Redemption: On Sunday mornings

Their song is sung with passion and pain. It says: “Bona izwe lakokwethu uxolel’ izono zalo, ungathob’ inqumbo yakho luze luf’ usapho lwakho.” Look upon your nation and forgive its sins. Don’t unleash your wrath and destroy your people.

Perhaps it is sung as an anxious cry to their God, a plea for his divine intervention in a world that persecutes them every day. In the racket and clamour of djembe drums, bells and tiny pillows being beaten with heartfelt passion, they sing: “Lawula, lawula nkosi Yesu koza ngawe ukonwaba, ngezi phithi phithi zethu yonakele imihlaba” — Guide us Jesus because peace will only come through you during these turbulent times on this Earth. They’re admitting that maybe they were too complacent in the continued annihilation of the world they were born into — that, in accepting the abuse, brought to them without protest, they gave their perpetrators absolute power.

But how could they protest when, after all, it is this same God in his black book who teaches them to accept and submit silently?

On Sunday mornings, I observe as my mother carefully beats a small metal rod against her church bell, slowly and carefully, as if each beat is pulsating in her heart. Sometimes she closes her eyes and stops singing to focus on the beat she is creating. I wonder whether it is in these small moments that she is reminded of the tribulations she has faced in the week that was. I wonder whether the songs these women sing afford them the perfect escape from their taxing lives.

These mornings usually begin early, with the voices of ntate Thuso Motaung and moruti Maine viciously waking young souls from slumber with their spirited radio sermons on Lesedi FM.

Breakfast is hastily made: a peanut butter sandwich with rooibos tea, eaten while uMama runs around packing her worn-out Bible and hymnbook into her bag as she makes mental notes of all the items she will need for the service. This is a weekly ritual none of us can ever escape. Finally, we start the short walk to church

Our matriarchs are often treated as peripheral items, the crusts of a human spread that prioritises others. But on Sundays they are important. They are the backbone of the church.

To me, the church sometimes resembles a theatre, and on different days the acts and scenes are played out by the various characters who inhabit the space. They fade in and out as times change.

[Like many black girls, the children photographed, the grooming to find solace in the church starts in one’s tender years for the women (Paul Botes)]

The giggling children who are pretending to listen to umfundisi and hoping not to be scolded by “uGogo weSunday school” for their innocent mischievousness do grow up. The priests come and go, altar ministers retire. The fathers, whose thunderous footsteps would send vibrations beneath the earth as they sang along with oomama, have also faded — many of them stolen by migrant labour and the prospect of city living. Some of them now spend their Sunday mornings singing along to gospel group Amadodana Ase Wesile and Lusanda Spiritual Group at the local shebeen while they reminisce about days gone by.

As the landscape changes there is one character who remains, her position unchanged and her faith unwavering. That character is uMama.

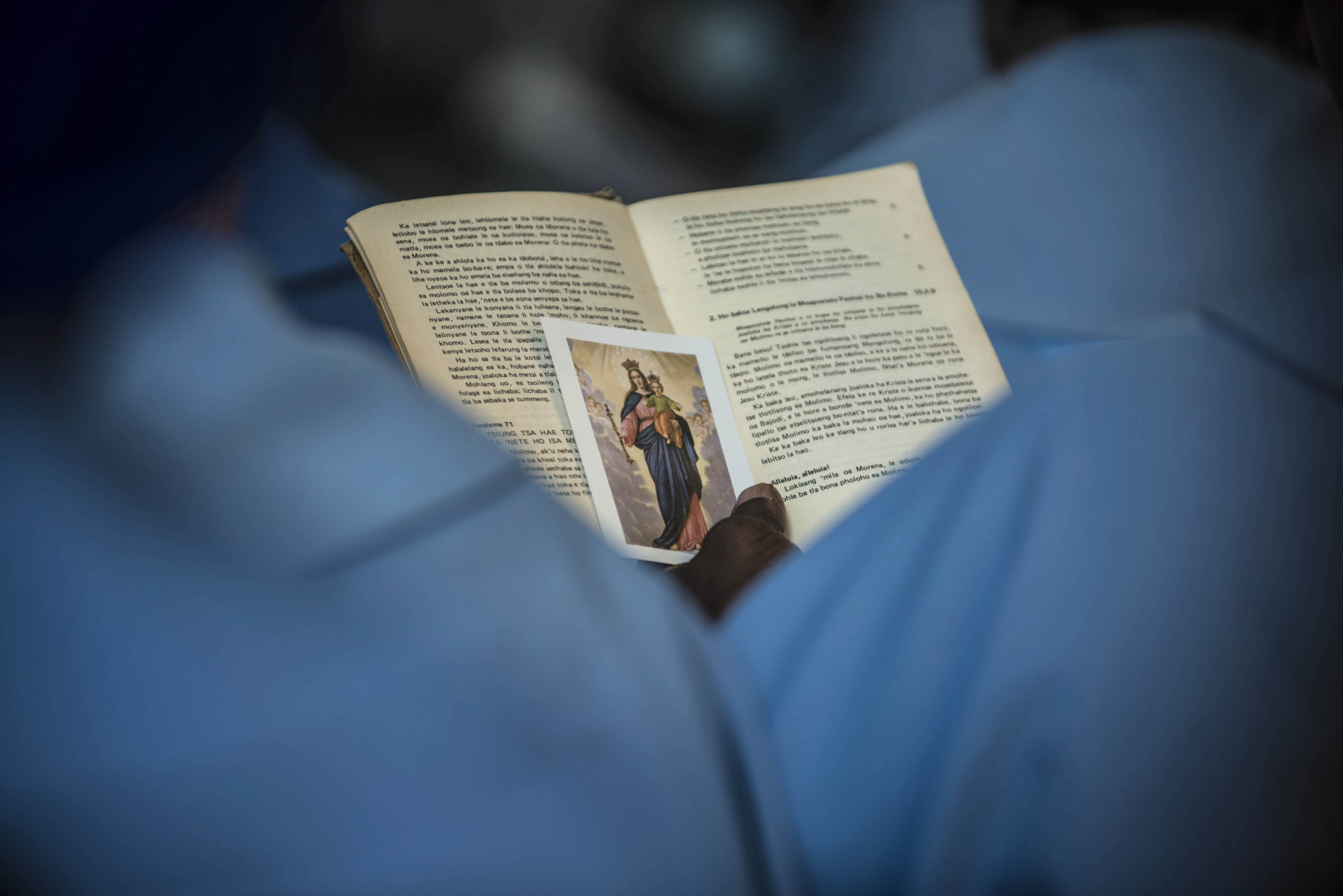

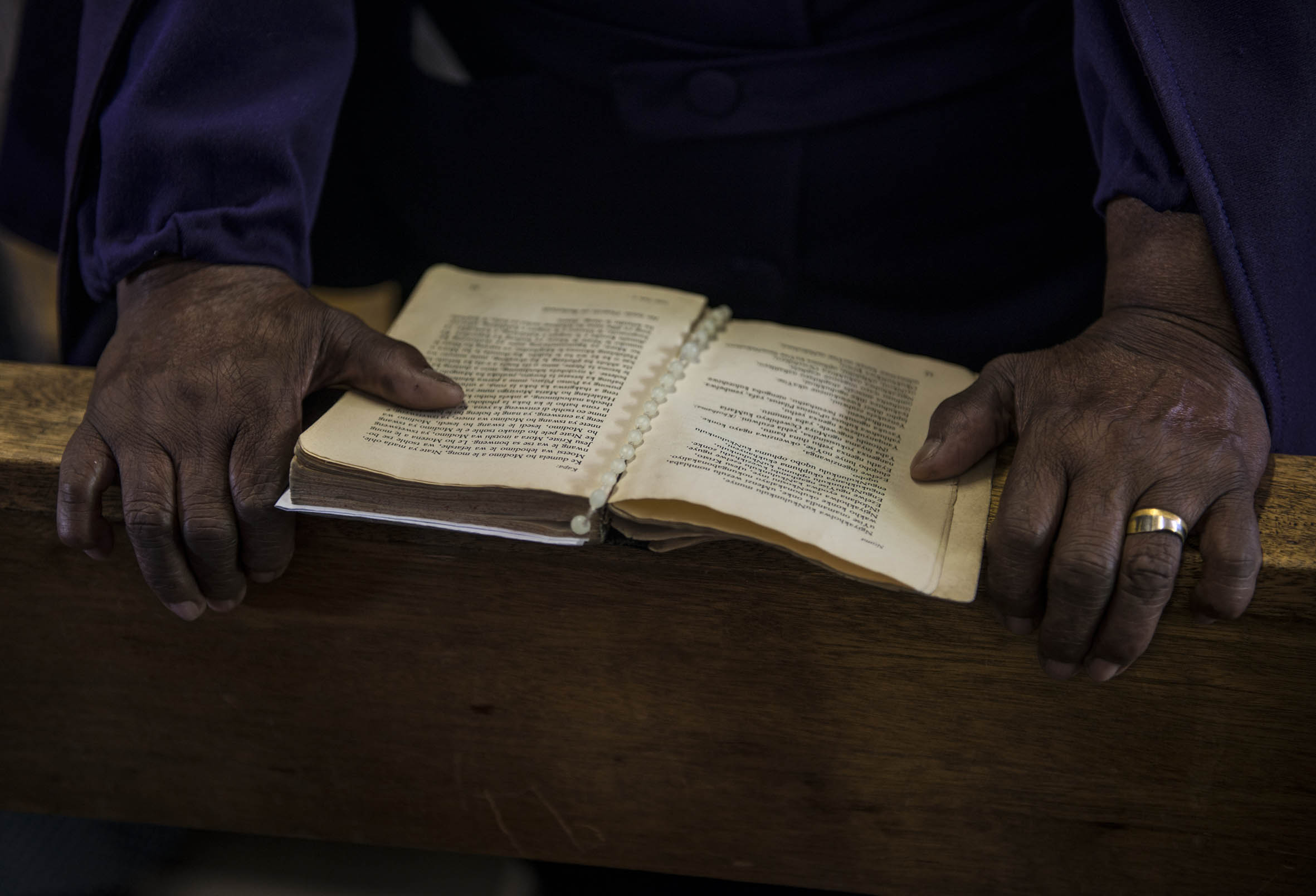

The church remains her saving grace. The words in the small hymn book Difela Tsa Sione give her much- needed solace. She meets other women like her who find a serene sense of bliss in these songs of praise and devotion.

[Difela Tsa Sione provide aboMama with their much needed solace (Paul Botes)]

Sometimes, however, there is great contradiction in this sacred space.

When the priest speaks about women like Jezebel, Eve and Delilah, he speaks with anger and discontent, emphasising their biblical betrayals. He speaks of how Eve cunningly forced Adam into sin by forcing him to eat the forbidden fruit, how Delilah deceived Samson with false love to take away his strength and how Jezebel forced King Ahab to blaspheme and abandon his almighty Yahweh.

In these stories and many others, characters who are so much like uMama are found guilty of committing atrocious crimes against the God she praises in song. None of them are recognised for their devotion and commitment. None of them are commended for remaining resolute in the face of daily adversity.

There is one particularly unsettling story in the Bible. In the Old Testament, in the fourth chapter of the Book of Ruth, Naomi is forced to move back to her hometown after the death of her husband and sons. Naomi, who is Ruth’s mother in-law, is destitute and poor. She asks her daughters-in-law — who have also been widowed — to return to their homes. Of the two, Ruth refuses to listen to her mother-in-law, and chooses rather to stay by her side. Ruth and Naomi struggle to survive but Ruth finds work on the land of a man named Boaz who shows her kindness.

It’s the last part of the story that is disturbing: Naomi — upon realising that Boaz has taken a liking to Ruth — says to her daughter-in-law, “Wash and perfume yourself, and put on your best clothes and go to the threshing floor. Wait until when he is finished eating and drinking and when he lies down, find out where he is lying. Then go and uncover his feet and lie down with him, he will tell you what to do.”

Ruth responds by saying: “I will do whatever you say.”

Naomi is revered and is one of the few women in the Bible favoured by God. But Naomi sent her daughter-in-law to sleep with the rich Boaz so that she, through her daughter-in-law, would become well-off. I’m unable to understand how she could be hailed a hero and a prophet.

[Deliverance: The stories in the Bible about women are mostly of deceivers and betrayers – like Jezebel, Eve and Delilah – yet Naomi is revered for having sent her daughter-in-law to ‘lie down with’ a man in the hope that he’d save them from poverty and insecurity. (Paul Botes)]

As I ponder this story, my thoughts return to my mother, my aunts and the many other black women who have been victims of the pain inflicted by circumstance. The women who have sometimes sat at family meetings urging young women to be silent after their fathers and uncles have raped or hurt them.

I begin to understand where the phrase “Ngezi phithi phithi zethu yonakele imihlaba” — through the troubles we’ve created, we’ve destroyed the world — comes from, and its importance in our world.

I begin to understand that perhaps we need these women and we need their prayers so that we can find a little relief from the dangers that threaten our lives, even the ones in our homes — the ones our mothers are afraid to confront, the ones that cause them to sing with passion and pain when the time comes for praise and worship, for inkonzo ne mvuselelo.