Rights and royalties: Dalro head Lazarus Serobe believes that

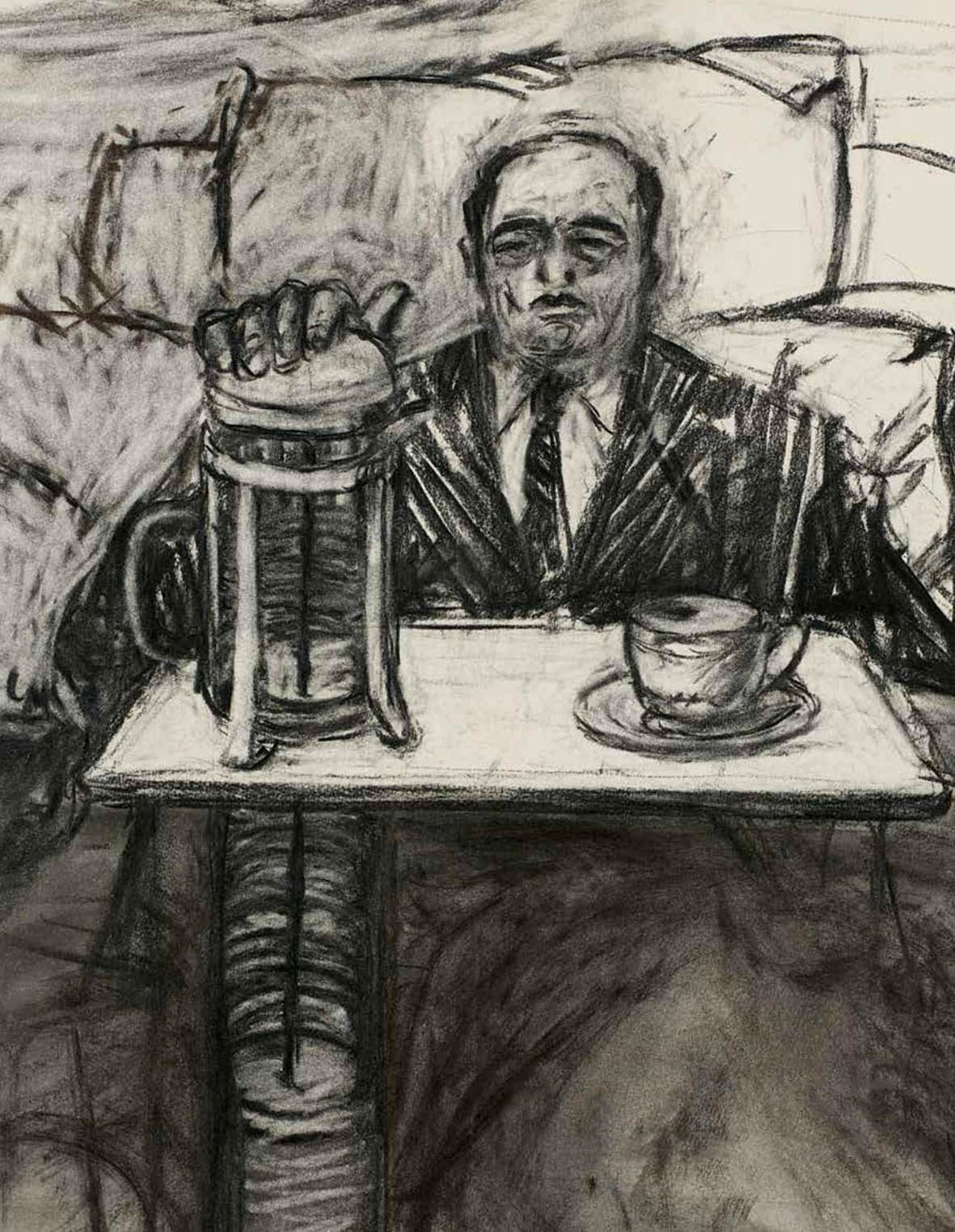

Last year, at a November auction run by Aspire Art Auctions, a 1991 William Kentridge drawing, Drawing from Mine (Soho with Coffee Plunger and Cup), went for an impressive R5.4‑million. In accordance with the company’s practice of offering artists a percentage of the price fetched for their works in the secondary market, Kentridge earned a handsome royalty sum of about R472 500, calculated according to the company’s cumulative sliding scale.

[As per the company’s royalty structure, Aspire Art Auctions sold William Kentridge’s Drawing from the Mine (detail at right) and the artist earned a royalty from the resale.]

James Sey — a director at Aspire Art Auctions, a relative newcomer to the field who made submissions to Parliament as part of a lobby in favour of the artist’s resale right — believes that this is in line with international best practice and could enhance the sustainability of the fine art industry.

An artist’s resale right entitles the creator to a royalty each time the work is resold in the formal market — not only the first time it is sold — and may soon become part of South Africa’s copyright legislation.

“We have done it since the inception of the business in 2016 right up to our fifth live sale, which we have coming up [in Cape Town this weekend],” says Sey.

“Our position has been that we want to be more diverse in our dealings with the market. It is a way of giving back to the artists who are making work, because only at the very top end are they making spectacular money from their work.

“The vast majority are just getting by, so we see it as a way of sustaining the arts industry as a whole. In the two years we have been operating the scheme, we have earned royalties for over 80 artists. Our percentage model is a sliding scale, which is the same percentage model used in Europe.”

According to the auction house’s scale, if a work sells for less than R50 000, the royalties earned are 4%. From R50 000 to R300 000 it is 3%, from R300 000 to R350 000 it is 1%. From R350 000 to R500 000 it is 0.5%. The royalty percentage for resold works that fetch more than R500 000 is 0.25%. The royalties are cumulative.

At the moment, Aspire Art Auctions bears the administrative costs of the scheme but it has recommended, as part of its submission to Parliament on the Copyright Amendment Bill, that a collections agency should take over managing the transactions.

According to documents that form part of its submission, “the droit de suite [French for ‘right to follow’] was first proposed in Europe around 1893 to alleviate the plight of the ‘struggling artist’. Although not yet universal, the artist’s resale right has been implemented in different forms in over 70 countries including France, Australia and Russia.”

The auction house described how the European Union had standardised this legislation in 2001, with the royalty paid through official collecting agencies or directly to the artist. Established auction houses and galleries in the United Kingdom protested against the EU directive, but a decade later the European Commission and the UK Parliament reported that the resale right had not had a negative impact on the art market.

Last year, research by the World Intellectual Property Organisation had backed this up, finding that the payment of royalties on artworks sold at auction had had no discernible impact on prices.

Lazarus Serobe, a lawyer who has extensive experience in the music industry and other creative fields, is the managing director of the Dramatic, Artistic and Literary Rights Organisation (Dalro), a copyright protection agency that has been in existence since 1967.

He begins our interaction by telling me that an Irma Stern painting, Arab in Black, fetched more than R17.5‑million at a UK auction in 2015. But because the artist’s resale right works on reciprocal agreements between countries, Stern’s estate was not able to collect any royalties on her behalf.

In other words, even though the artist’s resale right is in force in the UK, because this right is not law in South Africa, a resale royalty on the work was not due to the estate of the late South African painter.

“It makes a huge difference in an artist’s pocket,” says Lerobe. “When she sold that work for the first time, it probably went for a few thousand rands. For example, France wouldn’t give [the Sekoto estate] a percentage when a Gerard Sekoto is sold, because there, it [also] works on reciprocity.”

Serobe says, at the moment, Dalro represents about 50 South African visual artists, but it is signing more up in anticipation of the artist’s resale right being written into law.

“Our activity so far in terms of visual arts has mostly been around the use of their work in textbooks, so now there is a chance for more activity. But the process has also been to educate the artists — a lot of them are also not aware that it even exists.”

Serobe believes the lobby comes at a fortuitous time, when contemporary African art is experiencing a boom, making international stars of ever-growing numbers of South African artists. “Nandipha Mntambo and Mohau Modisakeng are all artists that are happening. They are being collected profusely, overseas and locally. So the secondary market is going to come,” says Serobe.

“In the mainstream economies, what they call the First World, the art scene has reached saturation; we kind of know what to expect. Art lovers in general — everybody is looking for a new thing, that’s one side of it. On the other hand, African artists have found their voices as well. It goes without saying that the things that are being produced are awe-inspiring. Art fairs are now incomplete without African artists. It’s a situation where we are no longer begging for inclusion.”

Although more countries are adopting it, the artist’s resale right is not yet recognised in huge art markets such as the United States, China and Japan. In France, it emanated from concerns about the financial position of visual artists compared with that of writers and musicians.

According to research submitted by Dalro to Parliament, an artist’s resale right could open up other benefits. “Such regimes can provide other benefits: a means of following the ownership and destinations of artists’ works and providing artists with a continuing link to [them], particularly if the growth of their professional and artistic reputation has led to an enhancement in the resale price.”

Serobe says: “There are a lot of people active in the music space, for example, whereas in the visual arts space, there are very few people independently looking out for the interests of the artists. That has to change.”

The Copyright Alliance, of which Dalro and Aspire are members, is lobbying for artists’ rights to be written into law. There are also visual artists, authors and academic groups on opposing sides, accounting for hundreds of submissions to Parliament.

The trade and industry department-drafted Bill is currently being redrafted by a parliamentary committee, and interest groups are lobbying for it to be finalised this year.