Contrary to orthodox economics

Recep Tayyip Erdogan is a fan of cheap money.

Contrary to orthodox economics, Turkey’s president believes that lowering interest rates in turn lowers inflation. In line with his unconventional conviction, he has put pressure on the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey to keep rates artificially low, creating imbalances in the economy.

But last week he lost the battle to a bigger force than himself — the global markets.

A strong dollar and an interest rate hiking cycle in the United States have investors demanding much more from emerging markets and those with weak economic fundamentals are primary targets. Turkey is the bull’s-eye.

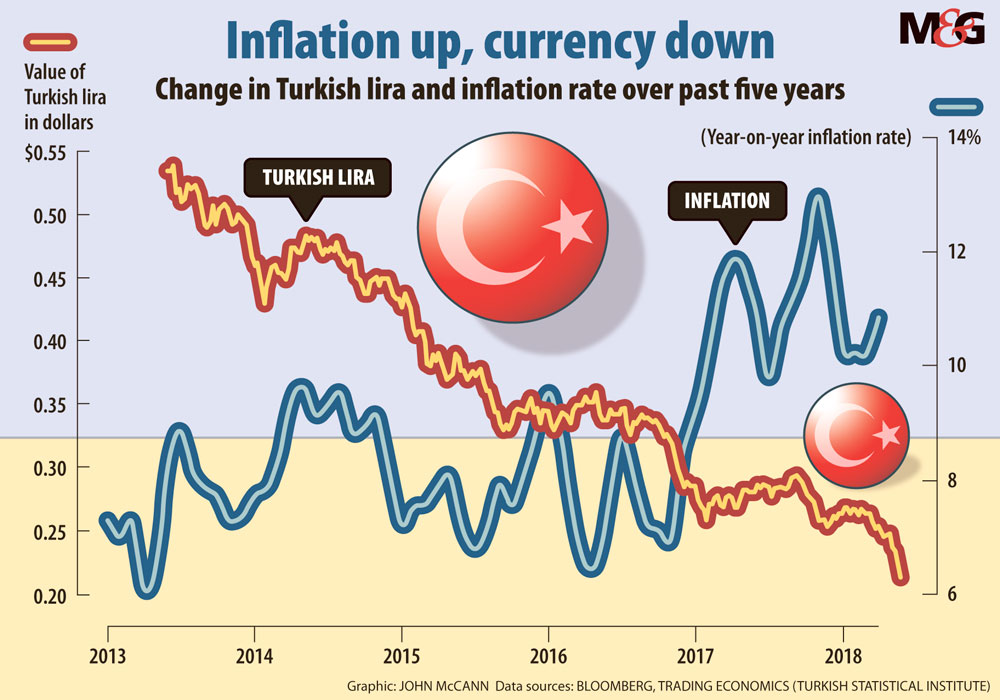

Its lira had fallen by 22% since the beginning of the year, and when at its weakest level of 4.90 to the US dollar last week, Turkey’s Central Bank was forced to hike the key interest rate from 13.5% to 16.5%.

“Turkey has been by far one of the hardest-hit countries in the recent EM [emerging market] financial market sell-off. The lira is the worst-performing EM currency this year after the Argentine peso,” said Jason Tuvey, an analyst at Capital Economics, a independent London-based research consultancy.

“Pressure on the lira has reflected a number of factors, including the large current account deficit, high and rising inflation, and concerns that political pressure for lower interest rates is undermining the independence of the Central Bank.”

Real interest rates (after inflation) are much lower than what Turkey requires given its history of high inflation, last measured at 10.85%, said Turvey. “Keeping real rates low has resulted in significant imbalances in the Turkish economy and inflation appears increasingly unanchored from the Central Bank’s target.”

Isaah Mhlanga, Rand Merchant Bank economist, said Turkey has also been disproportionately affected because of its large funding needs. “Because Turkey has significant external debt, which is coming due, the reversal of capital inflows seen in April and month to date in May implies they didn’t have enough funding to pay it. They haven’t been able to attract capital inflows. People did not view the rate at the time enough to justify putting money into the economy.”

To fund its needs and, critically, to stop the currency from sliding, Turkey had no choice but to hike rates. This week, the Central Bank also moved to simplify a notoriously complex system of multiples rates it uses. Capital Economics believes there is more to the simplification than meets the eye. (See “Central Bank leaves back door open”)

The interventions have helped. The lira bounced back to 4.50 to the dollar this week, although it is still under pressure.

Mhlanga said it was a short-term reprieve. “Sooner or later investors are going to require more if there is no change [in the economic fundamentals].”

Although all emerging markets will feel the pain of rising interest rates in the US, one cannot lump South Africa with Turkey, he said. South Africa’s macroeconomic environment is stable and there is no political investment in how it runs its affairs.

But, in both South Africa and Turkey, the question of Central Bank independence weighs on their economies. The South African Reserve Bank and Turkey’s Central Bank are part of an elite club — two of six in the world that are privately owned.

In South Africa, the ANC resolved to nationalise the Reserve Bank at its national conference in December last year. On Tuesday, it announced its national executive committee has tasked its economic transformation subcommittee to begin a process to produce models for nationalising the Reserve Bank. Although this has sparked concerns about the bank’s independence, it’s anticipated that changing the ownership structure will not affect the bank’s mandate but it would be a costly exercise.

In Turkey, although privately owned, the independence of the Central Bank, as evidenced by artificially low rates, is seen to be compromised. Erdogan has continually criticised its handling of monetary policy and urged it to keep rates low.

In May this year, Erdogan alarmed markets when he told Bloomberg TV he planned to play a greater role in setting monetary policy.

It goes to show, Mhlanga said, “the ownership structure means nothing. Politicians can always have influence.”

Tuvey said Erdogan’s view on rates and inflation may stem from advanced economies having low inflation and low interest rates.

“He has seemingly got confused with the way that the causality runs. Rather than low interest rates being the consequence of low inflation — as economic orthodoxy would suggest — he thinks that low inflation is the result of low interest rates.”

Central Bank leaves back door open

“Turkey’s monetary policy framework is notoriously complicated,” said Jason Tuvey, an analyst at Capital Economics, a London-based independent research consultancy.

The Central Bank of Turkey has three rates at its disposal to provide liquidity to banks: the overnight lending rate, the one-week repo rate and the late liquidity window rate, he explained. “The importance of each of these has varied over time. Since early 2017, only the late liquidity rate has been used and thus that has been the main determinant of local monetary conditions.”

For example, the key policy rate is meant to be the one-week repo rate, which is set at 8%. But it was the late liquidity window rate that was hiked to 16.5% in an emergency meeting last week in a bid to support the sliding currency.

This week it was announced that, to simplify matters, in June the one-week repo rate will be adjusted to the late liquidity window rate of 16.5%, which will be the single rate used to set policy.

But Tuvey says there may be more to the matter than meets the eye. In an investor’s note this week, Capital Economics said the decision would appear to be less like an effort to simplify its monetary policy framework than “a way to create room to raise market interest rates if necessary without incurring the wrath of President [Recep Tayyip] Erdogan”.

The Central Bank committed to using a single policy interest rate in 2014 but, by the end of 2016, it was once again using multiple facilities to provide liquidity to banks.

This time, again, the Central Bank still has the same number of interest rates at its disposal. It has also failed to confirm whether it will provide all of the banking sector’s liquidity needs by using the one-week repo facility.

“As things stand, it has left open the possibility of providing additional funding to banks at the overnight lending rate [which is now set at 18%] and possibly the late liquidity rate,” Capital Economics said.

“In other words, the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey has left itself with wiggle room to tighten monetary conditions without making an explicit change to the one-week repo rate.” — Lisa Steyn