Survival: Nasm Ugerama's baby is due in a month.

Rumana Akoob in Eastern and Southern Provinces, Rwanda

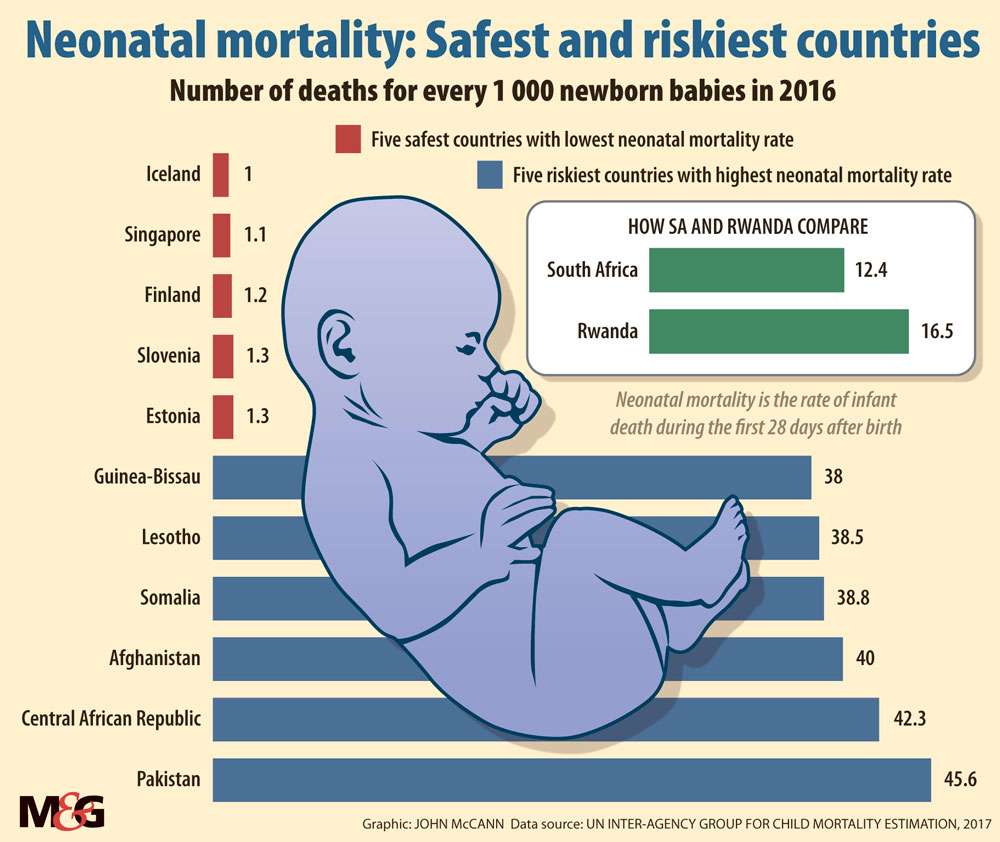

A new Unicef report reveals a horrifying statistic: in lower-income countries, 27 newborns out of every 1 000 die before they are four weeks old. In developed countries, that figure is 3.3 in 1 000.

“While we have more than halved the number of deaths among children under the age of five in the last quarter century, we have not made similar progress in ending deaths among children less than one month old,” said Henrietta Fore, Unicef’s executive director. “Given that the majority of these deaths are preventable, clearly, we are failing the world’s poorest babies.”

Finding a way to drastically lower the newborn mortality rate in lower-income countries to that of developed countries could save 16-million lives by 2030. Fortunately, it’s not rocket science and, in Rwanda, there is a model to show how it can be done.

In 1990, even before its genocide, the newborn mortality rate in Rwanda was 40 newborns for every 1 000. Today, that number is 17.

It is women like Euphrasie Abinogera (57), who have driven the positive change. She is a health worker in the Southern Province village of Gisasa, which is home to 1 011 people. Villages are mostly self-reliant for food, and each home has a lush garden planted with plantain, vegetables and herbs. Every plot of land along the gravel road is either cultivated or occupied by a home. The air in Gisasa is clean and frequent rain gives the village a sharp, earthy scent.

[Community health workers, such as Euphrasie Abinogera, have helped reduce infant mortality rates by regularly visiting and advising women in the villages of Rwanda (Rumana Akoob)]

The closest clinic is a 45-minute bicycle ride away, which makes Abinogera the nearest thing to formal healthcare, even though she is an unpaid volunteer.

Among her responsibilities is to check up on pregnant women and to encourage them to go for antenatal care at least four times before delivery. After children are born, she reminds mothers to visit the doctor and to take their children for immunisation.

These seem like simple things but in a dysfunctional healthcare system they can make the difference between life and death.

Gisasa is spread out over a large area, making it difficult for Abinogera to get around. But she says the job is rewarding, and regular training expands her education.

“It is difficult to visit all the households without a means of transport but I have the will and this motivates me,” she said.

Abinogera is part of a network of 45 000 community health workers who focus specifically on mother and child care. She was chosen by her peers in the village because she is literate and well-respected. Her job also includes collecting data on women who are of childbearing age. She advises them to come to her as soon as they suspect they are pregnant.

When mothers are ready to deliver their babies, she takes them to the clinic herself. The gravel road there is dusty and the terrain is hilly. The only electricity is from solar power or batteries, which makes night-time deliveries especially tricky.

“Challenges are night operations because we need a bicycle to take the pregnant woman to the health centre. I then follow running, until we reach the centre,” she said.

One technological innovation helps to bridge the distance for Abinogera and other health workers. The RapidSMS system, a Unicef initiative, which has been embraced by the Rwandan government, is a real-time monitoring system designed to track maternal, newborn and child health outcomes. Through their cellphones, the health workers can get guidance, reminders and feedback about their work.

Since being scaled up in 2012, RapidSMS tracks nearly 400 000 pregnant mothers and newborn children each year, according to Unicef statistics.

Christine Nyiramana, another health worker, has been working with the Nyamata community in the Bugesera district for the past seven years. She explained how she had used the emergency feature on the RapidSMS system just the day before for a woman in labour who needed to have a Caesarean section.

The presence of community health workers such as Abinogera and Nyiramana helps to calm expectant mothers, who have few other avenues for advice and medical assistance.

Nyiramana visits Nasm Ugerama, who is eight months pregnant, every week. They sit down together in Ugerama’s one-bedroom home, which she shares with her daughter and husband, and go through books with diagrams, which explain what will happen when she goes to a healthcare facility for checkups.

Ugerama’s first child was born six years ago, and she says much has improved in the healthcare system since then.

“We are advised on a wide range of things relating to our pregnancy. I also visit the doctor more often and get more rest. With all the advice I get about my pregnancy, I know the baby feels happy in the womb and can play,” she said.

Unicef has commended the Rwandan government’s progress in combating neonatal mortality and has suggested that its strategy — combining an extensive network of community health workers with technological innovation — can be a model for other countries.

Rwanda has also succeeded in making healthcare for new mothers affordable. Charges are based on an individual’s socioeconomic position. The very poorest don’t pay at all.

In 2013, Rwanda spent 11.1% of its gross domestic product on healthcare, according to a USAid report — the average for other low-income countries is just 5% of their GDP.

There also needs to be the political will.

“Health is generally considered one of the key pillars to development and children are particularly vulnerable … There is a strong commitment by the government of Rwanda to focus on critical health issues and child survival,” said Ted Maly, the Unicef representative for Rwanda.

“It is both a reflection of the overall health system and a way to track development.”

Rumana Akoob is a Daily Vox reporter and travelled to Rwanda courtesy of Unicef