Like other survivors of Liberia's two civil wars

As Liberia appears before the UN Human Rights Committee in Geneva, Liberians ask why the government has failed to prosecute those responsible for atrocities committed during the country’s two civil wars.

Peterson Sonyah was only 16 years old when he sought refuge in St Peter’s Lutheran church on the outskirts of the Liberian capital, Monrovia. It was 1990, and Liberia’s first civil war had already been raging for a year. As rebels laid siege to Monrovia, an estimated 2 000 people crammed in the church, hoping to avoid the violence

Troops loyal to then president Samuel K. Doe broke into the church killing, raping, setting fires, and sparing only the lives of those able to bribe them. 600 people died.

“When the soldiers stormed the building, everyone was crying: men, women and children. They were killing innocent people. I lost my father, my uncle and my cousins, seven persons in all,” Sonyah recalled.

Like other survivors of Liberia’s two civil wars, which raged from 1989-1997 and 1999-2003, Peterson Sonyah is still waiting for justice.

“There is no way we can let those who committed heinous crimes against humanity go with impunity. I want justice because it will serve as a deterrent for others; I want justice because those who committed crimes and supported the war are around here living the best of lives, while those they victimized are going to bed on empty stomachs,” he told DW.

No reconciliation without justice

Four survivors of this particular massacre brought a suit in the US against Moses Thomas, a former colonel in the much-feared Special Anti-Terrorist Unit, whom they say gave the orders that night. Thomas now lives in the US state of Pennsylvania.

Hassan Bility, executive director of the Global Justice and Research Project, a Liberia-based non-profit, non-governmental organisation that documents war related crimes, blames the failure of Liberian governments to prosecute on a lack of political will.

“The most important things is that there is no statute of limitation. People want justice, even a very large number of people who voted for this government. The Liberian government does not have the power to ask anybody to forgive or forget,” he told DW.

Bility believes that true reconciliation in Liberia failed because it has not been built on a fundament of justice for those who suffered. But since the crimes are “international in nature,” prosecution is sure to happen whether in Liberia or not, he assured DW.

“We are not going to rest; we have the support of all of the countries in the world and all of the democracies on earth to do this,” he said.

Pressure from the international community

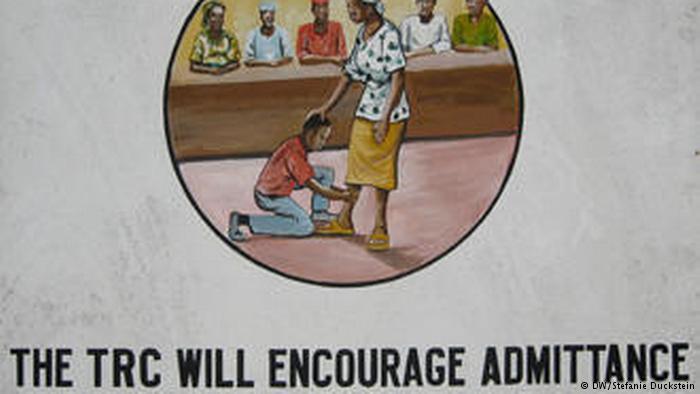

The international community has been increasing pressure on Liberia to implement the recommendations of the Liberian Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) dating back to 2009 and never acted upon. UN representatives are taking the government to task. Monrovian representatives were in Geneva on July 9 and 10 to answer questions by the UN Human Rights Committee on their lack of action. Meanwhile, 76 Liberian, African, and international non-governmental organisations have submitted a request to the UN to get Monrovia to do more.

The TRC was set up by President Sirleaf, but she failed to act upon its recommendations (DW)

The TRC, set up by former president Ellen Johnson Sirleaf to probe war crimes and rights abuses linked to Liberia’s conflicts, recommended the paying of compensation to victims and a special court set up to try the suspects, including eight identified warlords. An estimated 250 000 people died in the conflicts.

Hopes and doubts raised by the new president

Hassan Bility is optimistic concerning the will of current president, George Weah, to implement the TRC’s recommendations. The activist sees Weah as someone with “clean hands” who believes that people should be held accountable for their actions.

But Weah’s decision to choose as vice-president Jewel Howard Taylor, the ex-wife of former rebel leader and president Charles Taylor, is seen by many Liberians as a snub to the victims. In 2013 Taylor was sentenced to 50 years in prison by a UN-backed war crimes court. He was found guilty of aiding war crimes in neighboring Sierra Leone, but not of the recruitment of child soldiers, killings, rape and pillaging of which he is accused at home.

DW tried to reach government representatives to comment on its lack of action against perpetrators. Sylvester Pewee, Assistant Minister for Public Affairs at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs said that the government could not grant interviews while consultations were ongoing. — Evelyn Kpadeh contributed to this article.