Philip Tabane with his son

The honour of having chaperoned guitarist and sound architect Dr Philip Nchipi Tabane to his last gig went not to his biological son, with whom he has often played, but to an offspring nonetheless.

Percussionist and songwriter Azah Mphago, a childhood friend of Tabane’s musician son Thabang, grew up being groomed for his role in the malombo lineage.

“It was more an honorary appearance to honour the man,” says Mphago of the May 27 2017 performance at the Roots of Humankind Festival held at the Nirox Sculpture Park in the Cradle of Humankind in Gauteng.

“It was like he was taken out of retirement. He was fragile and what have you. The speed [of his playing] wasn’t as sharp but the beauty of it was that he was a man who knew how to be a part of everything as it was. My role on that day was to create the background for him and allow him to create the music as he saw it then.”

On that day, Mphago and Tabane played just one song, Lefatshe, a 10-minute lament resisting and mourning the loss of pastoral wealth. It appears on the late-1980s album Unh!

“Lefatshe connects us to the issues of land,” says Mphago, in a manner that suggests that Tabane’s last public utterance was selected for its symbolism.

For Mphago, Tabane is perhaps more important as a philosopher than he is as a musician — not that the two could be separated in Tabane’s case. As he tells it, Dr Malombo always prefaced their musical interactions with what West Indians would term “building a vibe”.

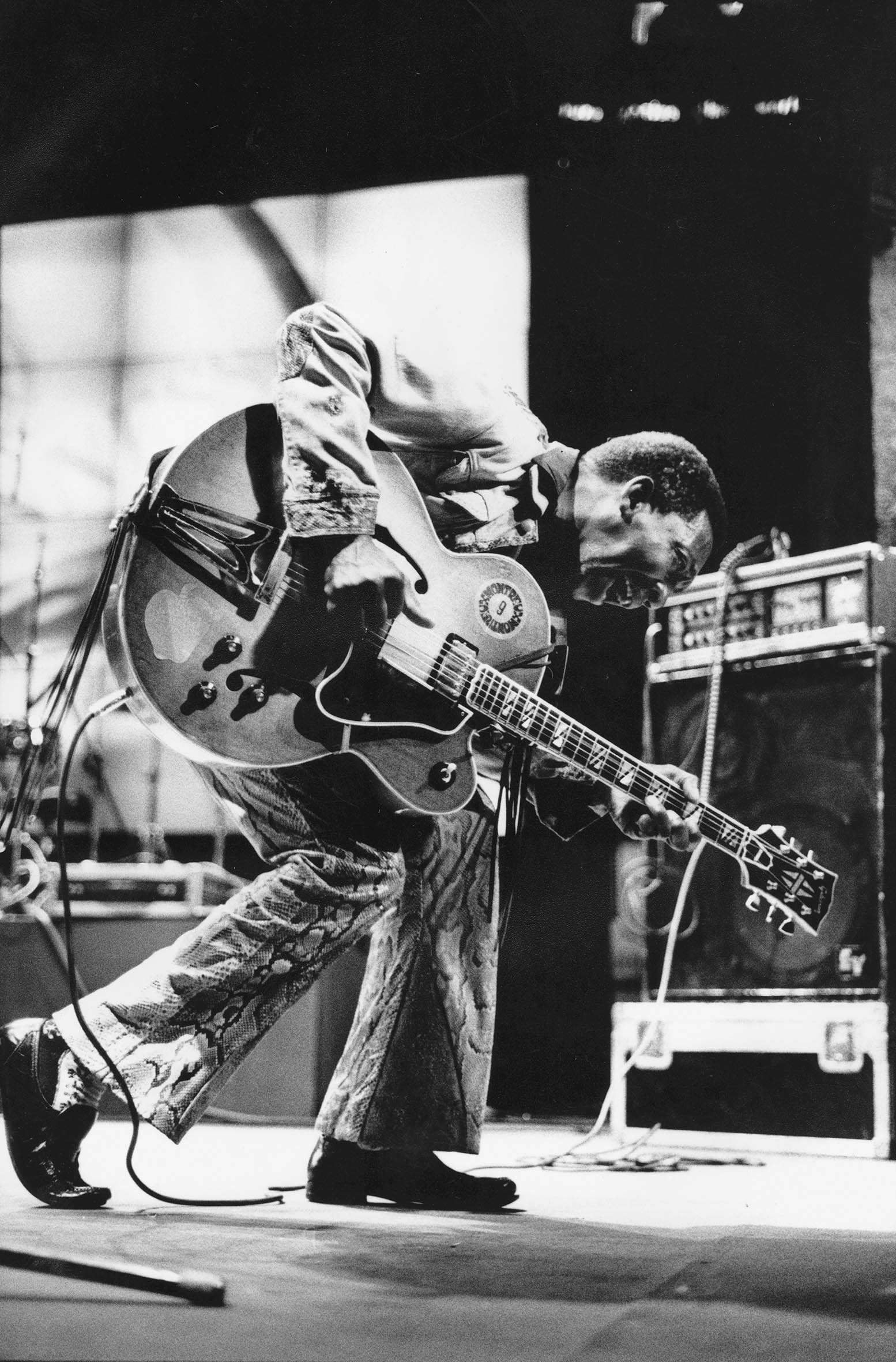

[Impeccable timing: Philip Tabane performing live on stage in 1993 (Photos: Motlhalefi Mahlabe/South Photos/Africa Media Online)]

“His teaching style, be it music or life philosophies, has always been simplistic,” says Mphago. “He always encouraged us to be observant of everything around us, because everything around us informs who we are. To see everyday situations as divinity. It’s in the simple things like how we interact with each other. There are interactions that are invisible but are quite important.”

Mphago describes their pre-rehearsal ritual as “one of conversation: about family, the weather, but filled with laughter. These are the moments where, as a disciple, you’d grab a lot of warmth that would later be infused into the music.”

Various people of differing proximity to Dr Malombo regard his comedic and oratorical timing as not dissimilar to his approach to music; a free, performance-driven approach where no song was relayed in the same way twice.

In conversation, almost as it were in the music, there were long bouts of silence followed by incisive and unforgettable aphorisms.

Born in Riverside, southeast of Pretoria, in 1934, Tabane grew up in a family of musical siblings, learning the pennywhistle at the age of seven and the guitar from an older brother at the age of 10. The family relocated to Mamelodi in the 1950s because of apartheid policies.

At Johannesburg institutions such as Dorkay House and the Federated Union of Black Artists (Fuba) centre, Tabane furthered his musical education and became steeped in the political and creative milieu of the times.

But it was his mother, a healer, whom he regarded as his first musical and spiritual mentor.

“It was from her that Philip aspired to retain the spiritual link with [his] ancestry which pervaded his musical purpose and expertise,” writes Sello Galane in his PhD thesis, which analyses the music and philosophy of Dr Malombo.

Malombo, as a musical approach, was a call of the ancient mixing with Tabane’s contemporary surroundings. By design, it mirrored his personality and outlook, musical timing reflecting the raconteur.

“If he didn’t like something, he’d tell you, no matter who you were,” says one-time manager Peter Davidson. “He had that quiet strength where he never had to speak much, but when he did, he’d regale you with many stories. But after a certain point, you knew you couldn’t get very far with him. He didn’t understand diplomacy.”

Davidson, who regards Tabane as a brother, first met the musician through his music and later helped him to take his sound to the United States.

“Somebody brought a record from South Africa, the Castle Lager Jazz Festival 1964,” says Davidson, who lived in Swaziland at the time. “On the one side it had Malombo Jazzmen, and on the other side the Chris McGregor jazz band. This music really resonated with me because it was unique and it was unmistakably African. While I was in Swaziland, I met Philip. He performed at Julio’s cinema in Manzini, probably in 1971, somewhere there.”

Davidson, who had been a road manager for the then-exiled Hugh Masekela when his 1968 hit Grazing in the Grass was tearing up the American charts, used his contacts to get Dr Malombo to the US.

By the 1970s, Tabane had established malombo as a sound, the alchemy of which was in tune with the rising swirl of the Black Consciousness Movement.

The album Davidson had in his possession featured the initial malombo lineup (in which the group was named as such), comprising Julian Bahula on hand drums, Tabane on guitar and Abbey Cindi on flute. But that lineup did not last long, and Tabane pared down his unit to just himself and his nephew, percussionist Mabi Thobejane, by the time he was ready for the US.

His first clutch of gigs was at Rafiki’s in Manhattan, a residency that led to a tour of the country and frequent, extended stays in the US.

The 1970s were also a period of expansion for Dr Malombo. He tinkered with how to expand his sound, giving the US market a try without reneging on malombo’s raison d’être. There were shows, for example which featured a young Bheki Mseleku on keyboards.

Davidson says his and Dr Malombo’s professional relationship was cut short by a run-in with the law at Heathrow Airport, when the malombo entourage was in town to score the anti-apartheid film Last Grave at Dimbaza, which was released in 1974.

Davidson took the rap for the stash of cannabis found in the entourage’s baggage, allowing the doctor to complete that intuitive score that gives Last Grave its emotive impetus. As for Dr Malombo himself, he abandoned the American project with little explanation in the late 1970s, returning to Mamelodi.

In those years, malombo as helmed by Tabane was popular culture untainted by pop sensibilities. The 1980s, however, brought with it a different popular aesthetic but by no means diminished the urgency of Tabane’s message, as evinced by its continuing presence in the South African music scene.

It was Unh! (recorded in New York in the late 1980s) that turned guitarist and producer Selaelo Selota into something of a malombo devotee. But malombo’s magic, its minimalism, its agenda that was inseparable from the will of the people, had been creeping up on him since his days as a Fuba student in the 1980s.

“The director of the centre usually took us to concerts and encouraged the up-and-coming school bands to perform,” says Selota. “The first place I experienced that, they had organised a show at the civic centre there in Vosloorus. Ntate Tabane was performing there with his group. But at that time, I must add that most of us were very much impressioned by the Western sounds. They were in fashion and so on, and we hadn’t encountered anybody who confronted tradition and culture with music, using modern instruments like the guitar and combining them with drums. That led to me forming a duo. Ntate Tabane had a group, with just Mabi Thobejane. I also formed a group, with just Philip Shaba, and we called the band Chimurenga. I started performing like that at Fuba, and the centre started taking notice. But that was just the beginning, because that was around 1987.”

Through all that time, Selota and Tabane never met.

“In terms of me understanding his music, I come from a background where there is malopo and those kinds of ceremonies around me. So therefore I understood what was happening in his music. If I play in an African set-up, Hotstix Mabuse would come and say I have very percussive style of guitar playing. I hear drums, drums that are not being played sometimes, guitar rhythms interlocking with imaginary drums.”

Mamelodi native, guitarist Vusi Mahlasela regards Tabane as the master of improvisation; playful, gimmicky, serious and surprising all at the same time.

Perhaps a testament to Tabane’s sense of humour and impeccable timing is to consider that his funeral, his return to the essence, will come exactly a year after he sang his last song at the Humankind festival. As he once told Mahlasela, so is his message to all of us: “Always return to yourself.”

The funeral service will be held on Sunday May 27 at Vista Mamelodi campus at 8am