objects”.

At the same time, religious institutions are prohibited from directly or indirectly distributing funds to any person other than those performing their religious duty. — Tebogo Tshwane