From the weekly prayer meetings to the excitement of wearing her Sunday Best

Mme wa Seapharo (woman of the cloth)

[Women of the African Methodist Episcopal Church wear their uniform with pride (supplied)]

My first church was the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Those Sunday routines were my first spiritual encounters with my first god, Mama.

We’re a little late for church but she keeps her woman-of-the-cloth cool and takes her time finding parking before ushering her five children out of the car, followed by roll call.

Mandla, Nkuli, Frankie, Zaza and five-year-old Zandi.

Our church clothes are inspected to ensure we meet her standards. We wait in line as she uses her hands to iron out her black gown and fix her lipstick. The loose gown has elaborate sleeves and ends below her knees. She straightens up her white collar, held in place by a leopard-print brooch with gold embellishments. Her freshly layered bob flows out of the round leopard hide cap that she wears and sits neatly on her cheeks.

As we walk to the church’s back entrance, Mama’s gold watch and matching ring hand tightly holds my naked 10-year-old wrist. I look up to find her exchanging light cheek kisses with the other women, ba seapharo. From behind her unwavering smile, a greeting emerges. They greet her back: “Dumela Mme Ma Hlalethwa.” Her round face, much bigger than mine, covers the sun so I can only see her silhouette and a halo around her leopard hat. Mama never felt so good.

Food is for saints

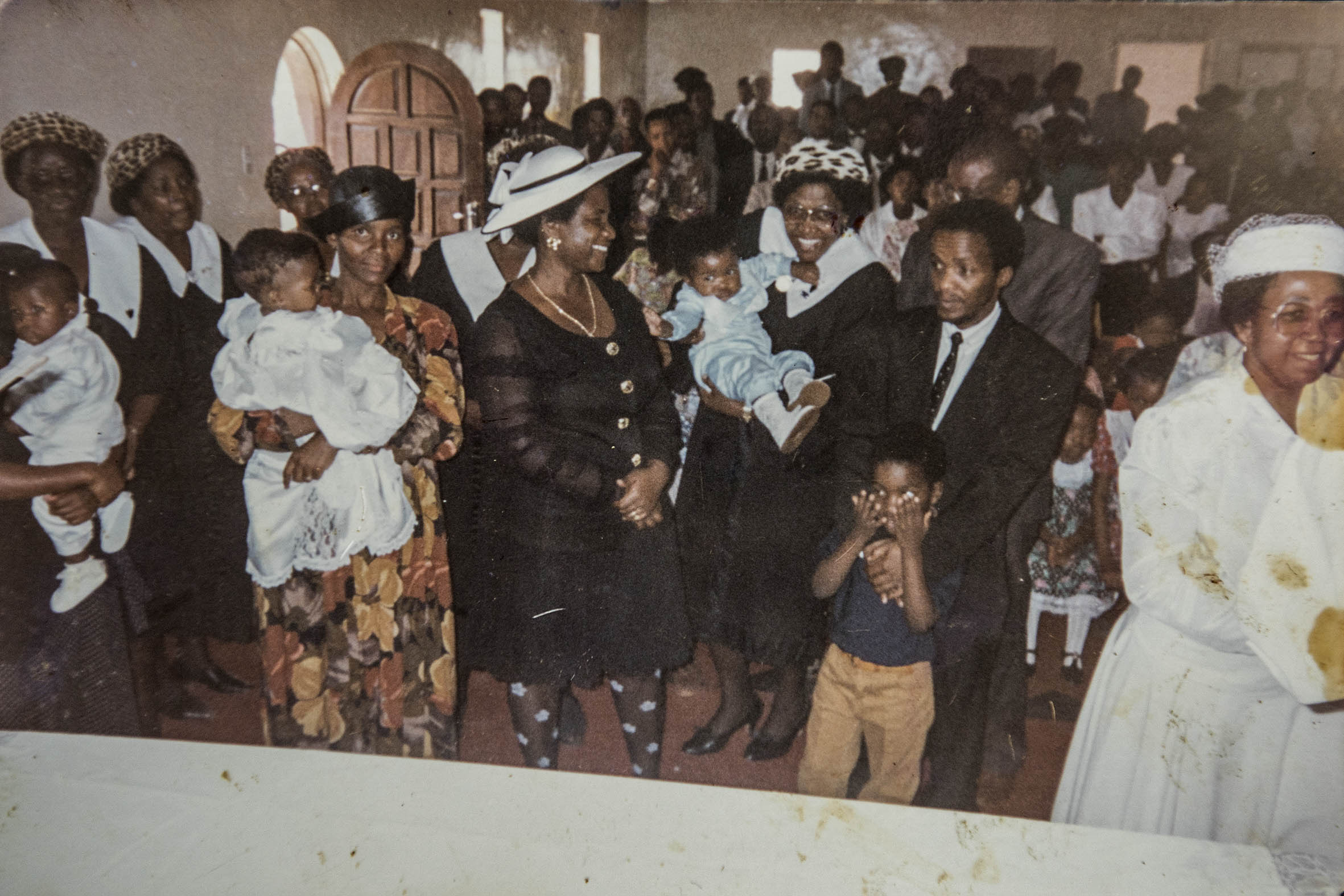

[Growing up with parents in leadership positions in the church caused Zaza and her siblings to be accustomed to proceedings such as baptisms and christenings (supplied)]

Mama inspects the pots of pumpkin, beef stew, green beans with potato mash, yellow rice with multicoloured peppers and a Tupperware filled with grated beetroot salad. She’s in her nude stockings, black two-piece and the five-inch sharp-nose high heels she only wears when she’s preaching. My brothers, in their boxers and pyjama tops, shuffle a set of cards while they watch her in the kitchen.

The three boys have just informed her they are older and no longer want to go to kereke ya molawo (the conventional denominations — Catholic, Methodist, Lutheran, Anglican). Instead of condemning them with her Sunday yelling, which involves her marching between their rooms to pick out their church clothes, she sighs and begins opening and closing each pot on the two stoves in the kitchen.

Mama gives up and decides to fall back on the tradition that raised her. On Sunday mornings Koko Martha, her mother and my grandmother, would lock up her kitchen and leave for church.

“Children old enough to deny the Lord his day are old enough to fend for themselves and do not need my food in my kitchen,” she would say, with her protruding chin raised up high. This was her Sunday law.

Are we done already?

Soft rock music fills up one of Victoria Girls High School’s halls, accompanied by cheerful singing from seemingly sedated smiling faces. Everyone sways from left to right with hands raised high. As we enter, I am dressed in a long, loose floral dress with short sleeves that camouflage last night’s binge drinking, Nike sneakers and my old reliable Bible satchel.

“Morning, welcome to His People church,” says an attendant with the same wide yet sedated smile that comes with matching underwhelming hugs for Oboitshepo and me. We landed up here after my best friend and I, raised on the same Christian values, attended our first-year society sign-up.

There were tents and posters for everything: Wine Society, The Oppidan Press Society, Rowing Club, the BMF Society and the catalyst for our conviction: His People Society.

“The church raised us,” we shrugged. “It’s only right that we try and keep the super-sister-Christian fire burning.” So we set aside our Sunday morning, from 8am to 1pm, for what we thought would be an all-morning long service. Just as we have found a way to bring the clapping and stomping church feeling we were raised with to the Praise and Worship playlist, the preaching begins and is followed by a short closing prayer before we have even settled into our seats. Haow. Oboitshepo looks down at her watch and mouths: “It’s only been 45 minutes,” as we get up and assemble around the white church’s traditional post-church tea and biscuits table.

Cash Rules Everything Around Me

I jump out of bed when I realise it is 9am and my mother has not condemned me out of bed to get ready for church. The halls of the house are not filled with Thami Ngobeni’s Metro FM Sunday morning show, coming from my mother’s hand-held radio or smartphone. The halls are as dark as they are on a Saturday morning when no one is obligated to wake up early.

Mama must be sick, so I head to her room to find her and my dad sitting up in their bed that is this morning decorated with various Bibles: the old reliable NIV, the Amplified Version, The Message Bible and the Setswana Bible, famous for the pink perimeters of its pages.

“I am taking a break from the church,” Mama sighs. Although the words I hear sound and look as if they have come out of Mama’s mouth, it takes a while to register. Mama is fatigued from fighting corrupt church councils and flashy pastors who let church members with fat tithes and offerings rule the day.

She orders me to prepare a pot of oats, wake my siblings and dish up for the seven of us before we congregate in the living area, armed with charged phones with screens displaying our preferred Bible apps.

“From now on, this will be our church. We will pray here, sing here and share the word. We don’t need a building where they pretend to do this purely because the Word says: ‘Where two or more are gathered in my name, I am there with them.’ Modimo onale rona. My God will not forsake this family,” she says, paging through her Sellotape-covered Bible.

God is my alibi

Going to Catholic schools is a Hlalethwa family tradition. My father and his siblings attended Holy Trinity and CBC Mount Edmund. So my siblings and I went to Loreto Queenswood, Assumption Convent and I ended up at Iona Convent School for Girls. My school career was built on the foundation of routine religious practice. There was a time, place and manner in which we would commune with God: Mass, religious education, prayers before and after lunch and prayer books that instructed us on what to say, verbatim.

The noon bell gongs as we take out Mrs Richardson’s long division homework. I sigh with relief as Tumi whispers an excuse into our militant maths teacher’s ear and signals to the class that we take out our prayer books. All 25 11-year-olds stand and page to the Angelus prayer of the cream booklet with black microscopic writing.

Tumi nods and we recite the prayer. It contains several Hail Marys among other prayers that I failed to memorise in order to remember twelve years later. We became the Grade Five class infamous for reciting the Angelus in a snail-paced monotone that ate into Mrs Richardson’s time to inspect our maths homework on Tuesdays. God was on our side.

These encounters, each joyous in its own way, sit incongruously with the discomfort I face when I walk into church now — as a preacher’s kid, no less — and complicate what churching has come to mean to me. Is it the meeting place? The people? The idea of God? The rituals and the uniforms, or the prayers?

But while I question the intricacies of Christian fellowship and their consequences for my own spiritual agency, I cannot help but celebrate them with a cheerful shrug and a smile. I belong.