Artist ruby onyinyechi amanze’s presence recalls the shape-shifting burlesque dancer played by Rihanna in Luc Besson’s recent 28th-century intergalactic escapade Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets

In her current exhibition, there are even moonbeams we can unfold, ruby onyinyechi amanze invites viewers into a speculative universe inhabited by “a cohort of beings who move freely through it”.

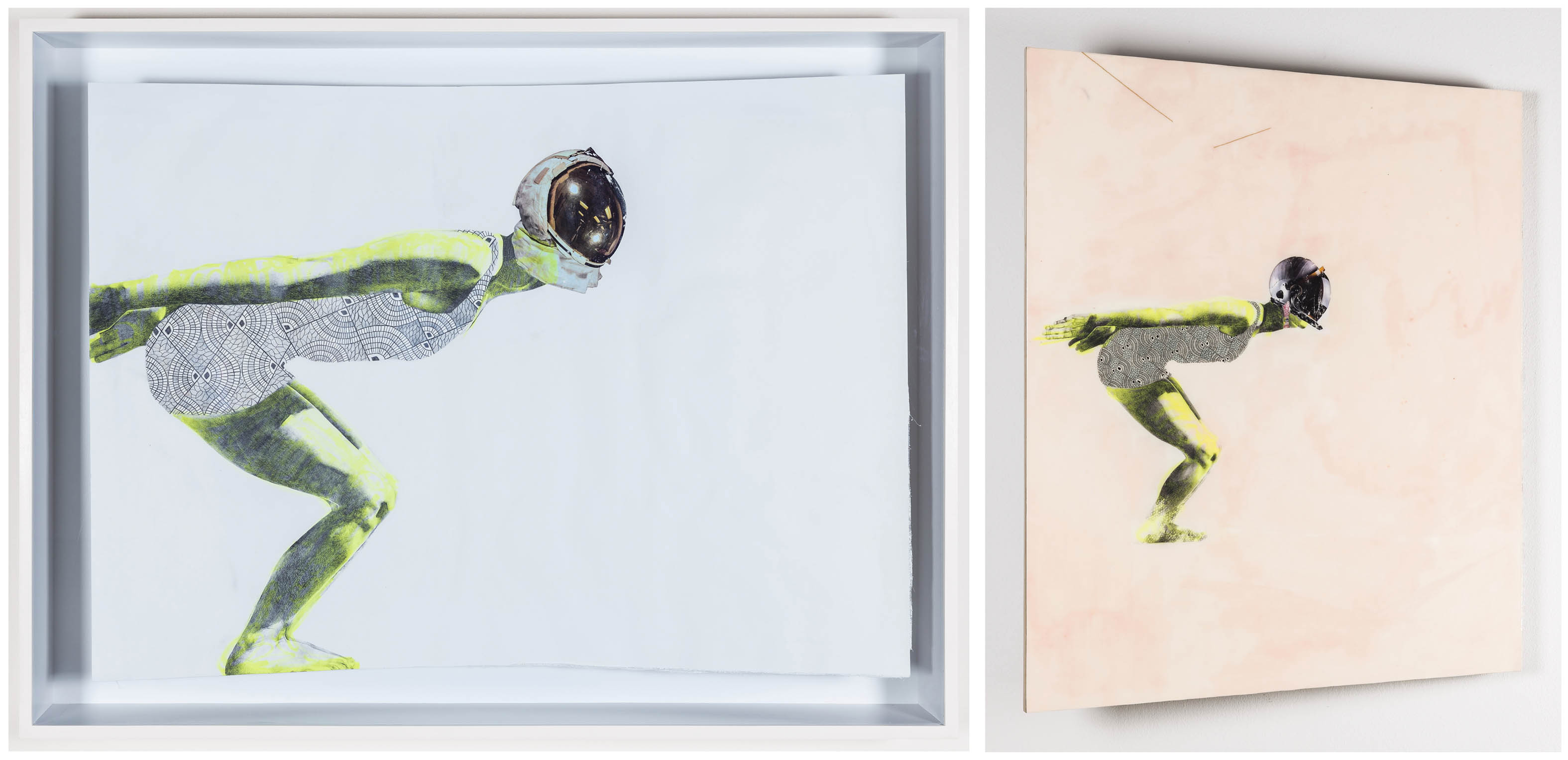

Her visual grammar of motorbikes, astronaut helmets, pot plants, birds in flight and greener-than-green AstroTurf conveys a sense of fluidity and mobility, which is ironic bearing in mind our world of militarised borders entrenching increasingly paranoid forms of hypervigilant nationalism.

This show is comprised largely of new work, as well as several works on paper that amanze produced during a 2016-2017 residency at the Drawing Centre, New York. Most of her drawings are large-scale, airy vistas you could float about in or inhabit. So it’s not surprising that she does physically occupy them for days or weeks at a time.

[Mythical characters: ruby onyinyechi amanze’s Untitled (diver)]

“The larger works are all done on the floor, which is generally too hard, so I build a new floor for them. It’s important for me to be inside the drawing, enter it and live in it for a bit,” she says. “I try to make a surface that’s hard and smooth enough to make a mark, but that also has some give. And I have pillows … I’m conscious to not leave a footprint but at the same time things shuffle, my elbow might indent the paper a little bit or I clumsily/dangerously have cups of tea. So things do happen. I can’t have spent hours and days and weeks in that world without it remembering some of the things that happened.”

She lives and works between New York and Philadelphia and, though she loves them both, is attached to neither.

Pristine and detailed, her figurative drawings are animated by a fantastical, chimerical cast of characters who seem to have emerged from the worlds of dream, legend and literature.

“It could be my person, or another individual who has inspired a character,” she says. Born in Nigeria in 1982, amanze has a strikingly millennial energy about her. Her vocal tones are tinged with a subtle tinsel timbre and her presence recalls the shape-shifting burlesque dancer played by Rihanna in Luc Besson’s recent 28th-century intergalactic escapade Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets.

“Mythology plays a role for sure,” she says. “I’m thinking of Merman as this character who is connected to water as location as opposed to land as location. That probably came out of acknowledging my mother’s history of being from Rivers State in Nigeria and being part of a cluster of ethnic groups in that region that I identify as being riverine people.

“So I’m looking at the different ethnic mythologies around water spirits and beings that dwell in or are charged by the water that is as much a location as land and sky.”

There is an architectonic aspect to amanze’s drawings and to the exhibition itself. There are framed and unframed works, naked paper works that scroll down from the ceiling. The corner of the page has been cut away or the frame itself has been recast, pushing the standard rectangular frame into a planar geometric logic that has more in common with 3D origami constructions.

In one work, the image of a flock of birds in flight appears on a folded white plane that recalls paper wings in flight or a computer-aided design drawing of the neofuturistic TWA Flight Centre building at JFK International Airport designed by Finnish-American architect Eero Saarinen.

Her titles are poetic, adding a narrative dimension to the drawings. Titles from previous exhibitions include: with the galaxy beneath her, she remembered soaring amidst coconut clouds, garden palace and the folly of innocence, 10 litres of air or, simply, kindred.

One work, made in 2015, is titled The Gift (a room of our own), which could be read as a riff on the title of Virginia Woolf’s seminal feminist text but introduces the multiple subjectivity imported into contemporary feminism with the transgender movement’s use of the plural possessive pronoun “they” (as opposed to the gendered binary her/his).

Woolf argues for both a literal and a figurative space for women artists in a literary tradition dominated by men. Similarly, amanze’s work asserts a literal, spatial, sensual and embodied kind of freedom — but she does so using paper, the medium of textual, intellectual assertions of power.

The show takes its title from a poem by André Breton that speaks to the poetic fluidity of space. A feeling of weightlessness and flight permeates the figurative scenarios she depicts, which seem to unfold in a zero-gravity field, like everyday astronauts inhabiting the International Space Station. But unlike the blockbuster spectacles that define the American sci-fi film idiom (dominated by a fixation with firepower, war and the military industrial complex), amanze’s futurist fictions are laced with a prosaic, everyday aspect, which is by no means incidental.

The everywhere/nowhere sense of malleable geography and space in her work is in stark contrast to the increasingly policed state of hyper-restrictive border control that is President Donald Trump’s United States. Some might perceive this as a failure, but I would argue that the politics of refusal or negation in her work claim space for a reality outside the reach of Trump’s divisive spatial politics and violent “grab-’em-by-the pussy” vocabulary.

“There is something about allowing for a difference of voices. There is the voice that is required at some points to be loud and charged in a particular way, but equally as powerful is nuance, subtlety and observation … That’s not a weakness in the sense of being fragile, or not wanting to make a statement, or not having anything to say. It’s quite the opposite, especially as a woman and as a black person.

“I have no obligation to be rah-rah. There can be a certain expectation to bedazzle that, for me, is problematic. There has to be room for other types of insertion or assertion. If I’m being honest and true, the way that I’m drawing it, the way that my person is in the world is what you’re seeing.”

Her work dares to enunciate a post-patriarchial world by means of a soft-core agenda. The sensuousness of her drawings recalls the aesthetic of Sofia Coppola’s 1999 debut film Virgin Suicides but amanze takes it forward with an intersectional transgender/trans-species outlook.

A human leopard figure appears repeatedly, asserting a speculative interspecies future.

“Their full name is Audre the Leopard,” she explains, “and they always present as male and as animal or beast amongst these other beings who are less immediately aggressive. Yet Leopard is in many ways the most tender of all of them. Their relationship with Ada and the other characters has often been one of protection and comfort. They hold everybody together in a gentle way.

“My characters tend to be gender fluid or gender neutral and they interact with each other from a place of intimacy and vulnerability. Wherever they are in this universe, they care for each other and recognise each other as a family unit of some sort.”

Grey, graphite tones are offset by washes of chartreuse and pink infused with glitter and iridescent ink.

“If I were to describe pink as a child there would only have been two or three types — baby pink, magenta pink … I can’t say that I was a pink lover but in recent years, and in my work specifically, it’s come to play a central role. It’s a colour that I gravitate towards.

“One inspiration for that is working with a friend who has a performance group and is doing this tetralogy of performances where each year is a different colour. The year that I worked with her was the year of pink, and we had a lot of conversations about what that colour is.

“In the way that I use it in the work, it’s moved past its association with femininity and softness. Pink now has a lot of character, strength and nuance to it. The scope of where we see pink in terms of design and art and fashion has widened significantly, breaking down its mono feel. There’s something about it that is very charged and present, but not in a way that is intended to intimidate aggressively. I’m really interested in the fact that a colour can do that.”

there are even moonbeams we can unfold runs at Goodman Gallery Cape Town until June 16