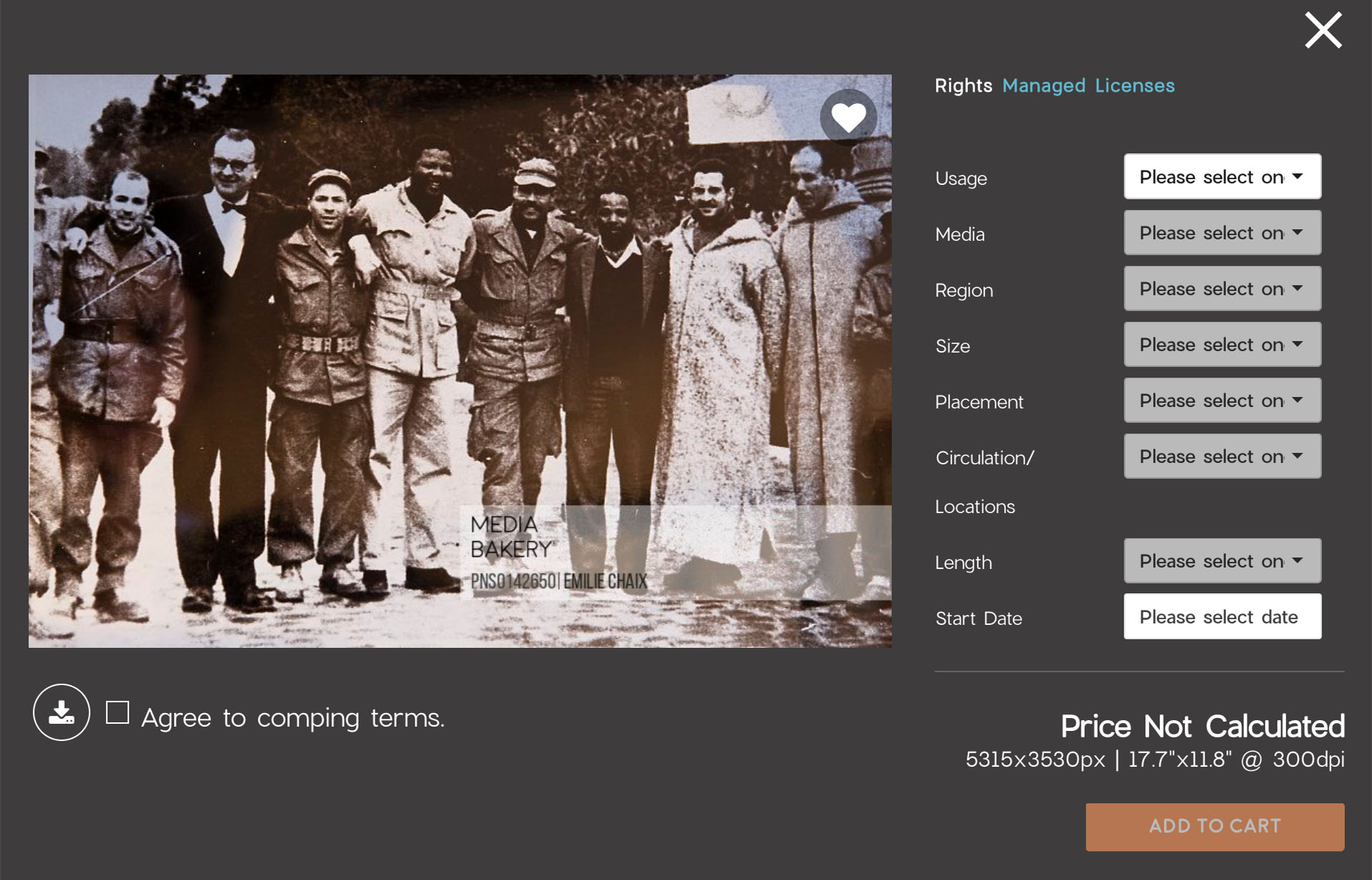

History for sale: Images such as these of Winnie and Nelson Mandela

The greatest photographer of South Africa’s contemporary history was there at the Treason Trial in 1956. She was there again in Algeria with Nelson Mandela, and with Winnie Madikizela-Mandela in the 1960s. And, of course, she captured the killing of Hector Pieterson in 1976.

Except French photographer Emilie Chaix was never there.

Chaix supposedly travelled from Vilakazi Street in Soweto to Algeria to take iconic photographs that have been wrongly credited to her the world over.

She’s not the only imposter: the legacies of photographers such as Alf Kumalo, Peter Magubane and Sam Nzima have been plundered, wittingly or unwittingly, by reputable agencies such as Gallo, Getty and AFP, and publications like the Sunday Times.

The piracy of era-defining images taken by black South African photographers is once again in the spotlight following the death of Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, which has resulted in a spike in the unauthorised use of photos captured by the select few photographers who were given access to the Mandelas’ lives.

Madikizela-Mandela’s death has also laid bare a roaring international trade in counterfeit photographs implicating both rogue merchants and reputable agents.

Chaix’s images are distributed by photo agency Photononstop, which licenses them to news agency AFP for distribution. But they are not alone in peddling iconic South African photographs that are not their own.

On April 11, the Mail & Guardian contacted Blaine Harrington III, a photographer in Littleton, Colorado, in the United States, who was ready to sell a Kumalo image of Mandela playing with his pet dog at his Orlando West home.

The M&G posed as a Southern African blogger who could not access the rights to the original because of the shambolic state of Kumalo’s estate. Harrington, who acknowledged in a taped phone conversation that he would be selling us a “picture of a picture”, was willing to forego the higher prices demanded by his agent alamy.com, and charge $55.

“My fee would be $50 USD plus $5 to cover PayPal, so total $55 USD. That’s the best I can do, otherwise I have to pass. If you want to do it, you need to pay me by PayPal right away so I can email back a digital file immediately. I’d need to know the size you want the photo. I’m here for the next 1½ hours if you want to proceed.”

On his website, Harrington offers a stern warning to anyone who infringes on his copyright, saying the offender will be charged a “triple fee for unauthorised usage and/or prosecuted for copyright infringement”.

The M&G also tracked down Chaix, whose modus operandi seems to be to travel to the world’s museums and return to France to pursue a roaring trade in hawking memorabilia and historical photographs. Her work is seemingly licensed primarily through Photononstop but also appears on websites such as diomedia.com and mediabakery.com.

Chaix dropped the phone and it remained switched off for the rest of the day as soon as she established that the call was from South Africa.

Photononstop’s sales manager for France, Veronique Therme, was apologetic when contacted about the rights to distribute the images. The images captured on media-bakery.com, a partner agency of Photononstop, include the one of Mandela and his dog, images by Magubane, as well as, quite brazenly, Nzima’s unmistakable photograph of a dying Hector Pieterson.

“I saw those images,” said Therme. “I don’t know. I suppose it is an error. We saw it; when we were informed, we withdrew the images. None of them are there any more. We do not do business like that. She [Chaix] took images she was not allowed to take and we don’t check [the veracity of] all those images.”

Photononstop was tipped off by AFP, which, as a partner agency, had carried some of the images on its website.

In the April 8 edition of the Sunday Times, Magubane’s arresting images of Madikizela-Mandela — one capturing her braveness amid the desolation of Brandfort and another suggesting the toll the struggle years had taken on her — were used prominently. One was credited to Magubane, Avusa, Gallo Images and Getty Images. The other, which has come to be associated with the Pascale Lamche-directed Winnie documentary, appears to be a rip-off of an existing Magubane image, with incriminating creases and folds striating Mam’ Winnie’s visage.

When visited at his Melville home, a frail Magubane was resolute about what he considered his unfair treatment at the hands of the South African media. “I don’t know why, here in South Africa, it is done that openly,” he said. “There have been times when pictures were published without my permission and I took it up with them. But these people don’t listen, you see. South African newspapers do not respect copyright.”

Copyright lawyer Buhle Lekokotla, of the Victoria Mxenge Group of Advocates, said a genuine lack of knowledge about who the copyright owner or author of an image is could account for their flagrant misuse.

“This is mainly exacerbated by the fact that, unlike all other intellectual property rights, copyright does not need to be registered, except in the case of cinematograph films. So, unless the photographer states specifically that they own copyright, people are unlikely to know who the owner or author of copyright is.”

Lekokotla said, however, that “lack of knowledge is no excuse in law, as long as the owner of copyright can show that [a person or company] knowingly used the photo without authorisation or without crediting the owner”.

Sunday Times acting picture editor Nolo Moima said that the photos by Magubane, in particular, had been used under the assumption that the paper held the rights to the images because he had worked there. The newspaper has since arranged to meet Magubane.

David Meyer-Gollan, Magubane’s aide, said publications such as Drum, where Magubane had worked between 1954 and 1963, respected his rights to his pictures. But according to photographer Omar Badsha, that did not come without a fight, which was spearheaded by Jürgen Schadeberg. The former Drum photographer’s court battle let him wrest ownership of his images from Bailey’s Archives and had a positive ripple effect on several of his colleagues.

Badsha says that, morally, publications are obliged to pay to use the images but, legally, Magubane must prove that the pictures are his.

Establishing the ownership rights for Kumalo’s pictures, which have also been widely circulated and reproduced by the Sunday Times and international agencies, is complicated considering the dysfunctional nature of his estate.

“Due process must happen, and that needs full-on consultation,” said Mzi Kumalo, who was tasked by his father with managing his now-decrepit Soweto-based photographic museum. “I don’t think it can belong to us as a family. It belongs to South Africa. For me, the ideal scenario would be if a university took it on as a project.”

The younger Kumalo did not know how specific Madikizela-Mandela photographs, purported to be taken by his father, had ended up uncredited in the hands of Gallo and other distributors.

Responding to an inquiry about the rights to the Brandfort image of Madikizela-Mandela, Gallo Images chief operating officer Herman Trollip said the company distributed all its content “under agreement from its contributors”. Magubane denied he had given Gallo the right to use his images.