Grand dame: Esther Mahlangu

Shallow calabashes filled with clay and cow dung sit on the stoep of a hut on a farm just outside Middelburg in the late 1940s.

A preteen Esther Mahlangu alternates between dipping chicken feathers and thick plant roots into the calabashes. With narrowed eyes, she applies the thick pastes on the hut’s walls with gentle, eager strokes. Mahlangu is beginning to learn the Ndebeles’ painting techniques and is restricted to the back wall of her home.

This ritual of a cross-legged Mahlangu painting and repainting the same patterns, on a part of the hut hidden from visitors’ views, continued. With no maths set, rulers or stencil, she practised the symmetrical circles, triangles and straight lines of the geometric patterns that characterise Ndebele artwork until the matriarchs, who were teaching her, approved of her work and allowed her to paint on the front walls of the house.

The inherited pride of the cultural practice and process planted a seed that groomed the young Ndebele girl to become the Dr Esther Mahlangu we know today.

Her latest work is a mural at the Nirox Sculpture Park in the Cradle of Humankind, part of the 2018 winter sculpture exhibition, Not a Single Story, which opened last weekend and will be on show until July 29.

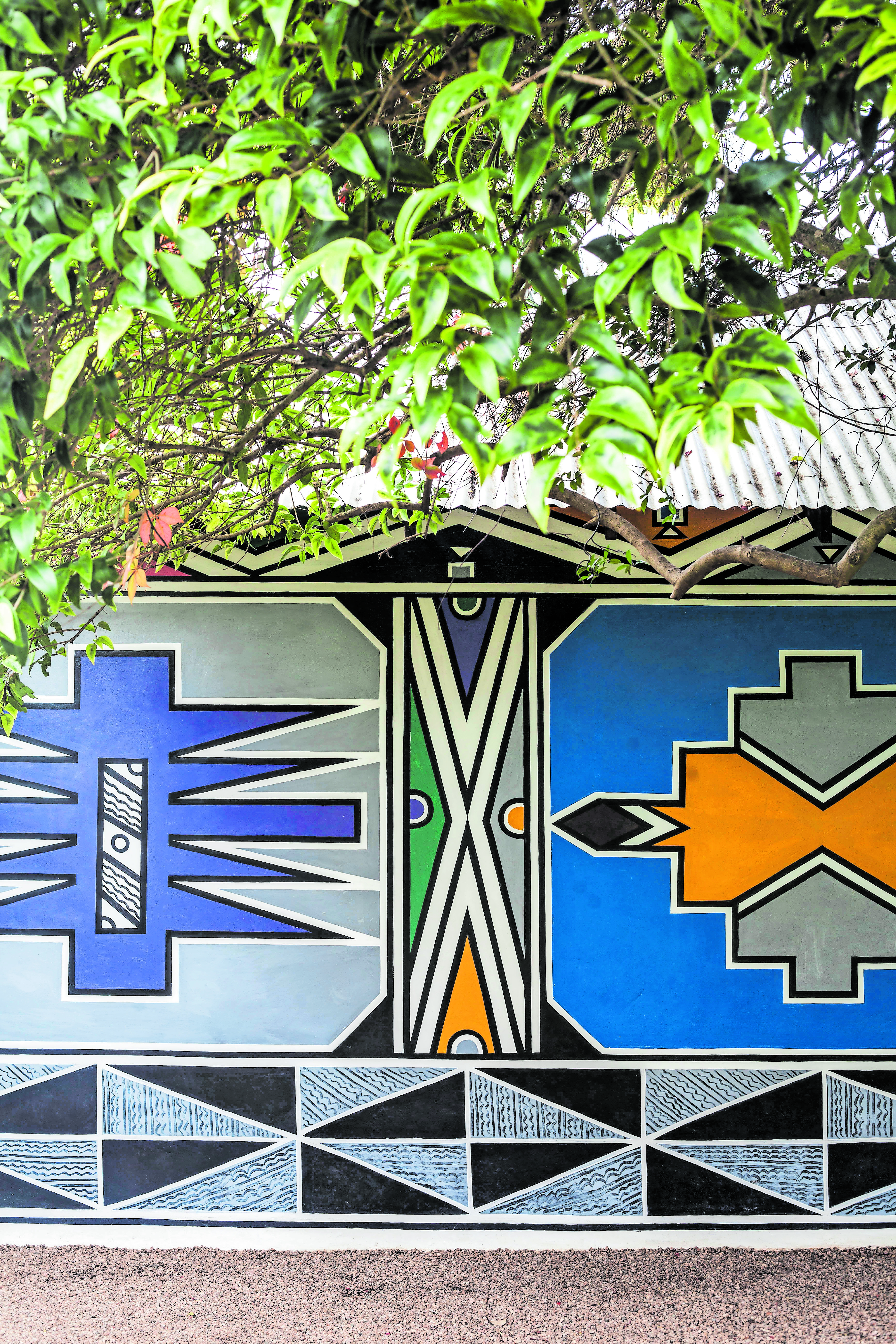

[Ancient script: Ndebele artwork is derived from a historical lexicon using geometric and colour symbolism to convey messages and has now become a recognisable mark of Matebele identity. (Oupa Nkosi)]

Its title was inspired by author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s TED talk, in which she warned against limiting people’s experiences to a single perspective. To bring this message across, the exhibition predominantly features the works of women artists from South Africa and around the world, including Nandipha Mntambo, Jane Alexander, Nelisiwe Xaba, Yoko Ono, Mary Sibande, Lena Cronqvist, Beth Armstrong, Mwangi Hutter, Ayana V Jackson, Frances Goodman, Caroline Mårtensson, Claudette Schreuders and Mahlangu. An arts education programme will run alongside the exhibition.

“Learning to paint was the equivalent of going to school in those days. You see, you got to go to school and even university. That didn’t exist for us. So we painted. It was how we showcased our intelligence,” says the stalwart by phone. She is in Portugal working on a new mural commission.

“When you painted on the wall of your homestead, you were showing your community what you know and who you are. If you painted badly, it was a reflection of the home you came from and your dedication to the craft. If you painted well, you were the equivalent of a learned girl in today’s context. It earned you the respect of your peers,” explains Mahlangu.

By 1986, when French curators from the Centre Pompidou were introduced to Mahlangu, the artist had been honing her craft every day for just over 40 years — first in her parental home and then in her marital household. When there was an addition to the family, a loss or any other significant event, Mahlangu painted because, before it became her living, it was a language.

She laughs at the memory of how the French “discovered” her.

“Oh no! Local curators saw the artwork at my homestead and recognised how beautiful it was. They insisted that I start working at their museum [Botshabelo Museum]. Then a white man from France by the name of Andrew, I don’t recall his surname, approached me to go overseas. But that’s not when I became an artist.”

The memory Mahlangu recalls refers to her first international group exhibition, Les Magiciens de la Terre, The Magicians of the Earth. At this exhibition in Paris, during a State of Emergency in South Africa and at a time when the country was isolated from the world, the 50-year-old Mahlangu painted a replica of her house ngesiNdebele while the public watched.

READ MORE: The South Africans in Paris make most of ‘Being There’

What seemed like a simple act on her part became the Western world’s introduction to the Ndebele heritage and its reliance on artistic expression.

Before she became the recognised figure she is today, the Ndebele artwork she grew up doing was limited to the natural colours of brown, black, white and ochre. By pioneering the use of primary colours and being the first to place Ndebele artwork on canvas, Mahlangu furthered the art form’s reach.

Although the response to her work pleased her, Mahlangu returned home wary of what this might mean for her heritage. But, by then, formal education structures had been put in place, so young girls were no longer being taught how to paint by their matriarchs.

“My objective became passing on my artwork to the next generation so that the authenticity of Ndebele art does not fade away. So I gathered the young people who lived nearby and began passing the skill on to even children who were not my own. I taught my students by giving them a sample of my work and ordering them to copy what I had painted on pieces of ceiling board.

“After attempting to replicate my work, I critiqued their attempts, sent them back to redo it and repeated this process until they perfected my pieces. By doing this, they began to grasp whatever I presented to them. Now they have it forever.”

By so doing Mahlangu cemented her local relevance as a holder of indigenous knowledge.

After pioneering the move from walls to canvas as a way to teach the skill, she began to paint on canvas to sell the portable pieces to tourists, commercialising indigenous expression on her own terms.

Once the door to the commercial world opened, Mahlangu’s commissioned work was no longer isolated to the white square. Instead, collaborations have included the likes of BMW, Fiat and Belvedere Vodka.

What was once solely a visual lexicon between community members became a globally celebrated artistic mark of the Matebele. Her undying vision of all objects as potential canvases, and her dedication to teaching younger generations the art form, reinforce her objective of preserving the Ndebele knowledge systems by archiving this visual lexicon in a manner that sits comfortably in the domestic space, the commercial world and the artistic sphere.

“The collaborations are quite fun for me because I feel so special. What I learned from them was furthering my spirit of ubuntu. There has not been exploitation on my side. I only experience eagerness from people who appreciate my work. People really want to learn. They respect me and my work, they know that I am the holder and the teacher of this beauty, so they would never try to exploit me,” says Mahlangu, who is cautious enough to move in these global spaces with an intellectual property lawyer.

For these continued efforts, Mahlangu was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Johannesburg’s faculty of art, design and architecture.

The teaching of art in part of her home in Mathombothiini near KwaMhlanga, Mpumalanga, continues with funding from her own pocket. Recently, the municipality and other sponsors have contributed, enabling it to become a formalised indigenous art school.

“I have always had the calling to teach the science and significance of Ndebele painting, and why we paint. In my school, not only will I be teaching them the Ndebele art form but also the language and cultural aspects, along with the origins of the Ndebele people. You cannot separate the art from the language, culture and the people, because that is where it came from.”

Mahlangu’s focus is on isintu samaNdebele (Ndebele heritage and culture) and she hopes her efforts will encourage the carriers of artistic indigenous knowledge of South Africa’s other indigenous groups to do the same.

“That is not my focus; I am not the gatekeeper of all South African art. I only want to work with, teach and preserve Ndebele artwork. That is what I know. I appreciate other art forms coming out of the country because I don’t know their origin.”

After spending more than 40 years in the art world, Mahlangu is pleased with the canon of work she has managed to create, preserve and celebrate Matebele. Although she is pleased with the accolades, she is aware that the work of preservation does not end.

“I’m content with how far I have come but I will continue to paint until I am no more. I just have one more dream to fulfil. My dream is to receive more accolades from various government departments. This will help with funding for my school. But I also wish my art stays alive when I am no more.

“And when you speak of me, remember me as a South African ambassador who never grew tired of teaching and representing isintu.

This interview was conducted in isiNdebele and translated into English by Zaza Hlalethwa and Nsizwa Mahlangu.