Mysterious death: Molly Lubowski testifying before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission about the murder of her son

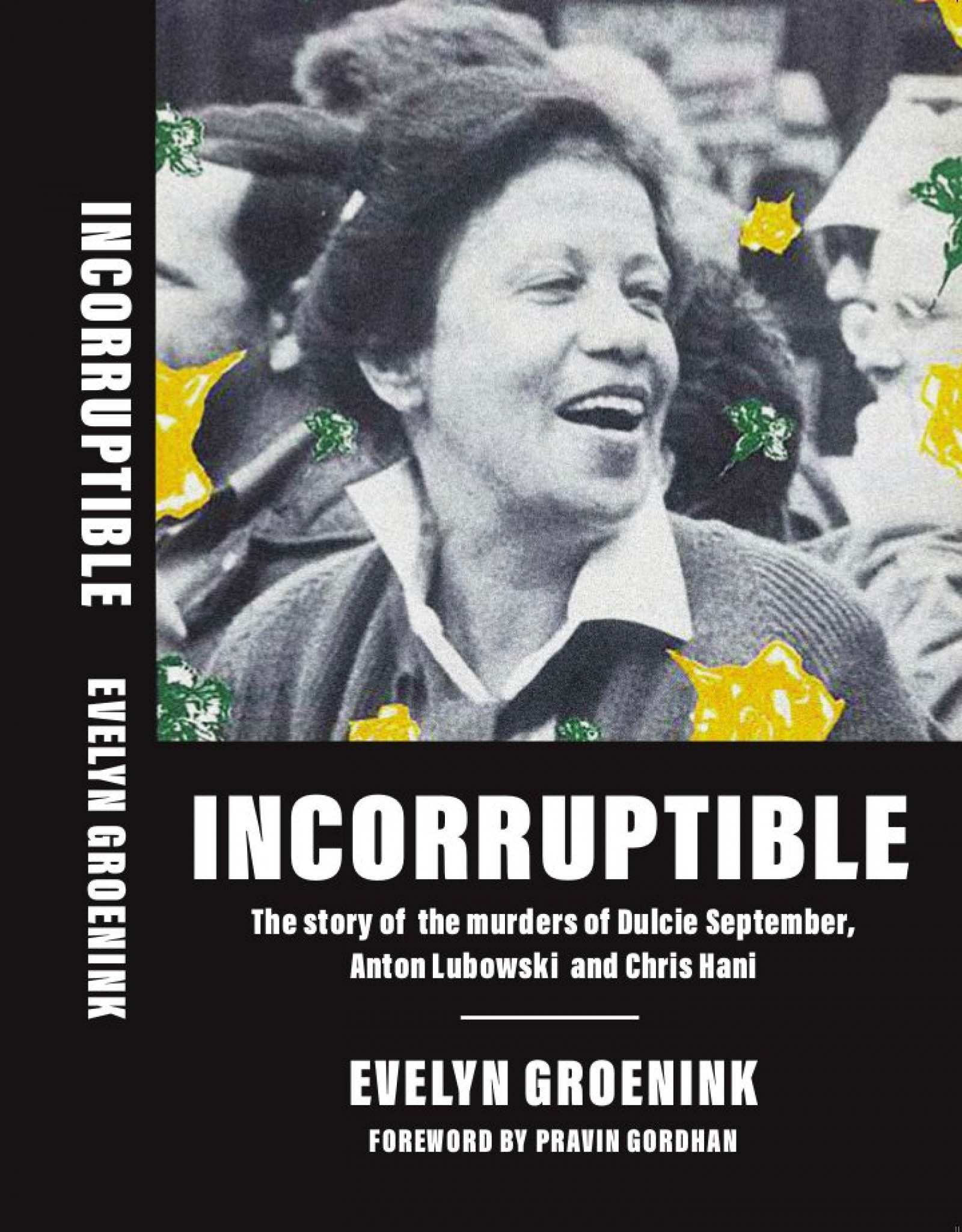

INCORRUPTIBLE: THE STORY OF THE MURDERS OF DULCIE SEPTEMBER, ANTON LUBOWSKI AND CHRIS HANI by Evelyn Groenink (ZAM)

Evelyn Groenink was a dedicated member of the Dutch Anti-Apartheid Movement when, in 1988, the ANC representative in Paris, Dulcie September, was murdered.

September was shot in the face as she entered the ANC’s offices in the Rue des Petites Écuries, into which the ANC delegation had recently moved — and which, as Groenink later discovered, had some odd fellow-occupants. The premises were being repainted at the time, meaning that various painters or pseudo-painters were moving through the building at different times.

At the time of September’s death, rumours of apartheid death squads were floating around Europe, and to many this seemed the obvious explanation. As Groenink works out, however, they were not that credible; such squads had conspicuously left Europe alone in the course of their bloody defence of apartheid, concentrating chiefly on targets in Africa such as Ruth First and Joe Gqabi.

Groenink unravels the implausibilities in the official (French government) version of September’s death, embarking on a search for the truth that has continued for nearly 30 years. Her account includes investigations into the mysterious deaths of “Swapo lawyer” Anton Lebowski in what was then South West Africa in 1990 and South African Communist Party and Umkhonto weSizwe leader Chris Hani in 1993.

Her revelations about Hani’s death are likely to be the most controversial in South Africa, especially because he is still seen as an uncorrupted hero who would have denounced corruption in the new government, particularly the arms deal (announced in 1998 but in the works from much earlier, even before the ANC came to power).

This is part of Groenink’s purpose: she argues that September, Lubowski and Hani died because they were incorruptible — they would have resisted corrupt post-apartheid deals by their own comrades as strongly as they resisted apartheid corruption and the collusion of foreign governments in arming apartheid South Africa.

It will be controversial, too, because there is a very official (you might say canonic) account of Hani’s death, to which the ANC-run government since 1994 has stuck religiously, and Groenink is likely to be accused of peddling conspiracy theories. Except that she finds all the holes in the official version, and they are large holes — witnesses neglected and/or intimidated, as well as factual problems in the testimony that was given credibility by the police. And, for the reader, what might have seemed incredible in 1993 is, after nearly a decade of a Jacob Zuma presidency, not nearly so difficult to believe.

We have also been given, over the past decade or so, a much fuller picture of the global arms trade and the way it operated in Southern Africa — the trade that is, in some way, implicated in all three murders. Books such as The Shadow World by former ANC MP Andrew Feinstein and Apartheid, Guns and Money by Hennie van Vuuren have shown in detail how the arms trade, legal, illegal and somewhere in between, generated all sorts of skullduggery (to put it nicely), of which bribes were perhaps the least criminal.

[Evelyn Groenink’s book argues that Dulcie September, Anton Lubowski and Chris Hani died because they were incorruptible]

Incorruptible is not a straightforward investigative account — it couldn’t be. It is the narrative of Groenink’s own searches, discoveries and conclusions as she uncovers more and more to do with these murders. It is pieced together chronologically, just as Groenink bit by bit pieces together a counter-narrative to the official or part-official stories of who killed whom and why.

Telling it this way, as an autobiographical detective story, is doubtless more effective than it would have been to do it “straight”, even if at first it is frustrating for the reader impatient for hard facts. It becomes an increasingly riveting mystery, with Groenink’s own point of view providing what used to be seen as a fictional technique, a focal consciousness — the thread through the maze.

It also allows for some acutely witnessed storytelling, offering sidelights thrown on the cases by Groenink’s encounters with various figures who were involved in some way or had information to provide (or hide): Aziz Pahad, ANC representative in London at the time of September’s death; ANC veteran Wolfie Kodesh; Solly Smith, a compromised alcoholic and September’s replacement in Paris; September’s family and comrades; Groenink’s own associates and co-workers; a George Smiley-style French agent who secretly helped Groenink, and many others — even Craig Williamson, apartheid’s leading spy and planner of assassinations.

These portraits, however fleeting, add human life and texture to Groenink’s tale, offsetting some of the confusions of the fact-gathering and hole-finding. September, in particular, is portrayed in a way that makes the reader like and admire her, as well as helping to make sense of why some of the French police’s assertions were so misplaced as to hint at a cover-up.

Groenink may have finally published the book she was unable to bring out in South Africa in 2002, overwhelmed as she and the publishers were by legal threats. In that sense there is closure to her long stint of investigative work.

But Incorruptible shows that there is no closure, really, while the truth of these murders remains unacknowledged and the official accounts unquestioned. They are not closed cases, whatever the authorities say; what Groenink discovers means they are still open, still waiting for the whole truth.