(John McCann)

South African mining stocks lost R50-billion after the first draft of Mining Charter III was published in June last year.

A year later, the sector’s reaction to the 2018 draft under Mineral Resources Minister Gwede Mantashe hasn’t been as dramatic but there are still rumblings that it will make the sector uncompetitive and unattractive.

Mantashe has the unenviable task of trying to balance transformation goals with the need to promote investment in an industry that has been in decline for several years.

But when South Africa is weighed against other mining countries on the continent, all is not gloom and doom.

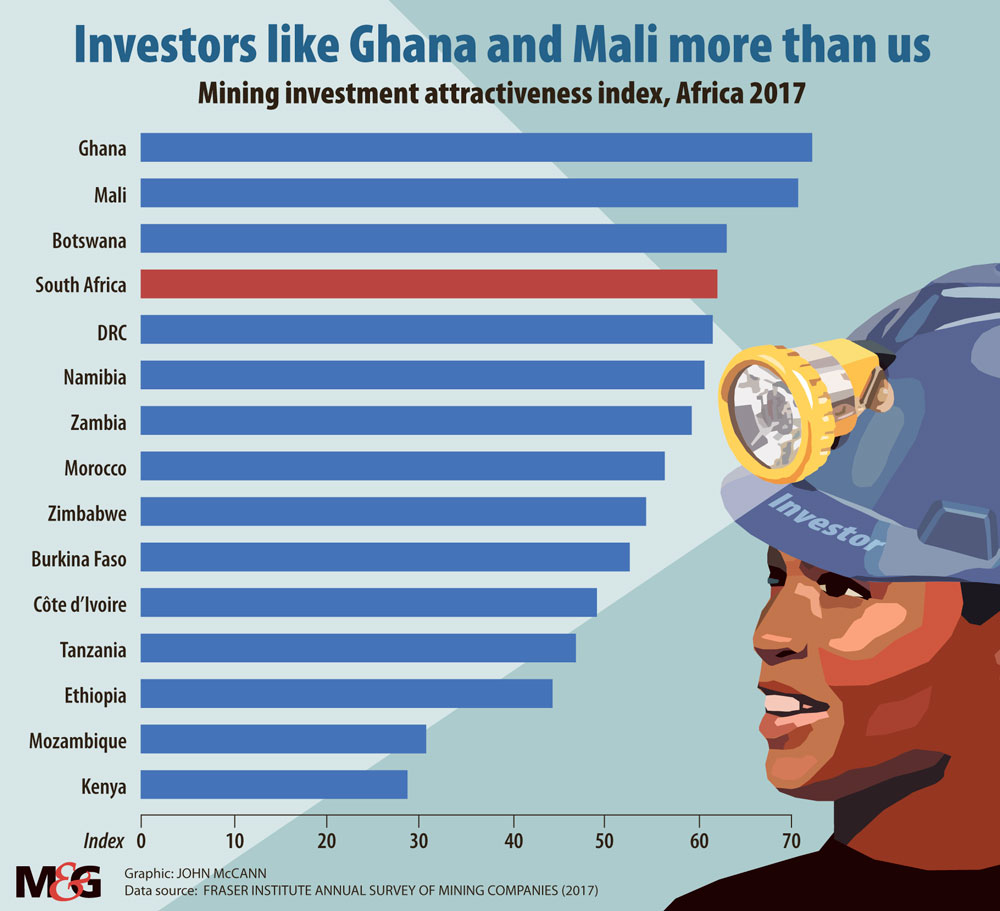

According to the Fraser Institute’s annual mining survey for 2017, on the policy perception index (PPI), South Africa is ranked at 13 out of 15 African countries.

The index rates the attractiveness of mining policies according to issues such as security, uncertainty, political stability and uncertainty concerning disputed land claims. The institute describes it as a report card on how attractive government policies are from an exploration manager’s point of view and it usually accounts for 40% of an investment decision. The other 60% is based on a country’s mining potential.

But in terms of overall investor attractiveness, South Africa ranks relatively high on the continent. On the investment attractiveness index, a combination of PPI and mining potential, South Africa is at number four, behind Botswana, Mali and Ghana.

“South Africa has one of the most developed financial markets on the continent, from the capital market to the banking sector. It has the best national infrastructure in Africa and is one of the most developed economies. We also have one of the largest, diversified deposits of minerals anywhere in the world,” said Peter Leyden, a director at law firm Herbert Smith Freehills.

“The question becomes, what is the issue that is preventing South Africa from being one of the top mining destinations in the world? The problem is the [policy and regulation] uncertainty we have had.”

The new draft of the mining charter is a step towards certainty and makes several concessions on controversial issues introduced by Mantashe’s predecessor, Mosebenzi Zwane.

The charter recognises the once-empowered, always-empowered clause, so any mining company that reached the 2010 charter’s 26% black economic empowerment (BEE) target is compliant. But it still proposes an increase of the BEE shareholding to 30% for new mining projects and gives mining companies with existing rights five years to raise their BEE level to 30%.

The clause was a feature in the 2004 and 2010 charters.

The Minerals Council, which represents 90% of the mining companies in South Africa, said it did not support this because it “prejudices existing rights holders that secured their rights on the basis of the 2004 and 2010 charters”.

The council found it disappointing that the draft did not allow its requirements for junior and emerging mining companies to be phased in, which would curtail exploration, the lifeblood of the industry, it said.

Another condition that would deter new mining investment is the 5% free carried interest for mining communities and employees. That means 10% of the mining shareholding will be given to the respective parties, besides a 1% of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation dividend for communities and workers if a mine fails to pay dividends in the first five years.

Several other countries on the continent insist on free carried interest. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), one of the world’s largest producers of cobalt, which also mines diamonds and copper, has a free carried interest condition of 5%, and Mali and Tanzania have between 10% and 16%.

Leyden said that, although South Africa’s charter might not be as onerous as Tanzania’s or the DRC’s, there was still a need to make the sector more attractive to investors.

“For South Africa, we have a very developed mining industry, so there’s not a lot of excitement [compared with] other jurisdictions, where it’s a bit underdeveloped. You have countries like Ghana and even Zimbabwe where there is potential for new discoveries and projects.”

In a bid to attract investment, diamond and uranium producer Namibia said it was planning to do away with its black ownership requirement in the mining sector. The country’s mines minister was quoted by Reuters as saying that giving exploration licences to people who didn’t add value would slow down black empowerment.

The Fraser Institute said that, when policies were considered, Namibia was the second-most attractive jurisdiction on the continent. It is ranked at 39 globally.

For its policies, Botswana came in at number one on the continent and at 21 out of 91 countries. Leyden said that was because the diamond producer had had the same mining codes since 2001, with very few amendments.

“Investors need to know that, if they put the money in on day one and they build their financial model, the regulatory regime and requirements are going to be stable in the life of their project. The first thing we need to do is get a stable, clear and concise set of regulations and policies that create stability in the mining sector,” Leyden said.

Mining projects usually have long leases, often up to 30 years from initial exploration and production. South Africa has had three mining charters since 2004, and the Minerals and Petroleum Resources Development Amendment Bill has been waiting to be finalised since 2013.

Other transformation requirements that have come under scrutiny include stipulations that mining-rights holders must buy 80% of the services they need from South African companies, of which 70% must be black owned, and 70% of goods must be bought from South African manufacturers, of which 26% must come from 51% black-owned firms.

The charter is open for public comment for 30 days after its release on June 15. The department will hold a summit on July 7 and 8 for comment and to make “minor” changes before the charter goes to the Cabinet.

Tebogo Tshwane is an Adamela Trust financial reporter at the M&G