Women in Limpopo

The land is not just the dusty earth on which we stand. It is a kinship with our ancestors. It is an affirmation of self. It is the aspiration for dignity and agency. This week Lucas Ledwaba writes about women in Limpopo’s Sekhukhune district who have used the land to improve their lives

The women are taking a lunch break, resting away from the searing Limpopo sun, which beats down fiercely on the land as if bent on punishing those underneath the bare blue sky above.

“It was hard in the beginning. If you saw this land back then you would not believe that one day it would look like this. Some of us lost hope and left,” says Sabina Phala. She is seated among her colleagues under a makeshift shed made from sticks and mealie sacks, which flap noisily in the midday breeze.

The land now comprises neatly cultivated furrows, with newly planted vegetables thriving after a morning of watering.

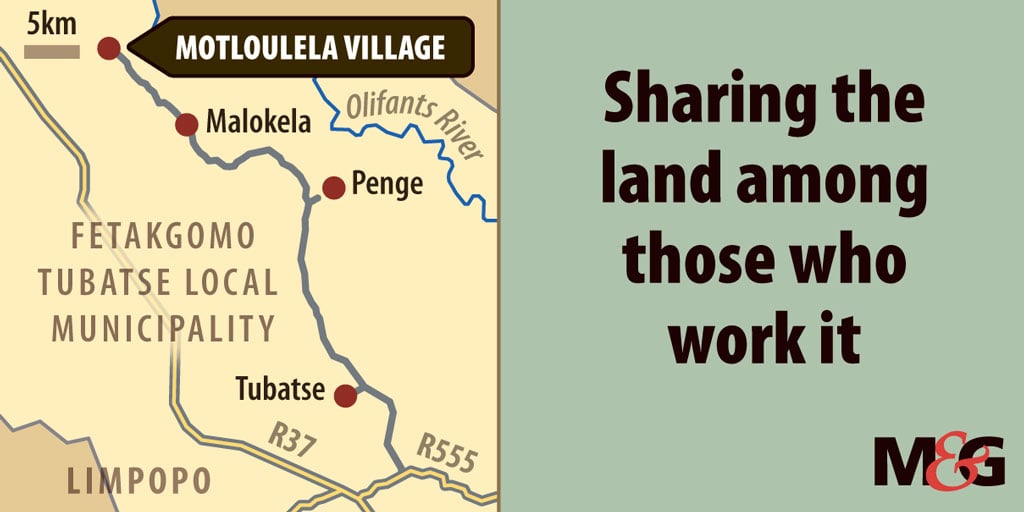

In 2005, women from Motloulela in Limpopo’s Sekhukhune district were struggling to raise their children on the meagre earnings sent home by their spouses or on government social grants. They turned to the only resource available to them — the land.

They had no other resources and no capital, qualifications or sophisticated skills. Many were heading households, with their partners either dead or living far away from home as migrant labourers, earning a pittance.

So they got down to work in the spirit of the celebrated, historic South African Congress Alliance document, the Freedom Charter of 1955, which states: “The land shall be shared among those who work it.”

The group of 63 attacked a two-hectare piece of rugged tribal trust land below the village with pick axes, spades, machetes and hoes. They cleared rocks and uprooted trees with their bare hands.

After almost a year of back-breaking toil, the land was cleared and ready for cultivation. A once-rocky stretch of land, useful only to the goats and donkeys of Motloulela, was transformed. The shiny black rocks and stubborn shepherd’s trees, found in the dry parts of Southern Africa and called the tree of life because of its use to people and animals, that once dotted the land are gone. The soil is a fertile red.

The women then moved into business mode and registered themselves as a co-operative, which they named Motloulela Community Project.

[Women from the Motloulela Community Project break for lunch (above) at their two-hectare farm after spending the morning tending their crops. Sabina Phala (below) is one of the 63 women in the co-operative who work the land for sustenance and an income. (Lucas Ledwaba/Mukurukuru Media)]

“There was too much suffering here in our community. We were really hungry. We used to go up the mountains and cut grass. Then we would go around selling brooms [made from the grass] in town. It was very hard. But as women we had to ensure that our children had something to eat,” says Paulina Kgwedi.

In its 2011 census, Statistics South Africa found that there were 804 people living in 182 households in Motloulela and that 62.1% of the households were headed by women.

The village, 65km north of Burgersfort, is spread out at the foot of a mountain that forms part of the Transvaal Drakensberg range. It is typical of many rural villages in these parts, where residents depend on communal taps for water, there are no tarred roads, erratic cellphone reception and no recreational facilities.

Motloulela forms part of the Fetakgomo Tubatse Municipality, which is the hub of the province’s chrome and platinum mining operations. Although there are mines within a 20km radius, there are none in the village itself, but a small number of the men are employed by some of the mines in the district.

Motloulela is largely a village of the elderly, women and school-going children. Many of the youth abandon the village for the city as soon as they complete matric or drop out of school. Many households are sustained by government social grants, and women are left to find ways to supplement this income.

Away from the comfort of the parliamentary seats where the debate on land reform and restitution continues to rage, the women of the Motloulela Community Project refuse to wait for the lawmakers to deliver to them hectares of land that could make their lives even better.

“We cannot wait for the government. We are the government. We must make things happen because nothing will come easy to us,” says Rebotile Mahlatji.

She explains that those waiting for the land issue to be resolved before taking action will only have themselves to blame for their continued suffering.

The land they farm is tribal trust land. To farm it, they obtained the traditional authority’s permission, but without a title deed as security it is hugely difficult to get a loan to expand their operation.

With the help of a government grant, the project erected a fence around their farm to keep animals out.

They also drilled a borehole and built a storeroom. On a plot of adjacent land, they have built another brick structure, where they can keep up to 200 live chickens. These are sold to hawkers and locals.

There are now 18 women left from the original 63 who started the project. The land is subdivided into separate plots for each of them. They work seven days a week tending to their plots where they plant several crops, from spinach, cabbage and beetroot to butternut, green pepper and tomatoe. Initially they planted maize but abandoned the crop after realising it did not yield good financial returns.

They don’t earn a salary but make money by harvesting and selling their produce to hawkers, who line up next to their farm in bakkies and lorries during the harvest season.

“We have just harvested butternut in December. You should have seen the many cars lined up here,” says Phala.

They also sell their vegetables to households in and around their village and at pension and social grant pay points. Some of the extra produce is donated for funerals.

“We have seen a lot of improvement in our lives. We can feed our families through this land. The land is our wealth. Without it there is no life, we are nothing,” says Mahlatji.

The women hope to acquire more land to allow them to grow even more crops. But they will need to overcome some of their problems, which include being unable to get to the big produce markets. They also want more advanced working tools and an irrigation system.

“The hoe is killing us,” laments Phala.

In Malokela, about 7km away to the southeast, red dust rises from a three-hectare plot of carefully cultivated furrows, where newly planted tomatoes sway in the late-afternoon breeze.

It has been an excruciatingly hot day and members of the Malokela Service Club for the Aged have taken a break to avoid the broiling sun. Some of them return in the late afternoon to check their crops before retiring for the day.

Among them is 85-year-old Kiba Frans Mmola, one of the members who founded the co-operative in 1999.

“We were doing nothing with the land. We would just wait for our pensions. When the money came we would spend it and wait again. That is when we decided to use our land to feed us,” says Mmola.

With the help of officials from the department of social development, about 80 pensioners formed the co-operative. Like the women of Motloulela, they also cleared the land with their bare hands and secured government funding to erect a fence. They each donated R5 and added this to the remainder of their funds to drill a borehole.

The co-operative has a similar model to that of the women of Motloulela. Although many of the original founders have died, their relatives have taken over the portions allocated to them. The project now has 72 members.

“We spend our days here,” says Mmola, explaining that they start work as early as 5am so that they are done by the time the temperature rises higher.

Project chairperson Kgoroba Malatji says they plan to increase the project to 15 hectares and turn it into a fully fledged, commercially viable entity. But because they struggle to get to markets, 5% of their produce goes to waste.

“We can feed ourselves. We can even feed other communities. And if we get access to sell our veggies in the big markets we can do even better than this,” says Malatji.

At its 54th annual conference in December, the ANC resolved to transfer land back to people who live in areas that fall under traditional authorities in a bid to reverse the historical effects of land dispossession.

The ANC’s governance and legislature committee said this was one of the objectives of the Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act, which was passed by Parliament in 2013.

A land audit published by the department of rural development and land reform in November last year revealed that black South Africans own only 1.2% of the land under traditional authorities.

The ANC said during its December conference that it would prioritise training for beneficiaries, who would enter into agreements to ensure the land is worked once it has been transferred.

If the ANC delivers on these promises, projects such as those run by the women of Motloulela and the elders of Molokela could at last use the land as surety to secure loans to help them to expand their operations.

It may also mean that people in such projects would learn how to compete with commercial farmers who sell on the national and regional markets.

Limited business knowledge, which has led to the collapse of a number of agricultural co-operatives and some land reform projects, has led to a perception, especially among white farming organisations and parties opposed to land reform, that land in the hands of black people would be wasted.

Mmola, a retired mineworker, thinks hard and breaks into a smile when I ask what he thinks about these perceptions, which suggest that black people don’t have a plan, the desire or the expertise to work the land.

“The land is ours. It is part of us. When we were born we found our parents working the land. It’s in our blood. We were forced to work for white people so we could get money.” — Mukurukuru Media