Come 2019

POLITICS

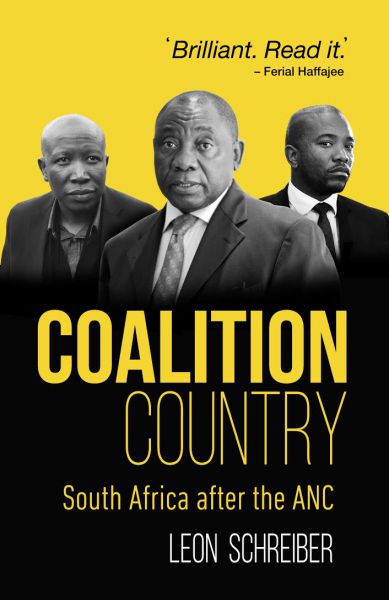

Based on the experiences of other coalition-based societies, the section in my book, Coalition Country, titled Three Futures, introduces three scenarios of what it could mean in practice when coalitions become the norm in South Africa, although they are not the only possibilities.

By definition, one of the core features of coalition-based polities is that they are much more unpredictable than countries dominated by only one or two political parties. It is plainly impossible to envisage all the different potential permutations that await South Africa.

Looking across the country’s 226 local municipalities, 44 district municipalities, eight metropolitan municipalities and nine provinces, it is likely that there will soon be dozens of different political combinations in charge of local, municipal and national governments. As politics becomes more competitive, the influence of independent candidates, especially in municipalities, will become yet another important factor that introduces even more uncertainty.

It goes far beyond the scope of this book to examine every possible coalition combination across South Africa’s 288 different elected governments (278 municipalities, nine provinces and one national). Instead, we will stick to the national level, with each of the scenarios only briefly touching on some of the potential effects at the subnational level. (If the ANC does indeed lose Gauteng in 2019, the quest to build a coalition government in that province will be the most vivid example of how the challenges outlined in the three national-level scenarios are also relevant to the provinces and municipalities.)

Even if we largely focus on the national level, predicting how a government will be constituted is about to get exponentially more complex. Previously, as soon as national election results were announced, South Africans immediately knew who their next president would be. But, once the ANC vote drops below 50%, citizens will need to wait for up to 30 days to find out who will become the next president (the Constitution allows up to 30 days for the National Assembly to elect one of its members as president).

The 30 days following the 2019 election could be one of the most decisive periods since 1994. With ANC support below 50%, political parties would need to use these 30 days to cobble together a coalition to take over the national government. Based on the electoral trends outlined in part one of this book, there would likely be only three potentially realistic outcomes.

In the first scenario, the Democratic Alliance and the Economic Freedom Fighters (and potentially one or two smaller parties, including an ANC breakaway) establish a coalition that leaves the ANC out of power.

In the second, the ANC and the EFF (maybe with one or two smaller parties) build a coalition that leaves the DA out of power.

In the third, the disagreements among parties are so stark that they are unable to work together to create a formal alliance. Instead, political leaders haggle over each and every decision, including the election of the president.

It is also important to explain briefly why a fourth scenario that is theoretically possible — that of an ANC-DA coalition — will not happen.

There is no rule that prevents the ANC and the DA from establishing a “grand coalition” after 2019. Indeed, many countries, notably Germany, regularly feature coalition governments that include the two biggest parties. Politically, the strongest argument in favour of such an arrangement is that it usually accommodates a large majority of voters. This gives such grand coalitions a high degree of legitimacy.

South Africa may in fact feature a grand coalition at some point during the 2020s. For example, if the ANC’s fall in 2019 is the motivation it needs to finally reform itself from a liberation movement into a modern political party, we might even see a DA-ANC grand coalition as early as 2024.

But given the country’s current political atmosphere — in which the ANC is fundamentally tainted by corruption and maladministration, and part of the DA’s raison d’être is to prove that it can out-govern the ANC — it is near impossible that the DA would risk entering into an alliance with the ANC in the short term. We can safely disregard the possibility of an ANC-DA coalition in 2019.

This leaves us with the three scenarios outlined above. The first, in which DA and EFF leaders muster the maturity needed to keep a diverse alliance together, holds the greatest short-term promise for fixing South Africa. The second, in which the EFF “returns” to the ANC in a a post-2019 coalition, unleashes the populist demons that have long barked at the gates of South Africa’s democracy. In the third scenario, in which neither the ANC, the DA nor the EFF is able to form a coalition in 2019, South Africa in effect grinds to a halt under the weight of political deadlock.

There is nothing deterministic about these three scenarios. Instead, each is based on certain probabilities. The weight of probability does not guarantee that a DA-EFF or an ANC-EFF coalition will not become deadlocked and paralysed. Nor does it mean that a DA-EFF coalition will be insulated against populism and corruption, or that an ANC-EFF alliance can never enact pragmatic policy solutions.

What probability does mean is that, based on the evidence that has accumulated in the build-up to 2019, a DA-EFF alliance is most likely to undertake the deep structural reforms the country needs.

In turn, of the three options, an ANC-EFF coalition is most likely to deepen the populist and corrupt practices that have already brought South Africa to its knees.

Finally, a minority government is most likely to be mired in incessant infighting. In the coalition era, there will be even less certainty about what the future may hold. But that does not preclude us from weighing up the evidence to make informed forecasts about what each possible future is likely to look like.

By examining the different parties’ policy documents and election manifestos, the next section explores what different coalition configurations could mean for government policy on some of the most hotly contested issues in South African society, including land reform, education, economic policy and civil service reform.

More than anything else, the goal behind these three scenarios is to motivate readers to start thinking through the likely implications of different political coalitions at the national level, but also in their own provinces and municipalities.

The three scenarios are not intended to be the final word. Rather, the goal is to use them to start an ongoing conversation about coalitions, which will soon become the way in which South Africa is governed.

This is an edited extract from Coalition Country by Leon Schreiber (Tafelberg) . Schreiber is senior research specialist at Princeton University in the United States