(John McCann)

As the dust settles after almost two weeks of uncertainty regarding the fate of Jacob Zuma, President Cyril Ramaphosa must face the unfinished business left behind by the former president’s administration. Nowhere will this be more apparent than in the Budget Speech on February 21.

Investors and ratings agencies will seek clarity on the government’s plan to boost economic growth, the budget deficit and the state’s debt levels, and how the state plans to deal with the financial position of state-owned enterprises such as Eskom. Other major issues are how the state can plug the estimated R51-billion revenue gap, while also coping with unbudgeted expenses such as free education for poor and working class students.

Ratings agency Moody’s has said it will decide whether to downgrade South Africa’s local currency after the budget. On Thursday it said it was monitoring developments, including how the new leadership responded to South Africa’s economic and fiscal challenges.

But with a new president, there is renewed optimism that the economy will get back on to steady footing. The rand continued its gains on Thursday morning after Zuma’s resignation and reached R11.63 to the dollar, levels not seen since January 2015.

There is also the question of whether Ramaphosa will reshuffle the Cabinet and replace Finance Minister Malusi Gigaba. But political analysts believe this unlikely.

“The delivery of the budget really had to be done at this moment given the time frame. It should be presented by the current minister. Thereafter, he can be moved, depending on what the president will decide,” analyst Shadrack Gutto said, as interrupting the budget process at this late stage could cause a crisis in the economy.

Ralph Mathekga, a political economist, said it was unlikely there would be a Cabinet reshuffle before the budget. Ramaphosa had limited space to manoeuvre and could not remove all the ministers who served under Zuma, said Mathekga.

Keeping Gigaba in the post was unlikely, he added. “It’s difficult to sell him. I don’t think people will go for it. He has come up and through a very controversial project.”

But Ramaphosa would have to show change in key portfolios such as finance, foreign affairs and state security, Mathekga said.

Last year’s medium-term budget policy statement (MTBPS) underscored many of the difficulties facing the economy and the state’s finances. But it provided little indication of how they would be addressed.

In a note earlier in the week, Nedbank economists Nicky Weimar, Dennis Dykes and Isaac Matshego said the budget would have to plot a clear path to fiscal sustainability, as its outcome would determine whether Moody’s followed other major ratings agencies’ downgrades.

Growth was expected to pick up in the coming three years, they said, offering more support to the government than was forecast in the MTBPS. Given positive political developments, the treasury was likely to make upward adjustments to its growth forecasts, they said.

But unless economic growth is raised significantly, the government had to make hard choices about its spending priorities to reduce the budget deficit to below 3% of gross domestic product (GDP), they said.

In light of growing social demands and mounting public discontent, the temptation to yield to spending demands would probably increase ahead of 2019 elections, they said, heightening the risk of overshooting expenditure estimates remains high.

Nedbank expected government expenditure to increase to R1.7-trillion, for the 2018-2019 year, and to R1.8-trillion and almost R2-trillion in the following years. This would take the budget deficit to 3.9% of GDP, 3.5% and to 3.1% respectively.

At the same time, the gap in revenue predicted in the MTBPS could tighten the screws on government, with many arguing that tax increases of one form or another are inevitable. This is particularly the case with the introduction by Zuma of free higher education.

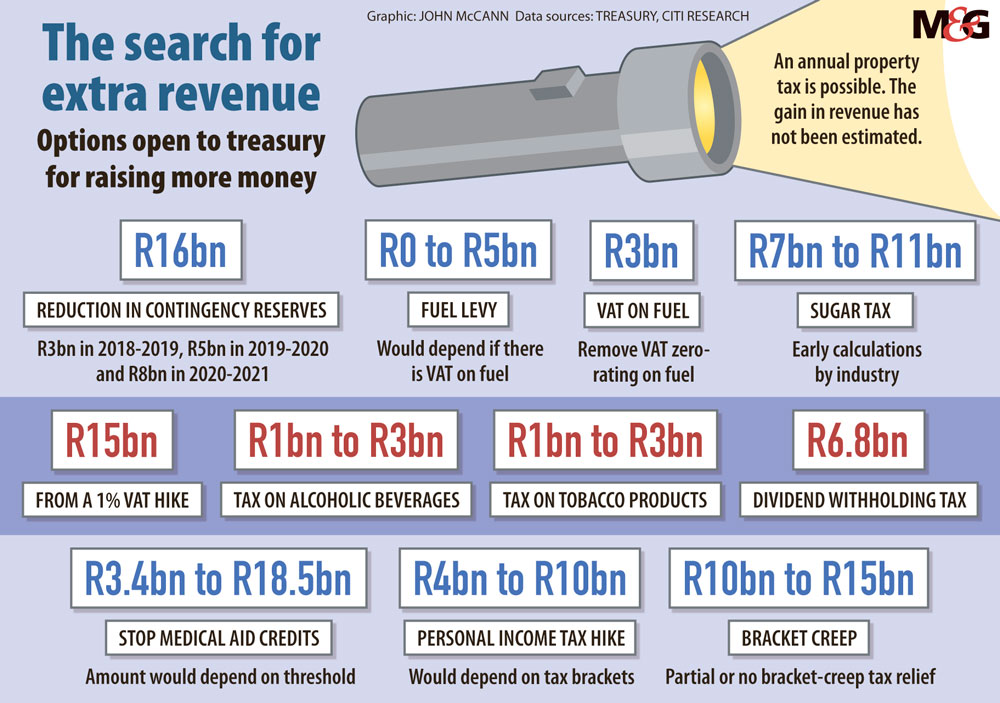

In a report late last year, Gina Schoeman, an economist at Citibank, highlighted the difficulty facing the treasury, pointing out that the MTBPS cautioned against significant tax hikes. But the alternative — expenditure cuts — sounded simpler than it was because of the sociopolitical implications, she said.

She outlined some ways the government could raise revenue. An increase in the value-added tax (VAT) rate, currently 14%, has been cited as a simple way to raise a great deal of money. But she said this was unlikely, given that the Davis Tax Committee had found that a hike is only feasible when economic growth is robust. In addition, the sociopolitical climate would not permit this cost, “particularly for low-income individuals where job growth is scant and indebtedness high”, she argued.

The South African Revenue Service this week said raising VAT would risk dampening household consumption, which accounts for 60% of the GDP. This in turn would have a dampening effect on other taxes, such as company income tax, as profitability could be affected.

A more likely option was the remo-val of zero-rating on fuel, which is subject to a fuel levy. Its introduction would mean a freeze on the fuel levy.

It was also likely that personal income tax would see changes, notably little or no relief provided for bracket creep. Schoeman said this could raise between R10-billion and R15-billion. — Additional reporting by Lisa Steyn