Dead end:The Zuma clan dominates local politics in KwaNxamalala

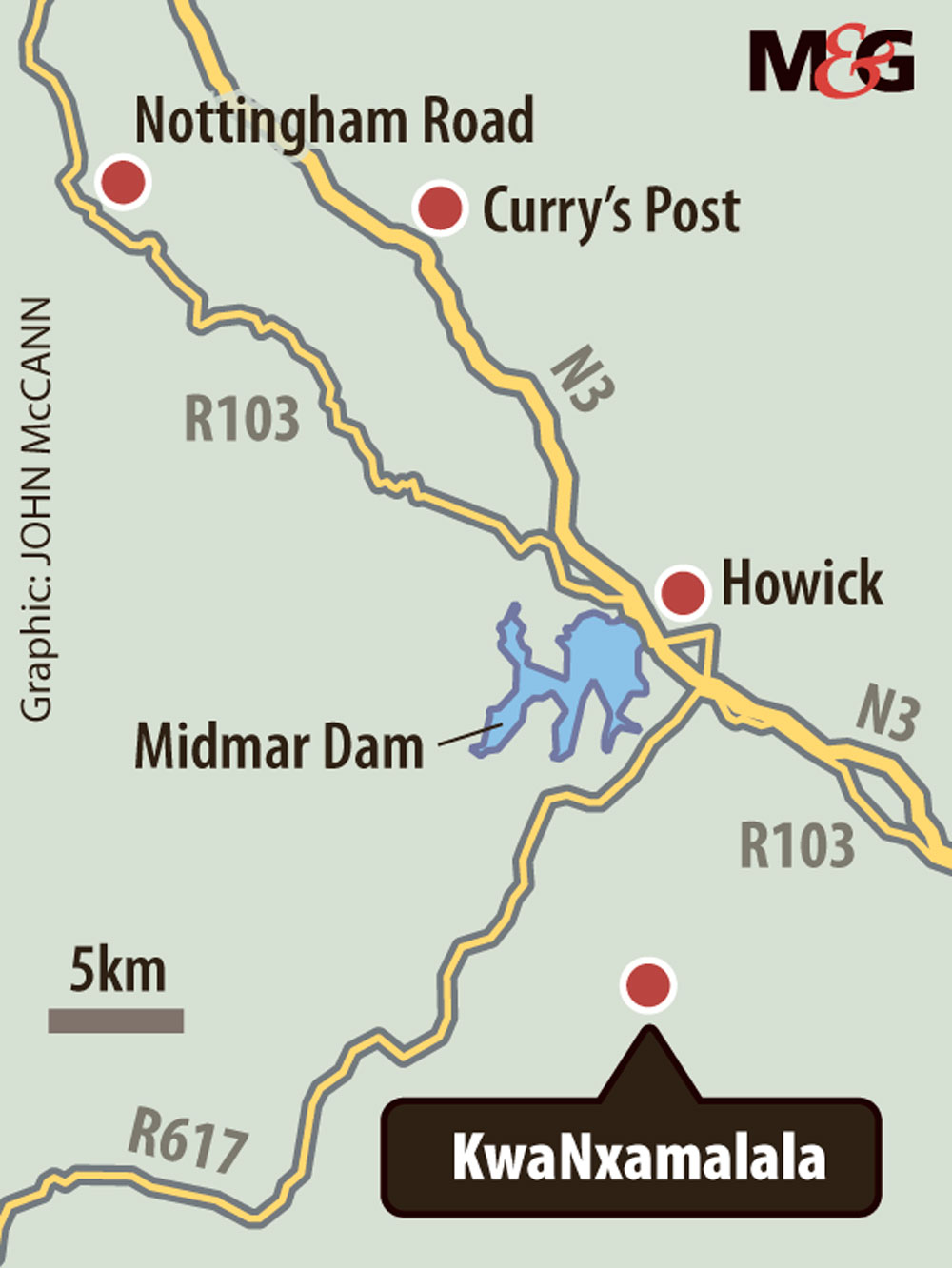

Like many people from KwaNxamalala, near Pietermaritzburg, Bongani Zondi was outside the high court in 2008 when Judge Chris Nicholson handed down the judgment that eventually led to the recall of Thabo Mbeki and paved the way for Jacob Zuma to ascend to the presidency of South Africa.

“There was a picture of me in the Mail & Guardian celebrating, and people were joking that I was in the frontline, his number one supporter,” says Zondi, asking whether we have a copy of the photograph, which he has never seen because very few newspapers make it out here.

Zondi supported Zuma then because he had hoped his life — characterised by casual jobs interrupting long periods of unemployment, stifling boredom and grinding poverty — would change a little. Despite meeting Zuma personally at a public meeting in 2014 and pressing his wish for change, nothing much has happened for him personally.

He is on a year’s contract on a department of public works programme for which he clears road verges and picks up litter for R120 a day. It is a job that puts food on the table but does little for his self-esteem. At the age of 38, Zondi believes it is too late for him to develop a career that will enable him to retire with dignity.

[Bongani Zondi hoped that Jacob Zuma’s election as president would change his life and bring prosperity to KwaNxamalala (Muntu Vilakazi)]

Zondi is not the kind of person who expects handouts: he is inquisitive, opinionated and has a boundless energy for cajoling residents into action or activism.

He believes “knowledge and information are important to hold government officials accountable” for the allocation of tenders and government-created jobs in KwaNxamalala. He asks uncomfortable questions of the local councillor about the provision of basic services, and is a regular face at the municipal offices to chase down annual budgets and integrated development plans to ensure the KwaNxamalala community gets what has been allocated to it.

When the upgrading of a local road meant water supply to households was disrupted, Zondi was, typically, front-and-centre in making enquiries and ensuring tanked water was brought in.

Yet, like millions of black South Africans, he is stuck in penury. Despite the warm greetings of neighbours who stroll past his house and the comradeship he experiences from the Thandanani Hope Group, which was set up by the community’s young people to provide public oversight on government projects in the area, he carries an air of loneliness about him.

He is a maverick in a community that is almost single-minded in its support for the Zuma project — something that Zondi has become less enamoured of because he believes the former president “divided the movement and entrenched factionalism” in the ANC. Although Zondi’s political colours are evident on feet clad in ANC flip-flops, he believes the party is becoming less encouraging of a diversity of opinions and members are “just following what leaders say they must”.

It’s a difficult position to hold in an area that is well populated by the Zuma clan and hardline in its support of the former president. The ANC branch in ward three is named the Gedleyihlekisa branch, after JZ.

The ANC’s Moses Mabhida region, which includes KwaNxamalala and Pietermaritzburg, has been vociferous and hegemonic in its support of Zuma. The former president’s family members run the ANC region and the Msunduzi municipality.

Mthandeni Dlungwane, whose mother is Jacob Zuma’s cousin, is the regional chairperson here. Mzi Zuma, a nephew of Super Zuma, the secretary of the provincial leadership that was judged by the courts to have been illegally constituted, is the regional secretary and another relative of Msholozi. Thobani Zuma, another relative of the former president, is deputy mayor of the local municipality and is from ward three, where Zondi lives.

This hegemony affects all strata of society, according to a local, who, fearful for their safety, asked not to be named: “If you want to get a serious job in the municipality, and I don’t mean being a cleaner or a security guard, but an office job, you have to be a Zuma family member — you must know a Zuma or have their surname.”

The municipality, which was placed under administration in the 2010-2011 financial year, recently admitted that it has gone from having more than R1-billion in reserve to slightly more than R280-million — enough to just about scrape through the next month.

Although the top jobs are affected by “nepotism” — Zuma has made politics a family affair here — the menial jobs are more democratically allocated. Residents interested in the development of a road, the D808, which runs through the ward, put their names into a hat last year before the project began. With 46 jobs available, the first 36 names were drawn from the hat and the last 10 jobs went to households that were identified as most needy at a community meeting with the local councillor.

Zondi and others such as Phumzile Zuma, a single mother of two children, have tried to ensure what is budgeted for ward three is spent on the KwaNxamalala community without any scrimping on quality. But it has been tough.

Contrary to treasury guidelines, the municipality didn’t publish its budget online, which makes getting information and public documents that directly affect their lives from the municipal offices an arduous process, says Zondi. Sometimes “even the officials don’t know where these documents are, and don’t realise that we should have access to them because it enables public participation”.

Residents were in agreement that Linda Madlala was an “approachable councillor who worked well with the community”. But many did express concern about government officials and councillors “feeling threatened” if citizens demonstrated more knowledge about municipal systems and information than they did. “If you ask them about something in the Integrated Development Plan or the budget relating specifically to us, often you get the response: ‘Where did you get that information from?’” says Phumzile Zuma.

Another resident, who did not want to reveal her name for fear of being victimised, said that people were at pains not to disagree with councillors and municipal officials at izimbizo, “because if you appear too clever your view will never be heard again”.

Madlala was recently allocated a personal bodyguard, after the regional leadership became concerned that he may be assassinated because of the ANC regional elective conference, likely to be held in April.

[Some residents in KwaNxamalala work on projects such as the construction of the D8O8 (Muntu Vilakazi)]

Some progress has come to ward three since Zuma became president of the ANC and then the country. More roads have been built and Madlala, who succeeded Thobani Zuma when he moved into City Hall in 2011, says the ward is close to completing its public housing project to build more than 2 700 RDP houses by 2020 — the figure now stands at 2 400 houses completed.

This year, 250 more houses have been connected to electricity and a roads development project, which aims to do away with gravel roads to schools and other public buildings that act as voting stations during elections, will be completed before the national elections next year.

Yet, in many instances this progress provides no succour for poverty’s drudgery. Jobs provided by government are menial ones, which ensure that hope and dignity remain stillborn.

The D808 road, which runs past Zondi’s house, is being upgraded and 24-year-old Cindy Ntuli is working as a labourer on it. She mixes cement, digs holes, lays out pipes but doesn’t believe that this experience will lead to better jobs in the future. For her, the six-month contract, which earns her R180 a day, is reflective of the career ceiling she is resigned to never breaking through.

“I have learnt some skills but this is something that I am doing before I get a real job. I want to be a police, but I have applied and was unsuccessful. I hope I get a real job but sometimes I get stressed because I feel that all I will do is be a flag-carrier.”

This article was produced through the “Accounting for Basic Services: tackling the inadequate use of resources by municipalities and building a rights-based approach to service delivery” journalism project of the Heinrich Böll Foundation, with support from the European Union