Straddling forms: Rampolokeng is hard to separate from his character Bavino. Photo: Delwyn Verasamy

Lesego Rampolokeng’s latest novel, Bird-Monk Seding, if one can call it a novel, is a rampaging, fast-talking, spontaneous and often opaque window into a dark, dangerous world; a world filled with injustice, suffering and copious amounts of bodily fluids. To try to describe this book in traditional terms is almost futile, given that Rampolokeng cares little for established literary forms.

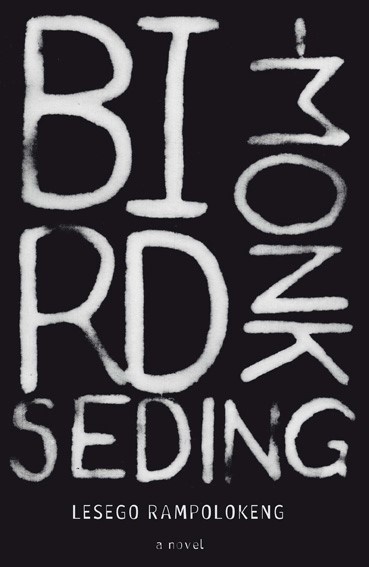

[Lesego Rampolekeng’s latest offering (UKZN Press)]

Indeed, most recently at the Time of the Writer festival, he said he never sets out to write a novel or a poem but rather he simply writes and then leaves it to everyone else to put a label on it.

One certainly gets that sense with Bird-Monk Seding, which doesn’t seem to hold to any kind of story arc. Instead it is a collection of observations, stories and asides told from the perspective of the character, Bavino Sekete.

It feels like a stream of consciousness, cut out and stitched on to even more streams of consciousness. There are italicised passages that may or may not be the thoughts of Bavino. Perhaps they are the thoughts of Rampolokeng himself.

Given his resistance to form, one finds it difficult to separate the writer from his work. Indeed, there are several passages that make a reference both to Rampolokeng’s own poetics and his ethic of writing. “… it has to be a heavy dirge, some kind of ‘death fugue’, if I were to compose or write that. Actually I am constantly doing it, always, in different ways. I just need to transcribe my cries.”

These are the words of Bavino quite early on in the novel, although they could quite easily be the voice of Rampolokeng. Bavino, in many ways, appears to be the fictionalised vehicle through which Rampolokeng is able to “transcribe his cries”.

Both Bavino and Rampolokeng are from Soweto, and both are writers. Of course, it is important that one always makes a clear distinction between the artist and their work but, with Rampolokeng, the man himself is the work.

Watching him on stage seems like performance; indeed, it seems as though he prefers to communicate through poetry (and poetic prose) than through more pedestrian means. For instance, during his Time of the Writer panel discussion, he said he often gets asked whether he has smoked crack cocaine, to which he responded “everyone has their vices”, and proceeded to read a passage from Bird-Monk describing the process and sensation of smoking it.

The reading of the passage appears to be the response. He did the same thing a little later when responding to another audience question and, instead of answering it directly, he read a passage from one of his earlier works.

This philosophy shows up in the text on page 12, where Bavino says: “I am a dabbling scribbler and I write, a lot. Of things, and ways. Forms, too. Straddling the line between poetry, prose and all that comes with. I put things on stage. Life’s theatre. And in the dust too.”

Jazz also features prominently in the book, which Rampolokeng himself is rather fond of, yet another thing he shares with Bavino. It seems as though Rampolokeng is attempting to import the methodology of jazz into his writing, filling it with improvisation, with a beat, with interwoven layers that are at times in conflict with each other, and at other times in harmony. Again, Rampolokeng’s poetics show up in the content of the text — all of the italicised asides are reflections on jazz artists or writers.

What he seems to be trying to do is hold up an example of heartfelt and soulful writing to the establishment that he believes has rejected him, to offer a response to what he believes is the sterilisation of modern South African literature. He is trying to introduce us to writing that is of the body, in all the possible ways that bodies have meaning.

A very simple sentence in the book reads: “Skin matters.” Indeed, Rampolokeng is trying in this work to explore all the ways in which skin, or the body, or the exterior, matter. Characters are often signalled as virtuous by their good looks, only to have themselves mutilated when they commit an act of vice.

Maswejana, the Pretty Playboy, is a fabled once-beautiful man, who disappointed his wife once and ended up disfigured and disturbed. Faces appear to matter a lot to Rampolokeng. Ugliness is truth, beauty is a lie, ephemeral and false. For instance, “his face is skin-pieces put together with staples. Not exactly Frankenstein-monstrous but … he is the ultimate ORGANIC intellectual.”

Rampolokeng is taking a look at how appearances affect our judgments, at the way so-called virtuous whites come to the townships to have sex with children, for example, but are still treated with reverence when they enter a shop to buy something.

Sadly, much of the time Rampolokeng’s writing style becomes tiresome and indulgent, edging towards the self-gratifying and the hypermasculine. But such is the case, too, with much jazz music. It can get lost in its own complexity.

This does not mean that this book, or Rampolokeng’s writing, is not important or exciting. His words are alive; they move and eat and shit just like we do. They feel like a too-big piece of pork we have put into our mouths but don’t want to spit out because it tastes so good, willing to embrace the risk of choking rather than surrendering the taste.

If that’s the case, then Rampolokeng has given us much to choke on.