While her performance at Bushfire Festival was colourful and energetic

In its twelfth edition, Bushfire festival has found its lifestyle stride with markets, food and camping facilities abound, but the music programming is paying the cost. At most times of the year, a drive from Johannesburg to The Kingdom of eSwatini (formerly Swaziland) and back makes for a relatively convenient, inexpensive, leisurely excursion to our monarchic neighbour. Complete with tattooing stamps into passports at the border, mispronouncing siSwati words and making a general and typically South African nuisance of oneself in another country, the feeling of visiting bakaNgwanehas its unique sense of voyage.

In the last weekend of May though, when Bushfire festival in the Malkerns Valley stages the music portion of its week-long programming, South Africans descend on their neighbours in droves, congest the borders into eSwatini on Friday and out on the Sunday. Interestingly, this year the border queues were disproportionately clogged on the South African sides by more than an hour’s wait at worst. Swati officials, on the other hand, made sure not to let a single Rand or Emalangeni of the 33 million the festival pumps into their economy slip. During this period, it becomes next to impossible to find accommodation for a single or multiple nights’ stay anywhere close to Malkerns.

With so many South Africans bent on a weekend of debauchery in Africa’s green gold capital, the memo about how visitors behave clearly didn’t reach every inbox. More than a handful of times over the weekend, punters proclaimed eSwatini as South Africa’s 11th province, after Lesotho of course. It was also bad enough that during rapper Kwesta’s set, his backing band’s guitarist shredded and electric rendition of the South African national anthem. But the enthusiastic cheers thereafter were even more humiliatingly offensive.

Of the 92 acts on the programme, 38.5 were South African (with the .5 being collaborations between South African and musicians from elsewhere). Seems reasonable at first, considering that South Africa’s population is roughly 42 times that of Swaziland. Numbers can lie, though. Of the 24 acts on the Bushfire main stage, half were South African. Most of the main stage acts were accompanied by live bands. This gives a clearer idea of how the cost of staging major acts and the prominence acts are given leans overwhelmingly in favour of South Africans.

Swati musician Sandziso “Sands” Matsebula of Tigi fame attributes the skewed programming to the size of the South African music industry and audience compared to those in his native eSwatini. Conversely, however, keeping his roots front and centre has been instrumental in his recent career success. “It’s (Kingdom of eSwatini) been one of those countries that has been neglected, it hasn’t really been explored much in music so it did help me sell to just keep being Swazi. Also for my ancestors,” he says half-jokingly “to also know that I am still theirs, you must be in touch.” Things have not always been this way. Christian Syren, director of Making Music Productions and member of Salif Keita’s management team for more than two decades, remembers how the South African industry developed to supersede its neighbours and other countries in the South African Development Community (SADC) region. According to Syren, the population size and overall economic development of South Africa played major roles in putting it where it is musically in the region. He says “After 1999 South Africa was growing a lot faster and our industry became a lot more professional quite quickly after 1994 whereas you can’t say the same thing for Zimbabwe and Mozambique, for example.”

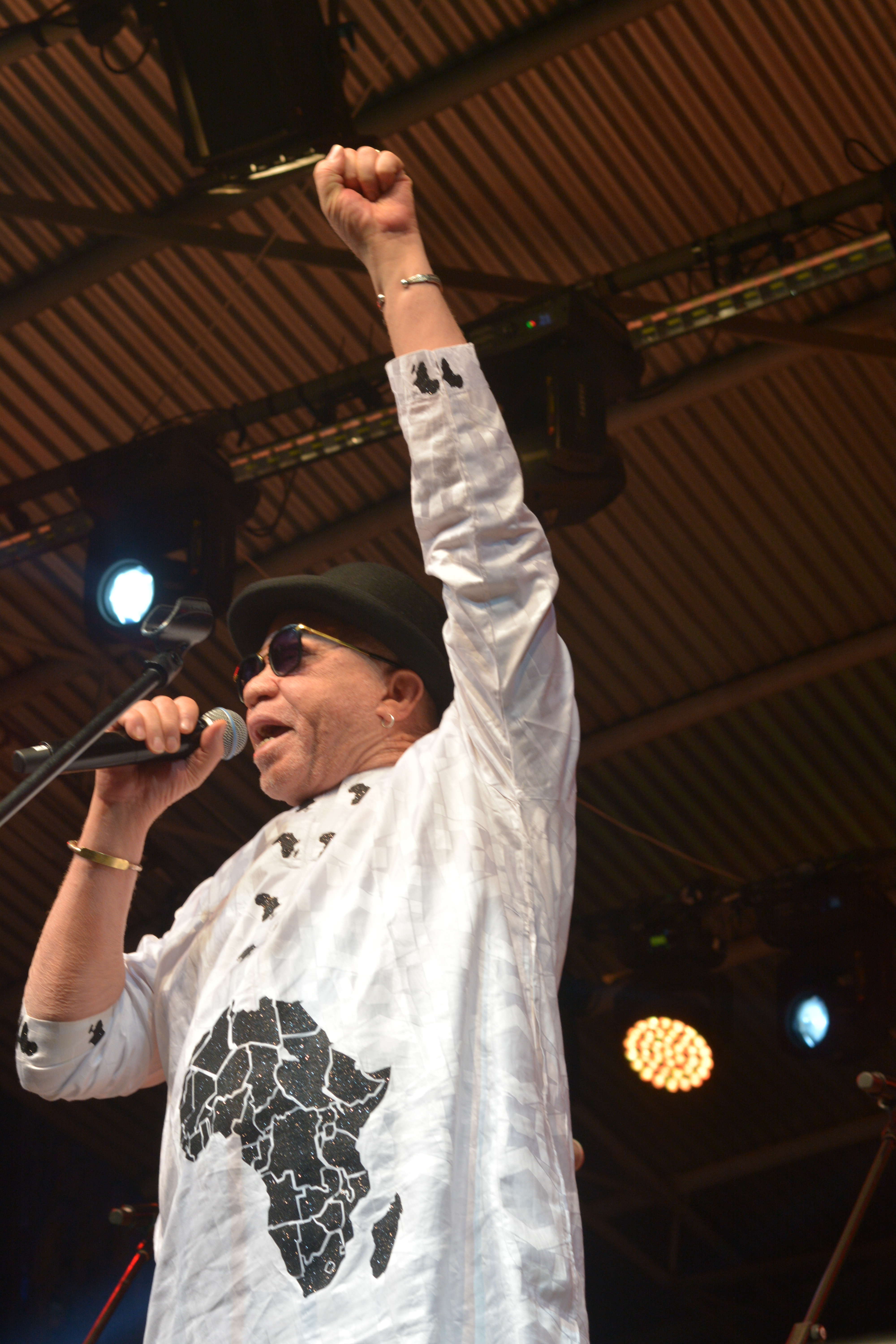

[Salif Keita can signpost the direction in which some of his juniors should be heading in (Thebe-Mohlomi)]

What is potentially dangerous for the festival circuit is the prominence of South African acts because of their potential of establishing trends and mainstream music modi operandi. From Bushfire festival alone one notices a trend in contemporary South African music of placing performativity and aesthetics ahead of musicality. Sho Madjozi, known for her Tsonga language rap hit, Dumi Hi Phone, is a case in point. While her performance was colourful and energetic, her voice struggled through the scheduled set. She often audibly battled to recover after songs in order to hype up the audience and catch a breath. Similarly, Dear Ribane & Okzharp’s performance was remarkable for its costume design and Manthe Ribane’s contortionist choreography. But musically, the performance left tons to be desired.

It would be unfair to compare Keita and his musical career which will next year span 50 years to the formative careers of South African contemporary artists. But perhaps the doyen of Malian and indeed African music can signpost what direction in which some of his juniors should be heading. Keita, says Syren, first performed in South Africa in 1994. Syren travelled with the t-shirt that was made for that concert. It would be a pity if that t-shirt would outlast the talent and potential abound in South African contemporary acts.

More devastating would be the nascent touring network succumbing to the tides of popularity over hosting quality, well curated shows. Bushfire festival is not alone in paying increasing attention to the fringe activities meant to support the festival experience. Internationally, festivals have realised that their audiences are not made up solely of music lovers who travel to their events for the sheer pleasure of seeing their favourite acts live.

The craft and food markets played a prominent role at this year’s festival. Mainly Swati vendors had a variety of material and culinary offerings which could all be purchased with a newly fully integrated cashless system, which has become an international standard. The art of hosting a festival with many moving parts and serving different pockets of audiences is to strike a melodic balance between the sundry offerings and the curation of music.

The shining moment of Bushfire’s main stage contrasts starkly with what was arguably its dullest moment. Samthing Soweto, who’s beginnings were with the a capella group The Soil, took to the main stage on Saturday afternoon and drew a crowd which seemed to have followed his musical trajectory to the present. They made this known with their voices which rose to meet him in chorus, word for word. But what he failed to deliver was a coherent and considered set. Instead, at some point during his show he rendered himself a jukebox, asking the audience what they would like for him to perform. “The funny thing is that’s not even my song,” he exclaimed after an audience member did what one does with jukeboxes- request whichever song came to mind in the moment. Although Keita was ill and defied his doctor’s order in travelling to South Africa and Swaziland to play his shows, he was able to enrapture the audience without stage antics. Instead, his voice became the central attraction and he delivered a moving musical rendition of his own compositions alongside Ladysmith Black Mambazo and Yemi Alade. Of course this comes with years of gigging and touring.

While Igoda, the festival network which shares artists and expertise across five festivals in the region has breathed musical life into the festival programmes involved. The financial model on which Igoda’s foundation is based is a long known truth. Touring a single major artist, whether they be African or from elsewhere is more lucrative when they play numerous shows instead of one. What Igoda is making audiences realise anew is that the dominance of South African acts when it comes to programming might be a boon for the box office but a curse for the discerning, music loving festivalgoer. And perhaps this type of punter is a dying breed, to be replaced by a mutation which attends festivals for “lifestyle” and “a vibe”.