Squandered: The court could have developed the law to include damages for trauma and grief

Three events have prompted this column: the debate about the record of the judiciary under apartheid, which arose after the death of Judge Ramon Leon and the imposition of the death penalty by Leon on Andrew Zondo; the judgment in Komape vs the Minister of Basic Education following the death of five-year-old Michael Komape, who died when he fell into a pit toilet at his school; and the majority judgment of the Constitutional Court, which found that the deliberations of the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) when deciding on judicial appointments could be made public.

As Franny Rabkin observed in her article “The death penalty and judges who had to apply it” on the imposition of the death penalty in politically charged cases, the relationship between the Bar and the handful of more enlightened judges was a Faustian pact.

Judges who sought to implement the rule of law were regarded as necessary to the fight against apartheid even if, from time to time, they were compelled to implement draconian laws, including the imposition of the death penalty.

Judgments were handed down that in effect eviscerated the pass laws, exercised some control over decisions to detain political opponents of the regime and imposed light sentences.

Leon, for example, penned an important and creative judgment in the case of (Archbishop Denis) Hurley and Another vs the Minister of Law and Order, in which he curtailed police discretion to detain without trial.

This history has never received the treatment it deserves because the record of the judiciary was not subjected to proper scrutiny by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. But the efforts of a small minority of judges helped to keep alive a belief in the importance of law as a key to a democratic future.

When South Africa received its Constitution after the 1994 elections, there was great hope that a new transformed jurisprudence would be produced by a freshly populated judiciary committed to a complete overhaul, where necessary, of the legal system that operated before the dawn of democracy.

In a number of areas of law, that challenge has been met. But in many fields, particularly of private law, even the legal imagination shown by some of the small cadre of liberal judges during apartheid has not been followed.

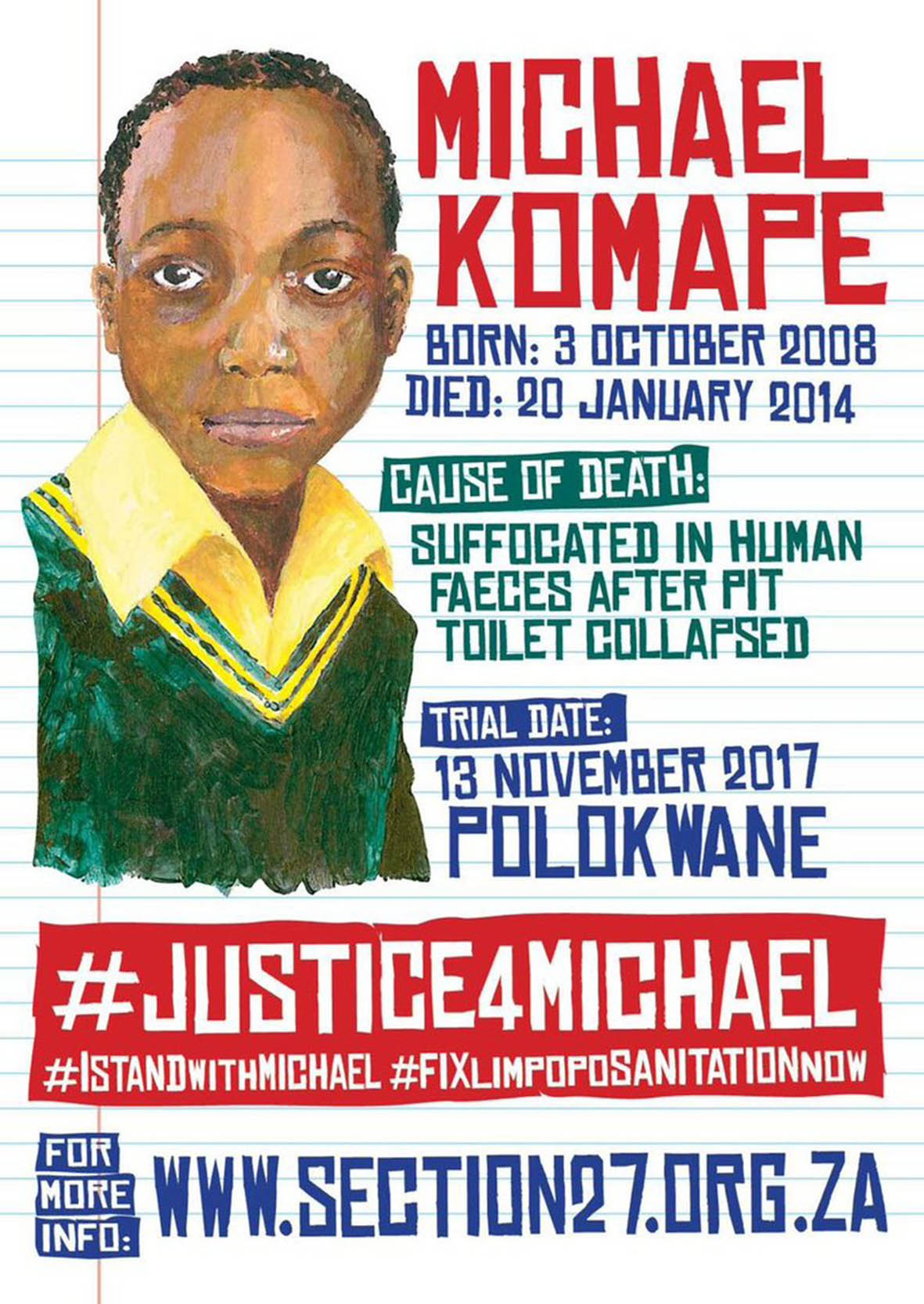

That brings this column to the Komape case. Members of his family launched two key claims against the minister and the Limpopo department of education: damages for emotional trauma and shock experienced as a result of Michael’s death, and a further claim for grief, or alternatively constitutional damages as a result of a failure to protect the child.

Judge Gerrit Muller found that, although our law recognises damages for emotional shock, there must be recognisable psychiatric harm or injury induced by a defined event to be a successful claim. The court held that to recognise a claim for grief without evidence of psychiatric harm or injury would lead to bogus claims as well as an unwarranted proliferation of claims. On the basis of the expert evidence led before the court, it could not be held that the family plaintiffs had suffered any recognisable illness.

Turning to constitutional damages, the court held that this form of claim was equivalent to punitive damages that had not been justified. An award would result in overcompensation of the family and would not serve as a meaningful deterrent to future violations of rights.

In its place the court issued a structural interdict that ordered the department to install toilets in all schools where there were pit latrines.

The structural interdict is to be welcomed in response to so egregious a form of conduct, namely that almost a quarter of a century since democracy dawned, children are compelled to attend schools that have pit latrines. But the refusal to grant constitutional damages in so shocking a case, particularly when the Constitutional Court in Fose vs the Minister of Safety and Security had kept open the door for the awarding of constitutional damages in suitable cases, is disappointing.

Furthermore, to refuse an invitation to develop the common law so as to accommodate the kind of trauma and grief suffered by the family in this kind of case is regrettable.

And that brings us to the JSC, which is responsible for the appointment of judges. A number of its decisions have prompted more than a tad of controversy, in particular the question about its decision-making process concerning the commitment of a candidate to the transformation of the legal system and the ability and record of the candidate to meet the challenges to the legal system posed by the advent of the Constitution.

The judgment of the majority of the Constitutional Court, holding that a blanket ban on the disclosure of the deliberations of the JSC could not be legally justified, may provide better insight into how the JSC treats questions about this transformation.

Although disclosure may only take place when a JSC decision is subjected to judicial review, the threat of disclosure may promote the kind of comprehensive debate before an appointment decision is taken, which in turn could mean that the vital importance of jurisprudential philosophy will be central to the process. The case of Michael Komape should be a reminder.