Divide: Emotions ran high at the public hearings into expropriation without compensation in Limpopo.

Songstress Letta Mbulu’s 1990s hit Not Yet Uhuru playing softly on the PA system during lunch at the Marble Hall Town Hall summed up the views expressed by many people during public hearings into proposed changes to section 25 of the Constitution.

The Limpopo leg of the hearings got under way in the farming town on Wednesday. A huge crowd of mainly young and old people packed the hall. Others had to be accommodated in a tent in the grounds.

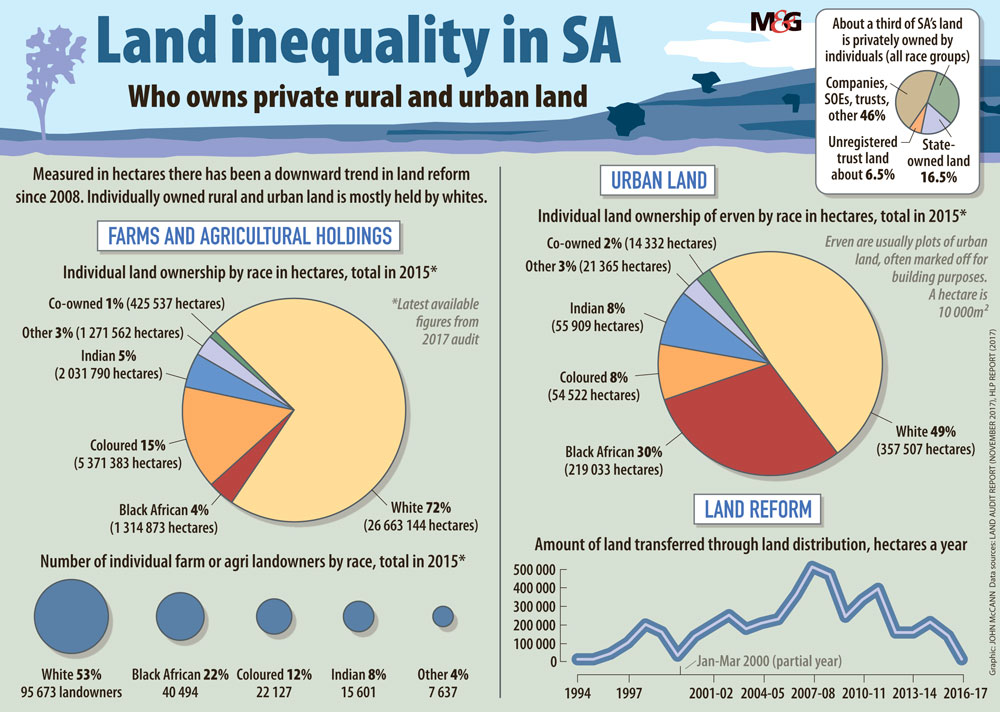

If anything, the hearings brought to the fore the deep-seated anger and desperation felt by black people, many of whom expressed resentment about their privileged white compatriots’ continued hold on most of the land.

On the other hand, whites used the platform to express their fear and uncertainty about what they believe will lead to loss of individual property rights and threaten food and job security in the agricultural sector.

“If you take away my farm, I lose my work, my house, my pension,” said a man, expressing the fears of his fellow white farmers.

One farmer, who introduced himself only as Malan, blamed the government for failing to implement the constitutional requirements to speed up land reform, arguing that section 25 should not be changed because it did not impede land restitution and reform.

READ MORE: Emotions run high at Northern Cape’s first hearing on land expropriation

Michiel Pretorius, dressed in the traditional farmer’s uniform of khaki shirts, shorts and woollen socks stood nervously outside the hall flanked by his family. He works on a farm in Marble Hall, which employs more than 500 people, the majority of whom are black. He farms 360 hectares of citrus fruit, 120 hectares of cotton and 60 hectares of grapes. He also fears losing his farm and blames the government and political parties for trying to win votes by stirring up emotions about the land issue.

Pretorius says that, although there is fear among his colleagues, he has heard no talk of bloodshed and he is not thinking of leaving the country, regardless of the outcome of the land debate. “This is South Africa. I was born here. I have lived here all my life. I am not going to leave.”

Black people vented their anger and despair about still not having land — but also about issues of unemployment, unfair treatment by farmers and sewage in the streets. (Lucas Ledwaba/Mukurukuru Media)

Black people vented their anger and despair about still not having land — but also about issues of unemployment, unfair treatment by farmers and sewage in the streets. (Lucas Ledwaba/Mukurukuru Media)

Elias Makofane, who introduced himself as “a military veteran without a piece of land”, said Parliament should try to address the fears of white people, arguing that they were not necessarily opposed to the proposed amendment but were afraid because there were no guarantees that their land will not be expropriated without compensation.

“Let us share [the land],” he said.

In the main, the hearings exposed the deep racial divide that continues to simmer on the ground, especially around farming towns such as Marble Hall.

It also exposed the indifferent attitudes of white people to acknowledge what President Cyril Ramaphosa defined as “the original sin” of land dispossession.

READ MORE: How land expropriation would work

“Parliament must tell us, when are you arresting them [white people] or when are they leaving?” Johannes Tshego said in his submission to roars of approval from the crowd made up mainly of black people.

But it appeared that many did not understand the purpose of the hearings. Some people vented their feelings about a wide range of issues, including unemployment, employers who locked up workers in factories, a son fired from his job at a furniture shop, and a settlement whose streets are flowing with raw sewage.

Uncertainty: The public hearings into proposed amendments to the Constitution to allow for expropriation of land without compensation have exposed the fears of white farmers. (Lucas Ledwaba/Mukurukuru Media)

Uncertainty: The public hearings into proposed amendments to the Constitution to allow for expropriation of land without compensation have exposed the fears of white farmers. (Lucas Ledwaba/Mukurukuru Media)

Committee chairperson Vincent Smith had a difficult task to maintain order, reprimanding those who booed at mention of the proposed changes and used inflammatory language. But more than that, he was pushed to keep reminding the audience that their submissions should answer the question on whether section 25 needed to be changed.

Seemingly frustrated by some of the submissions, Smith told the Mail & Guardian that the committee had made efforts to educate people about the purpose of the hearings. He said they had sent advance teams to explain the submission process.

The town boasts a thriving agricultural sector. Cotton, citrus and tobacco are the main crops. The vast majority of farmers and owners of commercial land are white people, and the majority of black people are crammed into informal settlements and tribal trust land surrounding the town.

Echoing Mbulu’s lyrics that nothing has changed materially for black people, most of the participants explained that they lived in shacks and had no access to land. People and nongovernmental organisation representatives drew attention to the skewed patterns of land ownership.

Vasco Mabunda, of the Nkuzi Development Association, warned that there would be no peace in the country if the land issue was not addressed.

In Mokopane, on Thursday, thousands of people packed the Ayob Toob Hall to express their feelings. Long queues formed as early as 8am for people to register and enter the hall. Proceedings were slightly delayed when the hall was full and those left outside tried to force their way in.

The racial economic divide was clearly apparent, with scores of black people arriving in buses and minibuses, whereas the dozens of white farmers turned up in their 4x4s.

Speaking in Afrikaans, Valerie Byleveldt threatened “the biggest revolution South Africa would ever see” if Parliament went ahead with the constitutional changes. And Morné Mostert of minority rights groupAfriForum laid the blame at government’s door, saying it owned a great deal of land but was unable to distribute it adequately.