(John McCann)

As South Africans reel from two bank collapses in the past four years, authorities have been steadily overhauling the entire legal architecture of the country’s financial services industry, aiming to prevent similar implosions in future.

Only time will tell whether the new “twin peaks” regulatory regime, as it is known, will prevent failures such as those at African Bank and, more recently, VBS Mutual Bank.

Implementing the twin peaks model will cost more than current regulation — about R1.4‑billion by 2020 or what equates to a 42% increase in the budgets of the existing regulators . It will also require an unprecedented level of co-ordination and co-operation by regulators, say industry players.

Increased costs notwithstanding, industry experts argue that the benefits of better regulation outweigh the costs of implementing it.

The Financial Sector Regulation Act was promulgated in August last year and brought into being the two regulatory “peaks” — the prudential authority, housed in the South African Reserve Bank, and the Financial Sector Conduct Authority (FSCA), which replaces the Financial Services Board.

Both the prudential authority and the FSCA were launched last month, although work towards establishing them has been years in the making.

The prudential authority will oversee the soundness of financial institutions that provide financial products and services, as well as the soundness of market infrastructure such as clearing houses and securities exchanges. As a result, the twin peaks model extends the reach of what was once the banking supervision department in the Reserve Bank — to scrutinise not only the soundness of banks but also of insurers and entities such as the JSE.

The FSCA will regulate all financial institutions, including banks — which the FSB did not oversee — from a market conduct perspective to ensure they treat customers fairly.

Twin peaks is the biggest change in the South African financial sector’s regulatory landscape since demo-cracy, Finance Minister Nhlanhla Nene noted recently. It will require overhauling a range of laws and introducing new ones, including a Conduct of Financial Institutions Bill, a draft of which is expected later this year.

Cost concerns

There will be increased regulatory costs in the form of levies and fees to fund the expanded mandate of both regulators, as well as other bodies that will be created under twin peaks — such as the Financial Services Tribunal and the Ombud’s Council.

The overall costs are still to be determined, as a draft levies Bill governing the fees structure is still making its way through Parliament.

One estimate for a large commercial bank suggests costs will rise from about R300 000 to more than R40‑million on the prudential side alone. These estimates do not include what a bank will have to pay for additional staff and systems to meet compliance requirements, expected to be about three to four times the cost of the regulatory fees themselves.

In a recently updated study on implementing twin peaks, the national treasury outlined the cost implications.

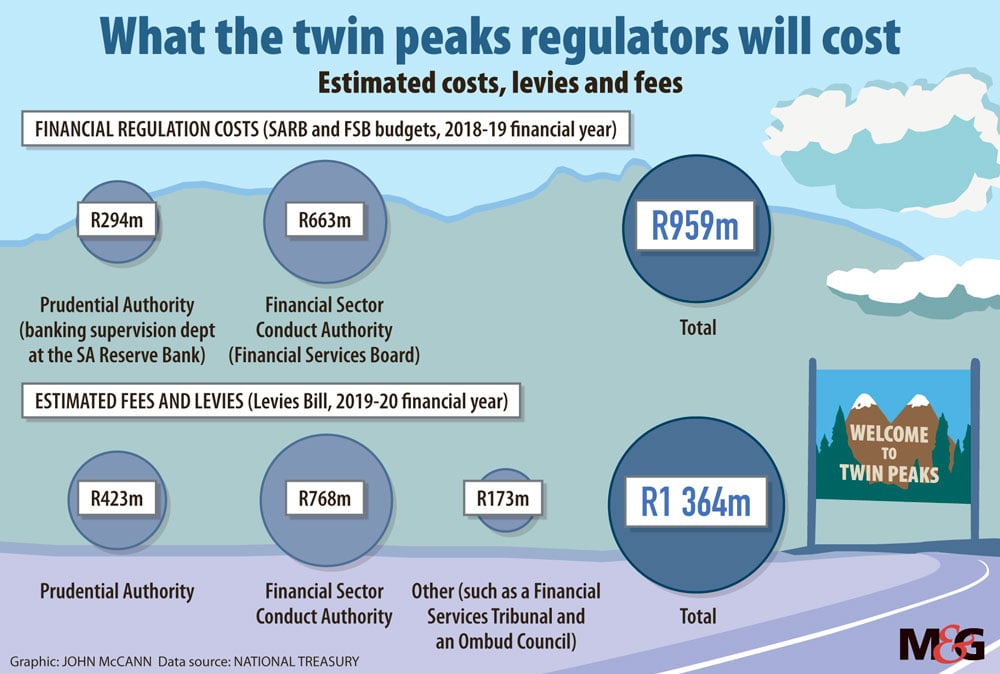

For now, the two new regulators will be funded from existing sources for the 2018-2019 financial year, according to the treasury. In the case of the FSCA, these sources are levies and fees raised under the Financial Services Board Act, amounting to just under R663‑million. The prudential authority gets its R294‑million funding from the Reserve Bank. The envisaged levies are expected to kick in during the 2019-2020 financial year.

Once fully operational, the new levies and fees for the prudential authority are estimated to reach about R423‑million by 2019-2020 and R768‑million for the FSCA; fees for other bodies such as the Ombud Council are expected to be in the region of R173‑million. This will amount to almost R1.4‑billion or 42% more than in the current financial year.

But the treasury says in its assessment that when comparing banking supervision costs for the prudential authority, the levies on banks — when compared to the previous year’s budget — wil be 8% lower.

“This effectively means that the cost of regulation for banks will be reduced and this could be attributed to benefits from economies of scale,” the treasury maintained.

The industry has raised concerns about costs, particularly in interactions with the prudential authority, said Cas Coovadia, managing director of the Banking Association South Africa. The authorities will have to be transparent about how levies are used and must properly account for them, he said.

The banks would largely absorb the regulatory costs but some may be passed on to consumers, he said.

Rich data = better decisions

The treasury said regulation in the financial sector has been typically funded on a “user pay” principle, requiring the institutions “that benefit from a robustly regulated financial sector” to be levied for this purpose.

Relying on the fiscus for funding can hamper the ability to achieve effective regulatory and supervisory outcomes, it said. Extensive reporting and accountability measures are imposed on the new regulators, through the Public Finance Management Act and the Financial Sector Regulation Act.

Anthony Smith, a partner in the risk advisory practice at Deloitte, noted that the emphasis on conduct in industry-related matters has been long coming — but that a lot of spending directed to these issues could be considered “good practice in the first place”.

“One could argue that a financial services organisation should have been analysing this data and information to adequately run their business and truly understand their customers,” he said.

The richness of data provided for reporting can be used to make better business decisions, he added.

There will be an increase in an institution’s headcount, systems, monitoring and enforcement, resulting in higher costs, Smith said, which “will be passed on to the consumer either via taxes or levies imposed on the sector, which will translate into higher bank charges”.

But it was important, from an “SA Inc point of view”, that the country was, and was seen to be, taking steps to increase regulatory oversight and protect depositors’ money, Smith said. “The benefit that comes through enhanced reputation and consequently increased investment has been shown to far outweigh the costs of doing it.”

Nevertheless, compliance-related costs will continue to increase, he warned.

“There have been significant cost increases over the past 10 years, resulting largely from the response to conduct-related matters such as mis-selling, reckless lending, price fixing and fictitious accounts that continue to plague the industry,” said Smith.

Although there will be additional costs, there are also efficiencies being built into the system, the FSCA’s Caroline da Silva said at a recent workshop on the implementation of twin peaks.

“A bank or insurer might have 16 [financial services provider] licences; all of those have a cost. In future, they will have one licence, one supervisory team, so there’s efficiencies being built in,” she said.

Co-ordination imperative

The policy decision to exclude the National Credit Regulator (NCR) from the twin peaks architecture has baffled industry players and has been described as a missed opportunity. The regulator, which falls under the ambit of the department of trade and industry, is responsible for regulating the credit industry under the National Credit Act.

It is one of the reasons the Democratic Alliance refused to vote in favour of the Act in Parliament.

The DA’s Alf Lees said the effect of the decision not to include the NCR under the FSCA will render the conduct authority toothless in the credit industry. It would also compromise an important objective of the Bill, which is to improve the co-ordination of financial sector regulators in South Africa.

But Da Silva said this did not mean the FSCA would have no authority over the credit sector. According to the Financial Sector Regulation Act, the NCR will be responsible for the contracting of credit and the FSCA will be responsible for the conduct around the provision of that credit, she said.

What this will mean in practical terms is being discussed as part of a memorandum of understanding being signed between the NCR and the FSCA. It will determine where the NCR’s jurisdiction ends and the FSCA’s begins, Da Silva said.

The co-ordination between regulators, especially the prudential authority and the FSCA, will be a key test for the new regime, said Rosemary Lightbody, a senior policy adviser at the Association for Savings and Investment South Africa.

“It will be very frustrating for, and will hamper, business if the communication between the two authorities is not smooth,” she said. But if twin peaks delivers on what has been promised, including more timely and appropriate regulatory intervention, the additional costs of regulation under twin peaks could very well be worth it, she said.

Some lingering questions

But would the implementation of twin peaks have been able to prevent a collapse of African Bank or the recent crisis at VBS?

According to Unathi Kamlana, the head of policy, statistics and industry support at the prudential authority, “no framework is foolproof. It’s about how … one is empowered, as a regulator, to deal with failure when it occurs.”

Twin peaks confers a range of new powers on the regulators aimed at establishing a more proactive, risk-based approach to regulation. In the case of the prudential authority, the twin peaks regime creates an supervisory framework for systemically important financial institutions, such as major conglomerates.

Kamlana said that, until now, the Reserve Bank’s supervisory role has extended to the holding company of a bank and the entities that fall under the holding company. “But there might be other interests in a broader financial conglomerate [with] risks emanating from entities that are not consolidated within the scope that we have oversight of, which have implications for the prudential soundness of the group,” he explained.

To combat such risks, the twin peaks regime provides new powers over such institutions, including the ability to order the restructuring of a conglomerate. According to the treasury, the FSR Act also provides regulators with more information- gathering powers than previously. These include “intrusive” onsite visits, typically with a warrant to obtain information, and have already been used in the case of VBS, it said.