What happened to the once universally accepted idea of healthcare for all?

For health workers, life and death decisions are just a part of the job. But long hours, heartbreaking cases and tough working conditions can take their toll — and medicine still isn’t talking about mental health when it comes it its own.

Stellenbosch University journalism professor Lizette Rabe’s son, a medical student, had plans of getting his own apartment and a dog when she lost him to suicide.

“Ten days before his death, I still had to buy him not one, but two pairs of the shoes he liked wearing in hospital. He was to do his fourth-year internship, at the end of the academic year, at a mission hospital in Tanzania”, Rabe told Bhekisisa in 2017.

Rabe later set out to destigmatise the way suicide is spoken about, changing the way many South African media outlets report on suicide. Now, some organisations have adopted the phrase “died of suicide” — much like people die of cancer — instead of the more stigmatising term “committed suicide”. This move was particularly important for Afrikaans-language outlets, the term often used for suicide is “selfmoord”, which directly translated into English is “self-murder”.

South Africa may be slowly changing the way it speaks about suicide but mental health issues among medical professionals rarely make the headlines — in the news or in research.

A 2018 international research review found Free State nurses had the highest documented prevalence (at least 98%) of emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation — or having unfeeling and impersonal responses towards patients. These figures dated back to a 2008 study published in the South African Journal of Economics, noted the systematic review published on the website, Gates Open Research. The site is a peer-reviewed, open access portal for research funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Although research into burnout was common in higher income countries, authors said there is a dearth of similar studies from middle- and especially low-income countries.

A smaller but more recent study conducted among about 70 North West doctors found that more than a quarter reported being so stressed that they were at risk of burnout or depression, argued 2012 research published in the South African Journal of Psychiatry.

Statistics such as these are why a group of Australian doctors came up with an annual campaign — and hashtag #CrazySocks4Docs — to let doctors battling with mental health issues know they weren’t alone. Since then, doctors across the globe wear colourful, silly socks to show their solidarity

The campaign has gone global from Malawi…

To Ga-rankuwa.

So here are five hard truths we learned from this year’s fancy footwear.

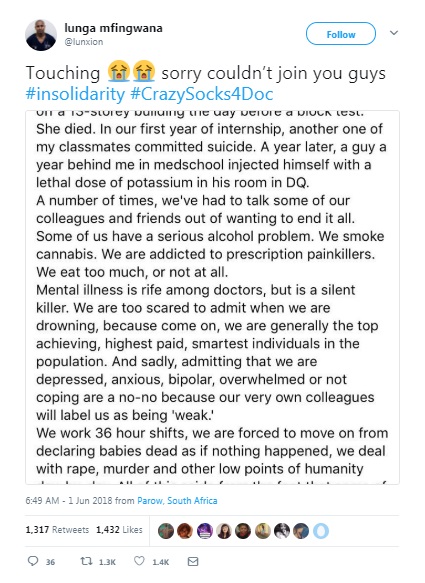

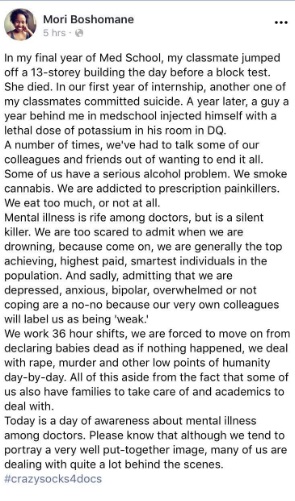

1. Healthcare workers know that we all expect them to be everyday superheroes all the time and keeping up appearances isn’t easy.

See the Facebook post here:

2. Healthcare workers are human — just like everyone else.

3. And, no, years of medical school doesn’t prepare you for everything.

4. Mental health matters just like any other aspect of your health. So floss and hit up your psychologist.

5. No matter how dark the situation, there’s always help.

Do you or someone you know need help? Contact the South African Depression and Anxiety Group on their 24-hour helpline on 0800 12 13 14. And in the event of a suicide emergency, contact them on 0800 567 567. Medical students in need of help can contact the Discovery Medical Student helpline on 0800 323 323.