Nkhetheni Nevhutanda

The land is more than just the dusty earth on which we stand. We grow from the soil and we go back to it. This week Lucas Ledwaba writes about a few dedicated souls who are leading the fight to restore the spiritual relationship between the land and its people

In another time the area around the Phiphidi waterfall was a zwifho, a sacred space. Only a few select members from a lineage of healers in the Ramunangi clan of the VhaVenda were allowed to meet there to perform rites to summon and give thanks for the rains.

The waterfall is surrounded by towering forest trees that poke into the sky like antennae of the gods. The water in the Mutshindudi River tumbles about 20m into a large pool hidden in a natural amphitheatre of indigenous rainforest.

In the early morning the area is often hidden under a blanket of mist. Sun rays pierce through the gaps between the branches, giving the falls a mystical aura associated with its reputation as home to the swirling spirits of the gods and the mythical lion that roared to summon the rains.

But the wise ones from the Ramunangi go there no more. They have not been for a while. It is possible they may never return there. Those in the know say even the mythical lion, Guvhuguvhu, whose roar once haunted this holy site, has gone silent.

What can be heard now is the easygoing chatter of tourists. The area is a resort with a lodge, where R20 gives you access to the waterfall and R300 secures you a night in one of the chalets built above the falls.

Along the banks of the lazily flowing river are braai stands, around which visitors quaff beverages in the cool shade of the dense forest.

It is just another holy site caught up in the never-ending, protracted battle between preserving tradition and using nature for commercial gain. Its amazing beauty has not escaped the eye of developers.

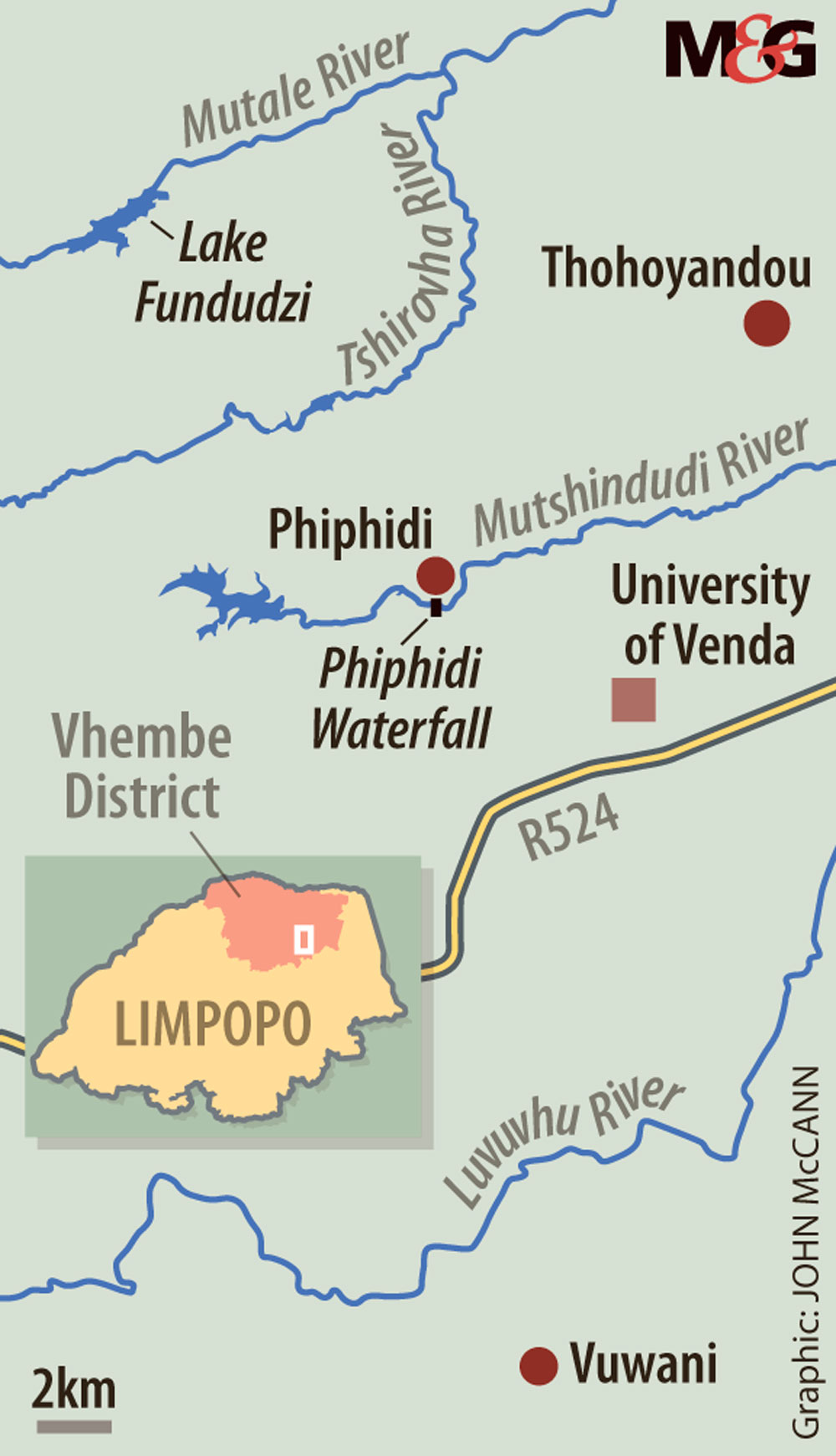

The falls form part of the Sacred Lake Fundudzi Heritage Hub, which makes up the Greater Mapungubwe Heritage Route. The route, in the Vhembe district in the far northern part of Limpopo, includes other Venda holy sites, such as the Tswime Breathing Stone, Lake Fundudzi, Miyohe Sacred Hill and the Makonde Cave.

[Nkhetheni Nevhutanda is a member of Dzomo la Mupo, which means ‘to speak for the natural world’. The organisation is working to protect Venda’s sacred sites, such as the Phiphidi waterfall, and prevent mining in ecologically sensitive areas. (Lucas Ledwaba/Mukurukuru Media)]

The theme of consecrated space and myth is a powerful selling point for those in tourism marketing but it causes much pain and outrage to those such as Mphatheleni Makaulule, who regard it as a cheap marketing gimmick.

“All these sacred sites are vulnerable to the greed of men. How do you destroy a whole ecosystem to build a hotel? When they [developers] see a river, they just want to block it. They see a forest, they want to log. Human beings are destroying their own habitat,” Makaulule charges.

Venda is a picturesque part of Limpopo, a land of great hills, forests, rivers, waterfalls and lakes, whose beauty soothes the soul. But behind the beauty of the hills and gorges lies a deep spiritual meaning that binds the people to the land.

Tradition dictates that some of these hills should not be open to everyone, that some of the rivers and lakes should not be swum in and that some spots are so sacred that it is taboo to point at or photograph them. These are the zwifho. To the Venda people, the land is not only a source of food but also a revered holy of holies to which they are bound spiritually, for it is a gift from the gods.

Makaulule leads an organisation called Dzomo la Mupo, a mouthpiece for nature. Its mission is to protect nature in its entirety, to give it a voice against the destructive hand of people and to preserve the planet for the benefit of all humankind.

Mupo can be superficially translated as nature, though it has a much deeper meaning.

“Everything which is not made by man is mupo. Sunlight, moonlight, rivers, waterfalls,” says Makaulule.

[The Phiphidi waterfall is one of Venda’s sacred sites. But it has been ‘developed’ into a tourist attraction and resort, despite a court interdict. Mphatheleni Makaulule (below) is campaigning to preserve the numerous sacred sites, indigenous forests and nature in general through her organisation Dzomo la Mupo. (Lucas Ledwaba/Mukurukuru Media)]

As part of its programmes, Dzomo la Mupo works with teachers and students to revive cultural biodiversity, and is also working with people living in the area to preserve certain seeds such as finger millet, maize, beans and sesame.

One of their main projects is to protect sacred sites and natural forests in the Vhembe area of Venda.

“We pay more attention to sacred sites because they are everything to us. They connect the sun, moon and Earth. Sacred sites hold the harmony of the universe. They are keepers of people. They hold the spiritual, ecological and social connection between us and the universe. Sacred sites are our connection to God, to the land,” she says.

Makaulule is studying for a master’s in indigenous knowledge systems at the University of Venda in Thohoyandou. She is researching the significance of pumpkins in Venda society. Although it is generally known to be a nutritious vegetable, in Venda and Bantu cultures it holds more meaning, including being a symbol of fertility and reproduction.

She has received international awards for her activism. Her work with Dzomo la Mupo has taken her to meet indigenous communities in places such as the Amazon, Ethiopia and Kenya to share ideas on how to protect Mother Nature and their heritage.

Makaulule says there are at least 49 known sacred sites in Venda, although there could be many more. But, for now, they are fighting for the preservation of those that have been identified.

One is about 1km from her home in Vuwani, a hill known as Vuu, where, for hundreds of years until the late 1800s, the Ngona people smelted iron.

Makaulule’s husband, Dr Mashudu Dima, a Venda cultural and historical expert, says the Ngona people, who trace their origin to this area, fashioned farming implements, artefacts and weapons from a stone known as mbwedi.

The area became a significant trading centre supplying people from the kingdoms of Mapungubwe and Sofala (in modern Mozambique). It is believed that the Zulu king, Shaka, sent emissaries to Vuu to have an iklwa — a short spear — fashioned by the Ngona.

[On Vuu hill near Makaulule’s home in Vuwani, the Ngona people smelted iron for hundreds of years. A pipe was used during the process of melting the metal out of the ore. A section of the hill is sacred. (Lucas Ledwaba/Mukurukuru Media)]

Dima says the hill got its name from the sound of bellows, made from goat or cow skins, which were used to fan the flames of the smelters’ fires. In turn, the hill gave its name to the town of Vuwani.

The smelting site below the hill is accessible to the public but the sacred area on Vuu hill is not. Only diviners from the royal family may go to the hill to conduct rites.

“It is our heritage site,” says Matamela Ramathithi, chief of Vuwani.

Locals hold Vuu in awe and speak of nights when hypnotic drumming and singing resonate from the hill.

Ramathithi, whose homestead is on the path to the summit, says he has been woken by musical notes coming from the hill. “It happens many times,” he says.

In 2010, Dzomo la Mupo went to court and successfully interdicted the Tshivhase Development Foundation Trust from developing the resort around the Phiphidi waterfall. But the development went on regardless.

In 2013, it lodged an objection to the application by Coal of Africa Ltd to be granted a water-use licence for the Makhado coal mine, arguing that, if mining in the area goes ahead, it would lead to severe damage of sacred sites and would have dire ecological, social and economic consequences.

Makaulule is softly spoken, until she begins to talk about her life’s passion. Then her deferential manner gives way to a spirited outburst, her love for the land and Mother Nature shooting from every word as she speaks.

“Used condoms! People sleep and do all those dirty things at the zwifho. Just imagine,” she says of the resort now operating around the Phiphidi waterfall.

Makaulule says, to the Venda people, and Africans in general, to destroy Mother Nature is to wage war on the gods. And to wage war on the gods is to invite their and Mother Nature’s wrath.

“If you disturb mupo, it will fight back. What are the real causes of global warming? What causes climate change?

“We are destroying the land in the name of economic development. It [economic development] is the biggest contributor to the destruction of mupo,” she says.

In recent years calls for the return of the land have been coming especially from young people. But Makaulule says there is “a gap where young people don’t understand the true meaning of land”.

“Young people have been disconnected from the indigenous way; they have been made to believe that land is only this five hectares you can cultivate. It is more than that,” she says.

Makaulule’s comrade and the chief of Duthuni Tshihe village, Nkhetheni Nevhutanda, farms avocados, litchis, lemons and bananas on 10 hectares of land on a lush hill in his village. His is not the conventional farm where crops are planted in long straight rows with sophisticated irrigation pipe systems lining the earth.

It’s an orchard he started way back in 1969. It is no different to the many orchards thriving in almost every household in Venda. They are irrigated by the rains and do not require much labour. However, the returns are big.

Nevhutanda sells his produce at markets in Gauteng and Limpopo. They have helped to school children and put them through university. They have built large homes and bought cars and continue to sustain families.

“We come from the soil. We eat from the soil and when we die we return to the soil. This is why we must look after it,” says Nevhutanda.

He believes the soil is a sacred gift and, unless it is cared for, humans and beasts will perish from hunger.

“People are dying now because they don’t follow the teachings of the elders. That is why the young die early and us the elders live longer. People are not looking after the land. They are chopping down

trees. Where is the rain going to come from if we chop down trees?” he asks.

Makaulule believes that one of the best ways to create awareness about the importance of caring for the land and sacred sites is to come up with programmes to “decolonise the minds of the people, especially young people”.

“We, the Venda people, lived in harmony with our environment. But the way the missionaries demonised and criticised our spirituality and our connection to the land made people turn away from the land and chase money. We need to decolonise the mind from depending on money. We must work the land.” — Mukurukuru Media