Patron saint: Randlord Sir Lionel Phillips and Lady Florence had their portraits painted by Giovanni Boldini. A smaller version of Portrait of Lady Phillips is in the South African National Gallery

Centuries ago, a lucrative culture of buying art was established. Rich people began buying art for three reasons: it looks beautiful, it makes money while it rests in their homes and buying art is something that other rich people do.

Within this buying practice there are two types of collectors: those who have a relationship with the artist, such as Peggy Guggenheim in the 1930s and those who rarely interact with artists such as in the 16th to 18th centuries when royal museums and Wunderkammern were established. These practices existed then and today continue in a way that creates a particular pattern of preservation in the art world.

1434-1737: Medicis set a trend

The idea of buying art in batches was derived from the habit of the powerful Italian family, the Medicis. During the Renaissance era, the Medicis collected works by emerging artists and provided them with resources to create and develop their skills.

The Medicis influenced the direction of the Renaissance because under their rule Florence attracted intellectuals and artists who sought the family’s financial backing.

In 1765, shortly after the family’s reign ended, its art collection was given to the city of Florence by the last heiress of the Medicis, Anna Maria Luisa. It’s still available for public viewing.

During the Industrial Revolution (from about 1760 to between 1820 and 1840) collecting expensive possessions became a symbol of status.

1860s: The birth of Kimberley

Michael Stevenson, gallerist and author of Art & Aspirations: The Randlords of South Africa and Their Collections, writes about how men who built their fortunes from Kimberley’s diamond fields “acquired and displayed properties and possessions that symbolised wealth and power in Europe”.

It began in 1866, on the banks of the Orange and Vaal rivers, when a boy, Erasmus Jacobs, found a glistening pebble. The children used to play with it but later he showed it to his father, who gave it to a neighbour, who gave it to his friend John Robert O’Reilly. He sent it to a geologist who determined it was a diamond.

News of this valuable stone found in the muddled area bordering the Cape Colony, the Griqua states and the Orange Free State started a hungry hunt for places that had more stones. Diamonds were found on two farms, Bultfontein and Dutoitspan, and attracted thousands of hopeful diggers. By 1872, the settlement’s population had grown to 50 000 people. Their makeshift houses, tents, shovels and home-made strainers formed an industrial community — hello, Kimberley!

1870s: Get rich. Quick

When the news of Boers benefiting from a rapidly growing mining industry (first diamonds and later gold) reached Europe, fortune-seekers sniffed an opportunity to get a piece of the mining pie. With bags and wives in hand, they bade their lives goodbye and boarded ships to Africa with the hope of becoming rich.

Upon arrival in South Africa, the fortune-seekers formed stokvel-like alliances to purchase mining property. Once the land was theirs, they registered it under one fortune-seeker’s name and the rest were listed as investors with shares in the property.

But there was the predicament of needing more money to run a mine. To solve this, mining properties were listed as stock for the public to invest in and earn dividends. The public eagerly bit the bait but were bamboozled by the stokvelites. The dividends the public investors received were only calculated once initial shareholders who co-owned the mining property had received most of the profits. Their cunning efforts were generally a success.

1880s: Migrant labour

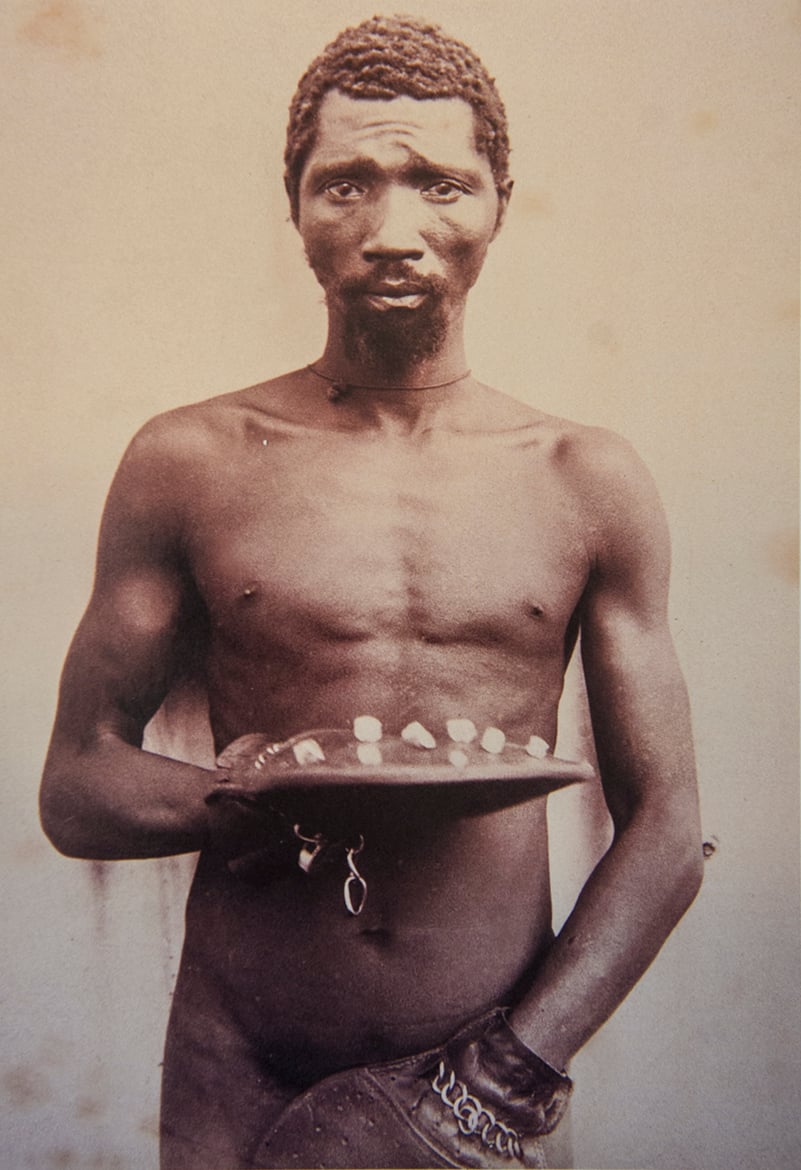

[Cruel gems: In the 1870s, about 50 000 black migrants worked on the diamond fields each year. They were strip searched at the end of every day. When their contracts ended, they were held naked in detention houses until they had excreted diamonds they might have swallowed. (Photo: Art & Aspirations: The Randlords of South Africa and their Collections by Michael Stevenson)]

As Kimberley grew, life for many Africans changed because of the increased demand for labour to mine diamonds. Operational costs had to be reduced to the bare minimum for profits to be maximised. The call for cheap labour was answered by migrant workers from across Southern Africa, increasing when gold was discovered — first on Vogelstruisfontein in 1884 and in 1886 on the farm Langlaagte. Unknowingly, the labour of aboMalume noobhuti would lead to the enrichment of the European settlers who poured into the Boer republics. The Randlords, and Britain’s desire to expand its empire, resulted in the disastrous Jameson Raid and two wars between the Boers and the British.

1880s-1890s: Randlords head to Europe with buying power

Not too long after arriving in the mining landscape, about two dozen fortune-seekers made fortunes that continue to benefit their offspring today. Many of them retired to Park Lane, London, which was characterised by old money, as a first step in declaring themselves part of Britain’s elite. They filled their mansions with high-end possessions that emulated the look and feel of wealth. One significant trick they used to do this was to aggressively buy art, because of the status associated with collecting it, which they desperately wanted. The title Randlords is derived from how their wealth was earned — gold mining in the Witwatersrand.

The Randlords arrived in Britain just as the aristocrats were adjusting to the decline in land value under the Settled Lands Act of 1882 and 1884. Before this period wealth was linked to land ownership but the demise of agriculture caused the value of land to drop. To meet tax demands, the rich sold their art rather than their land. Art became more valuable than land, because its value was readily realised by asset assessors. Randlords quickly bought up respected artworks by the “old masters” (Da Vinci and Michelangelo, among others) to create enviable collections.

Some of the Randlords with notable art collections included Sir Joseph Robinson, Sir Lionel and Lady Florence Phillips, Sir Max Michaelis, Sir Otto Beit and Sir Julius Wernher.

1900s: Giving back a pinch of what they gorged

The negative perceptions of the Randlords living excessive lifestyles after stripping the colony of its minerals was exacerbated by the British upper class’s prejudice towards those from German or Jewish backgrounds. As outsiders, their efforts to fit into the upper class were rejected. To counter this, the Randlords set up donation channels back to the British colony.

Gifts of art became a part of the Randlords’ philanthropy, because it showed off their wealth. Randlords such as Alfred Beit, Wernher and Robinson had collections big enough to donate large sums while keeping plenty, and their collections remained in the possession of their families.

1910: We’re guilty, so here are art galleries

When critics took to the Twitter of their day — journals and newspapers — to comment on the lack of art in the Randlords’ charity, the concept of Johannesburg Art Gallery (JAG) emerged. Under the influence of his wife Lady Florence, Phillips persuaded his fellow Randlords to give gifts of artworks as a tangible way of returning some of the mining profits to the country, along with improving the presence of art in the union.

At first many of them refused to participate but, after some time, a few followed suit. First Sir Abe Bailey gave his collection of art on permanent loan to the South African National Gallery in Cape Town. Then Lady Michaelis returned to South Africa after her husband Max’s death to present the majority of the Michaelis collection to the National Art Gallery. Yes, this is where the University of Cape Town’s Michaelis Art School derives its name from.

Part 2: The rise of the museum to showcase art collections

1889: Henry Tate

Henry Tate made his fortune as a sugar refiner in the 1800s. A large chunk of his earnings went towards assembling an art collection. In 1889 he offered this collection to Britain’s National Gallery. The gallery’s trustees say “no thanks”, because his collection was too big for the gallery.

So, he rallied his peers to create a gallery dedicated to British art. With an initial amount of £80 000, a gallery at Millbank was built to house works from the National Gallery along with Tate’s collection. Tate Britain went on beget the Tate Modern, Tate Liverpool and Tate St Ives.

1889 – 2018: Art and the Henri Pinaults of the world

Lady Phillips appeared to be doing the noble thing by donating JAG’s founding collection but she reaped major money when an even larger part of her family’s collection was sold to the world’s leading auction house, Christie’s. Other Randlords put their large art collections up for sale at the auction house. Today Christie’s is largely owned by Groupe Artémis, which also owns Balenciaga, Gucci, Stella McCartney and many other subsidiaries, including the lifestyle brand Puma.

The chief executive is François-Henri Pinault; the company was started by his father François. To date Artémis has the world’s largest art collection housed in buildings in Venice for the public to view.

This is pretty standard business practice: get rich, buy art, let it sit and accumulate value over time, charge the public to see it in a nice building.

As an institution, the museum is different from the model of a foundation in that the title suggests that there is an association with public interest and the state, whereas foundations can exist with the sole purpose of showcasing collections.

One example is the Rubell family collection, showcased in Miami at the Rubell Family Collection and Contemporary Arts Foundation, where 6 800 works of art by 831 artists are on display.

The Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris, owned by the archrival of Pinault, the LVMH group headed by Bernard Arnault, also has an art museum dedicated to the preservation and collection of art.

Closer to home were art financiers and collectors such as Piet Viljoen, who with his collection established the New Church museum in 2012, positioned as a museum dedicated to showing his collection. A similar institution, the Norval Foundation, opened last month in Steenberg, Cape Town.

Current: The saga continues at Zeitz Mocaa

German businessman Jochen Zeitz, former chief executive of Puma and the co-owner of Richard Branson’s The B-Team, is said to be the largest collector of contemporary African art. Last year, the public display cabinet for his amazing collection, Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa, opened its doors on Cape Town’s V&A Waterfront under the direction of buyer and now former chief curator, Mark Coetzee, who held several senior positions at Puma’s CSR divisions and was a former director of the Rubell family collection.