We went after a trail left by Gupta lieutenant Salim Essa. What we found was a group of Jewish businessmen who complain of being shunned by their community because of their association with the Guptas.

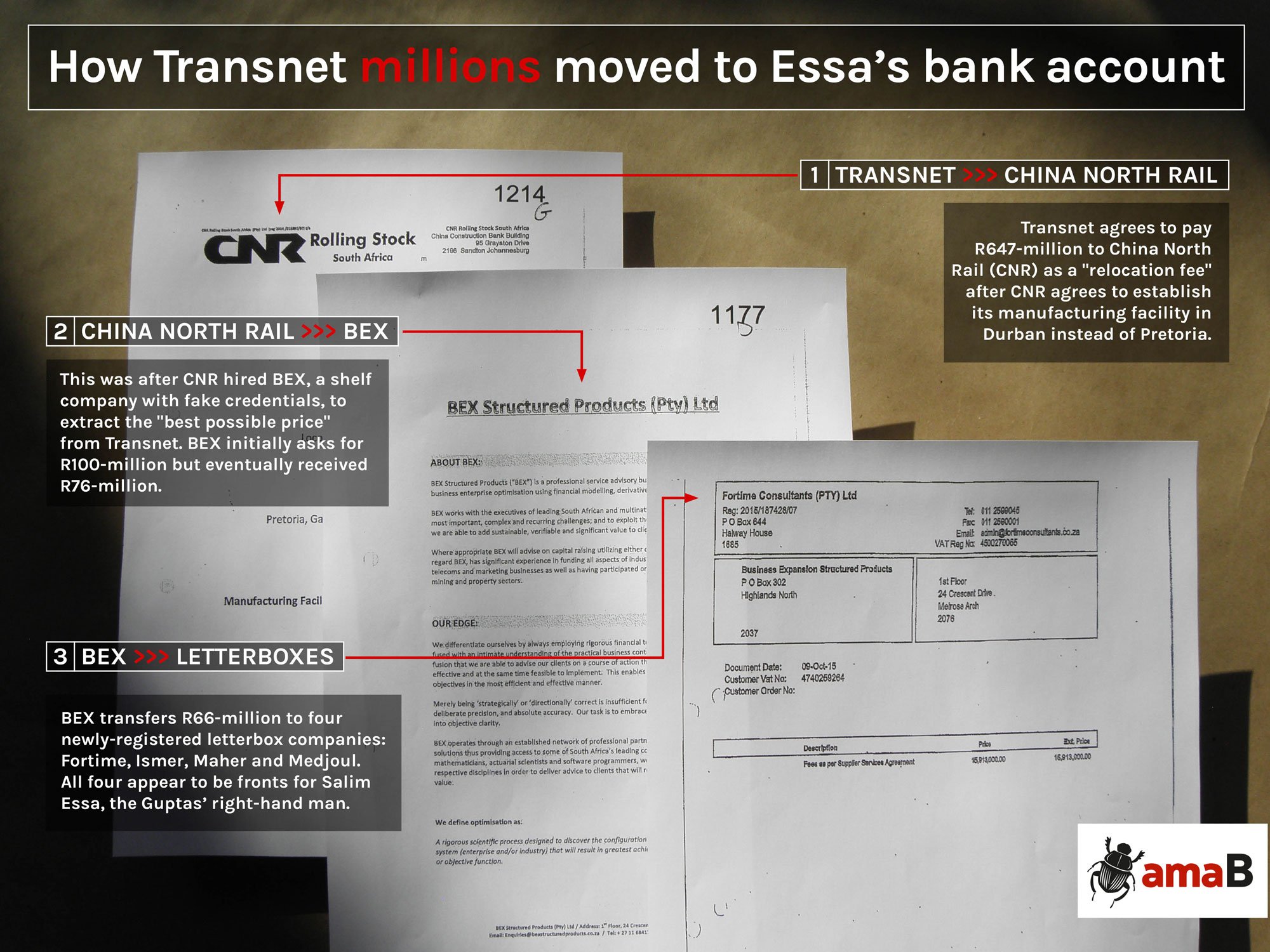

Our investigation suggests the community called it right. Essa extracted R76-million from a Transnet relocation project – but not without the assistance of a fake company with a stolen identity and a ghost director to help drive up the price Transnet was willing to pay.

The greed of a Chinese locomotive company has exposed the “Gupta minyan” – the memorable tag coined by members of the local Jewish community and first published in the SA Jewish Report.

A minyan, in Judaism, is the quorum of 10 men required for public prayer, but in the context of the Guptas it refers to a group of businessmen who allegedly formed a key Gupta brains-trust and worshiped, at least figuratively, at the Saxonwold ATM.

When SAJR wrote about them in November 2017, there was a certain diffidence.

“You all know at least five names that perhaps are linked to Trillian, Eskom, McKinsey and I could go on,” wrote editor Peta Krost-Maunder.

She noted: “I once suggested to a colleague of mine that there were two types of South African Jews, those who support the Gupta guys and those who don’t. He disagreed, saying there were no Jews supporting them. Only their closest family and friends are backing them, but for the most part we are unforgiving.”

Krost-Maunder concluded the community should suspend its judgement: “They are innocent until proven guilty!”

That stance is harder to maintain now that much of the “minyan” has gathered around the protective robes of Billy Gundelfinger, best known as a celebrity divorce lawyer, but also a go-to guy for criminal defence.

Gundelfinger is currently representing Selwyn Nathan, Clive Angel, Stanley Shane and Marc Chipkin.

Gundelfinger insists there is “absolutely no criminality on behalf of any of these parties… they were [merely] service providers”.

Bex: the sham behind the relocation scam

The reason for this nervous assembly is a strange little company called Business Expansion Structured Products – Bex for short – and its role in yet another Transnet rip-off orchestrated by Gupta minion Salim Essa– in this case on behalf of China North Rail (CNR).

AmaBhungane has already reported how CNR called in Bex – a shelf company that we linked to Essa – to extract R647-million from Transnet for changing the venue for local locomotive manufacture from Pretoria to Durban.

A report into Transnet by law firm Werksmans revealed that this was a project that, by one internal estimate, should have cost just R9-million.

Instead Bex promised to extract the “best possible price” from Transnet. Bex, a company with no track record, initially asked for a R100-million fee.

CNR, Werksmans found, eventually paid a commission of about R76-million to Bex for having secured payment R647-million from Transnet.

The R647-million was considered so excessive by CNR’s own local empowerment partners – and the payment to Bex so questionable – that they laid a charge with the police in terms of the Prevention and Combating of Corrupt Activities Act.

CNR’s South African auditors reported the payment as having “significantly misrepresented to Transnet the cost of the relocation” and later resigned.

The relocation project is currently “subject to a number of investigations by a number of law enforcement authorities in South Africa”, according to Transnet.

Behind the Bex façade: Respectable businessmen

Now amaBhungane has established that propping up Bex and Essa was a scaffolding involving two more substantial companies and other more established businessmen.

In following the clues left by Essa, we wound up at the doors of investment manager Integrated Capital Management (ICM) and corporate services firm Legal Frontiers, neither previously linked to Bex.

ICM was formerly chaired by Selwyn Nathan and at the time controlled by its three directors, Angel, Shane and Chipkin. These three men have previously been linked to Essa via their alleged role in the establishment of Trillian, the consultancy controlled by Essa that booked massive fees from Transnet and Eskom.

Legal Frontiers is co-owned by Wayne Tichauer, at whose accounting firm, Tichauer & Bloch, another important role-player works: auditor Mark Shaw.

This information did not emerge without a struggle.

Initially our questions were met with silence or evasion.

Then Gundelfinger and his legal partner, Kamal Natha, emerged to tender candour and co-operation on behalf of “our guys”.

The lawyers provided a detailed written version of events and complained that their clients were getting a bum rap; insisting they were merely the little fish who had innocently provided bona fide services to Essa, whom they believed to be a respectable businessman.

Then that version began unravelling. It happened like this.

The unravelling

The first two people we could identify behind Bex were Shaw and Taufique Hasware.

Public company records listed Shaw as a former co-director of Bex, together with Hasware, whom we had previously linked to shelf companies operating as “letterboxes” for the Guptas and Essa, passing back large “commissions” from Transnet contracts.

But when we first went to see Shaw, he seemed as puzzled as we were to be linked to a company that had received an alleged Gupta pay-off.

He said it was strange that he was registered as a director of the company – that was not normally the case with the shelf companies that Legal Frontiers sells.

Reporting back on her meeting with Shaw, amaBhungane’s Susan Comrie recounted: “He seemed genuinely perplexed by the whole thing. But he might be a good actor.”

Now we know that he is a good actor.

Shaw’s story collapsed as soon as we obtained access to the annexures to the Werksmans report. Handily, they included a copy of the commission agreement signed between CNR and Bex.

The document showed that, far from being uninvolved, Shaw had been the one who signed the contract with CNR on behalf of Bex.

We also established independently that Shaw had been the signatory to the Standard Bank account he opened in the name of Bex into which CNR had paid the commission.

So we went back to Shaw.

Susan again: “I told him we had the Werksmans annexures and he is mentioned… I then showed him the signature page of the Bex contract and he confirmed it was his signature.”

Shaw then explained he acted on behalf of a “client” he would not name.

Other threads of evidence, however, pointed to Shane and company: ICM in other words.

We got there this way.

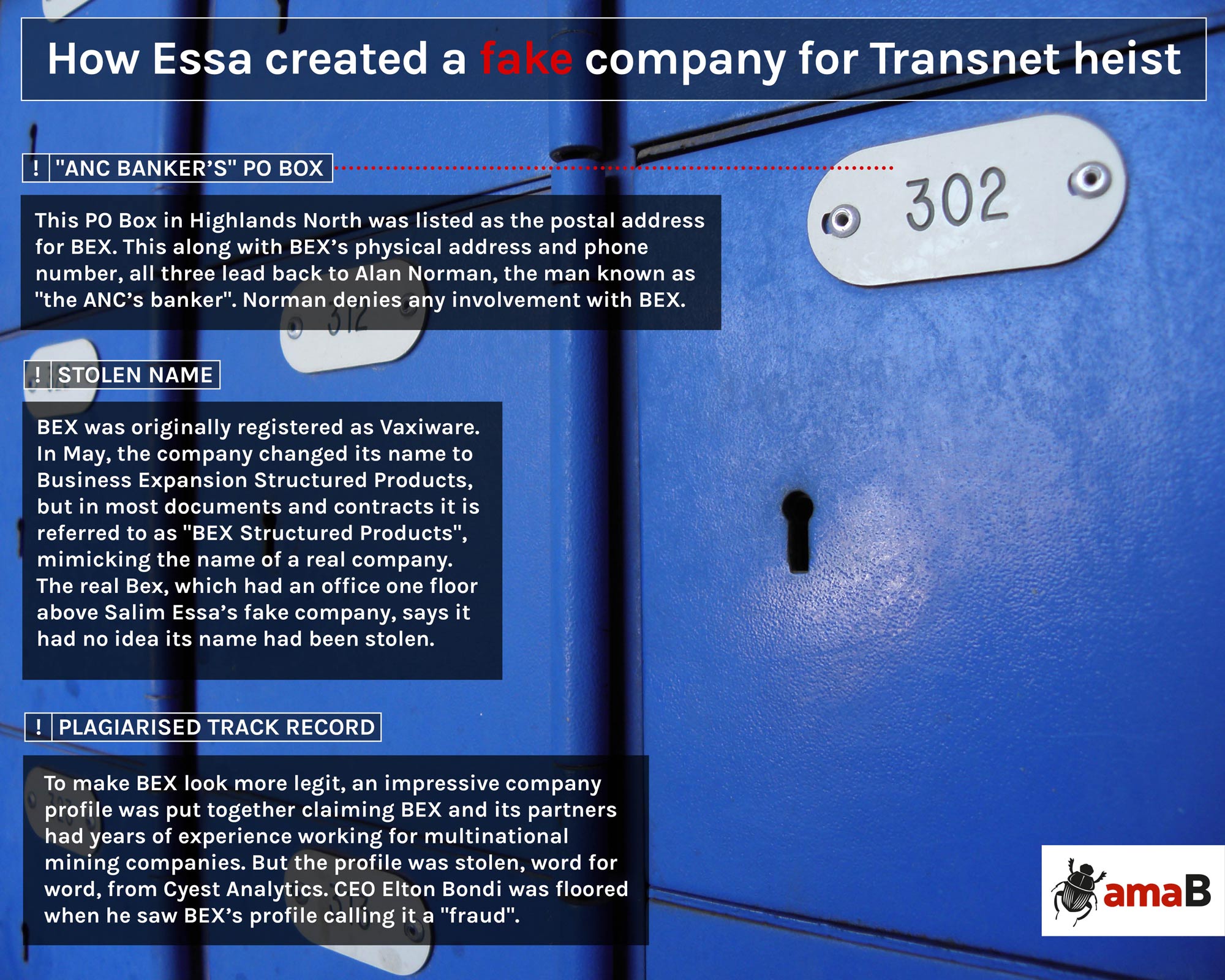

Another annexure to the Werksmans report was a “company profile” purportedly provided by Bex to CNR. Some research revealed the profile had been hijacked almost word-for-word from a real company, Cyest Analytics.

So we spoke to Cyest.

Cyest fingers ICM as the hidden hand behind Bex

Cyest knew nothing about the profile presented in the name of Bex and was understandably unhappy about their credentials being abused in this way to give Bex some bogus solidity.

Cyest chief executive Elton Bondi immediately pointed fingers at ICM and gave the following account.

“During 2015 Cyest was approached by Integrated Capital with a view to sourcing a BEE partner and forming a joint venture company… Cyest did not ultimately ever enter into any venture. “During this period, I did however gladly provide Integrated Capital with Cyest’s company profile, which they requested in order to expose us to potential partners and opportunities.”

Bondi said ICM strung them along for months and he eventually terminated the relationship.

“To the extent that Cyest’s credentials appear in any documents submitted to Transnet, CNR or Bex, it is unauthorised, without Cyest’s knowledge and a fraud.” (Gundelfinger later said his clients were unaware of how Cyest’s profile had been hijacked.)

Bondi said that, behind his back, Angel had approached a Cyest employee, Tony Savides, in connection with the Bex CNR relocation costing for Transnet.

“Savides informed me that he initially refused Angel due to his own time constraints, but then did ultimately agree to render such services … in his personal capacity.”

Without Cyest’s knowledge, ICM would use the model Savides produced to justify the massive relocation cost paid to CNR.

Bondi is still angry with the “Minyan”. He told us: “The more we uncover about what happened back in 2015, the clearer it seems that this was an act of extreme betrayal and premeditated deceit; these were not mere strangers to us, we had worked with them in the past, and we knew them all personally. They looked us in the eye, they smiled and they plotted.”

In the meantime we had prepared written questions and sent them off to ICM’s directors (Angel, Shane and Chipkin) on the morning of Friday 15 June with a request that they revert to us by midday that Monday.

We also wrote to Essa and CNR.

The deadline came and went with no response.

On Thursday 21 June we heard that Gundelfinger’s partner had been pushing to set up a meeting with Bondi. Bondi had refused.

On Friday Gundelfinger called requesting that we meet the following week Wednesday, 27 June. We agreed.

The innocent ‘little fish’

That day Gundelfinger and Natha presented us with a detailed explanation (see here) complete with annexures detailing on-payments by Bex of the money that had flowed in from CNR.

They pressed home this demonstration of good faith with a display of impassioned sympathy with their clients.

Said Natha: “The point is the smaller guys here, like our guys, are getting nailed for trying to have done business … when they were entering into transactions in a very bona fide manner… They provide services to a businessman [Essa] who they believe to be legitimate and then when all of the shit hits the fan everyone wants to now go and point fingers at the little guy…

“In their own community, people are calling them the ‘Gupta trio’ and things like that…”

Added Gundelfinger: “These guys have got families, I mean, they’ve been wiped out.”

But even on its own terms the Gundelfinger narrative tested credibility.

Some highlights…

Selwyn Nathan made the introductions

Gundelfinger told us the association with Essa began in 2014 when Selwyn Nathan introduced Essa as “a credible BEE businessman and potential client”.

It is worth flagging Nathan before he exits the stage.

He is a former golf-pro turned sports marketer who hit the big time with Vodacom’s sponsorship arm. He served on the 2010 World Cup local organising committee and has strong business and political connections, mostly golf-related.

If he only made the introductions, we asked ourselves, why was he even legally represented?

Clues to that might be found in whispers about Nathan being “the boss” behind ICM. Back in 2015 he was listed prominently on the ICM webpage as the “non-executive chair”.

Gundelfinger told us: “Nathan was never a director of ICM and owns no shares therein.”

He did not respond to a question about whether Nathan previously held shares, but Gundelfinger himself originally described Nathan as ICM’s “erstwhile chair”.

Nathan’s son Daniel also featured obliquely in the Gupta saga via his company Scarlet Sky, in which Essa associate Kuben Moodley held a 60% share when it scored a marketing contract with state-owned diamond company Alexkor.

In November 2014, when Daniel Nathan bid for the diamond marketing tender, his application noted that correspondence should flow through his “corporate advisors”, addressed to one Marc Chipkin of Integrated Capital Management.

With this in mind, let us return to the Gundelfinger narrative of how Shane, Angel, Chipkin, Shaw and Tichauer became entangled in the Bex web.

The Gundelfinger narrative

Central to Gundelfinger’s version is that ICM delivered legitimate work to make a serious assessment of the relocation costs and that no-one involved had any basis to question the bona fides of the Bex contract or the people involved.

In particular, Gundelfinger’s account suggested that Essa had consulted experts provided by ICM before the contract between Bex and CNR was signed, meaning the relocation estimate – and Bex’s commission – was based on realistic figures.

Let’s re-cap what we know about the Bex contract with CNR.

The contract was signed by Shaw on 25 April 2015.

It provided that the Bex commission would be whatever Transnet paid over-and-above R580-million. In other words, if Transnet did not agree to pay at least a “base cost” of R580-million, then Bex would get nothing.

So it would make sense that anybody negotiating this deal would have a good idea about the real costs of the relocation before signing – if it was a genuine deal, that is.

To that end Gundelfinger claimed that his clients’ involvement in the CNR project began in March 2015 when ICM met with Essa about assisting Eric Wood with a financial modelling project.

Wood, of course, is the fourth Musketeer of the “Gupta trio”, a director of Regiments Capital who would later take the consulting arm of Regiments across to ICM to begin the formation of Trillian.

Gundelfinger said Chipkin and Angel met with Wood in April 2015, together with Tony Savides and Michail Scholiadis, two employees of Cyest (the company whose profile was secretly hijacked by Bex) because they were experts in financial modelling.

Gundelfinger told us that at the meeting Wood confirmed that Essa’s client was CNR.

Gundelfinger said that Wood told the meeting that Bombardier’s cost estimate was in the region of R620-million: “Bombardier’s estimate… gave us [ICM] comfort as to the enormity of the quantum.”

Wood, however, denies providing any such information. (Wood denied the meeting concerned CNR at all, something contradicted by all the other witnesses.)

“Shortly thereafter,” Gundelfinger wrote in his narrative, “Essa followed up with ICM to confirm if ICM could deliver on the financial cost analysis model.”

Essa proposed ICM – like Bex – would be paid a “success fee” only once Transnet agreed on the relocation payment to CNR. Then ICM would get a base fee of R3-million plus an 8.5% share of Bex’s commission from CNR. (ICM would eventually earn about R6.8-million or more.)

So it stood to reason everyone needed to know what they were getting into before Bex signed the commission contract with CNR on 25 April.

In other words, according to the “innocent” narrative, Essa was contracted by CNR because it needed genuine help to work out what extra it might cost them to base themselves in Durban rather than Pretoria.

Essa then approached Wood for help. Wood approached ICM. ICM brought in the experts from Cyest who laboured to come up with a cost estimate.

On that basis everyone was confident they could justify a figure of more than R580-million to Transnet and earn their commission percentage.

There was one big problem with that narrative.

You see, we knew the briefing meeting with Wood didn’t happen until 6 May.

That was nearly two weeks after the Bex commission contract had already been signed, stipulating a R580-million threshold before any success fee (over and above ICM’s R3-million base fee) would be paid at all.

No rigor required

What Gundelfinger didn’t know was that we already had a sworn statement from Savides in which he confirmed that he was approached by Angel on 6 May 2015 to produce the costing model and that he did so overnight, delivering it the following day.

In other words, according to Savides, the model used to justify the R647-million (that Transnet ultimately agreed to pay) was drawn up with only the most cursory research – and only after the commission contract was already signed.

Savides said he agreed to help ICM “as a personal favour” because Angel said he desperately needed help with the mechanical task of putting a model together overnight.

“He [Angel] insisted that I help, emphasising that his requirement was for a 24-hour turnaround and clearly indicated that detailed rigor was not necessary in this case…

It was a case of “Go onto Google, and look up average price of forklift, that’s it,” Savides told us on a different occasion. “All of it [was] basically desktop research, done in a couple of hours. That was certainly all we did.”

His colleague Scholiadis confirmed this: “The exercise took less than a day and Tony and I completed it after hours on the first day we received information. It was heavily driven by the assumptions we received…”

Those assumptions, Savides insisted, were provided mainly by Angel.

Gundelfinger asserted extensive work was done over weeks but Savides contradicted him.

“Clive came back to me 3 more times to request minor changes… most of these changes took less than an hour,” Savides said.

In a subsequent email Savides told us, “Neither I nor Michail [Scholiadis] received – or even asked for – any payment for this work. He [Clive] did offer to pay, which I declined, based on it being a favour of a nights worth of help… He then recommended that as a gesture he would make a donation to a charity…”

Even more intriguing was an email Savides attached which he had received from Angel shortly after the meeting of 6 May.

Narayan: the Gupta man provides input

The email Savides had received came not from [email protected] as one might expect if Angel was merely Bex’s service provider.

Instead it came from “Clive” using Bex’s own email account, [email protected].

The email Angel forwarded at 3.05 pm was from one Ashok Narayan, who had written to Angel, saying: “Hi Clive, some indicative figures from CNR which you will have to add some meat to…”

Ashok Narayan was of course the Guptas’ right hand man.

So the two people thought to be most responsible for feeding the data into the model were Narayan and Angel.

Angel’s use of the Bex email address and his apparent familiarity with Narayan also suggests ICM were more deeply involved than Gundelfinger tried to make out.

Not so innocent?

The information from Savides badly undermined the Gundelfinger narrative. (Shortly after we revealed the Savides statement in questions to Gundelfinger, he corrected himself and confirmed the meeting with Wood was on 6 May 2015.)

If the meeting – and any serious work on the figures – only happened in May, how could Bex – and by extension ICM – bind themselves in April already to a fee based on pushing up an already massive R580-million relocation charge that Transnet might not agree to pay?

If the number crunching was perfunctory, rather than rigorous, then where did the confidence in that R647-million come from?

It suggests that what Essa was actually involved in was an effort to retrofit a bloated estimate that he could sell Transnet in order to come up with a high enough figure to beat CNR’s benchmark and deliver his commission.

It suggests, too, that ICM’s involvement could not have been innocent, if they signed up for a deal with a R580-million threshold before numbers had been properly crunched.

No sensible businessman would blindly agree to such a deal if the contract was really “at risk” – though, admittedly, ICM’s risk was minimal, given they had apparently invested very little in the project.

The Savides version fuels suspicion the deal was instead based on a bet that Essa’s influence peddling would deliver Transnet’s agreement, provided CNR could present Transnet with something vaguely plausible to justify the cost.

We put these contradictions to Gundelfinger.

Gundelfinger disputes our interpretation

He responded with bluster: “It appears that you are prejudiced and have clearly displayed a bias adverse to my clients, my clients will not submit themselves to a loaded interrogation…”

On the evidence, Gundelfinger countered: “Savides’ version that he did it in ‘haste’ is nonsense. This was an interactive process and a number of versions were prepared…”

Gundelfinger included two more emails which he claimed showed that “detailed research was undertaken” and that correspondence was still continuing in July.

Gundelfinger also said Angel’s use of the Bex email address “does not in any way demonstrate that Angel was one of the controlling hands behind Bex – which he emphatically denies”.

He said Essa had asked Angel to use the Bex mail-box.

Gundelfinger declined to explain what ICM directors understood Narayan’s role to be and whether they were aware of his connection to the Gupta family.

Gundelfinger confirmed that the meeting with Wood and Savides took place only on 6 May – after the commission contract with a R580-million base price was already signed off in April – but failed to deal with the problems this created for his narrative.

In fact, we learned later that CNR had circulated a draft of the commission agreement internally as early as March. It shows that at that stage the Chinese were pushing for a base price of only R280-million, which had supposedly been reached “after extensive research and negotiations”.

Clearly the base price was a moving feast.

Shane’s role: was a Transnet director batting for the other team?

Gundelfinger also provided an image of an electronic meeting calender that suggested Shane, who had also been a Transnet director since December 2014, was not part of the 6 May meeting.

It was becoming apparent that Gundelfinger was keen to distance Shane from the relocation project.

Was the “Minyan” not only abetting suspect deals but doing so when they were also conflicted because of Shane’s position at Transnet?

Wood seemed to be saying so: he gave us a copy of a request for the same meeting which was sent to him by Chipkin. This particular meeting request included Shane.

Angel and Chipkin have denied that ICM did any work for Trillian, insisting the two of them worked for Trillian through a separate company that didn’t include Shane and that they provided only limited, “startup” services.

Presumably this was a distinction they were keen to underline because Shane seemingly did not disclose to Transnet any conflict arising out of his interest in ICM, even when ICM became intimately involved with Essa’s contract to lobby Transnet on behalf of CNR.

Gundelfinger argued that because the Transnet board had approved the relocation in principle in May 2014, before Shane joined the board, there was no conflict of interest.

He ignored the fact that the real issue was the amount paid to CNR, which was only decided in July 2015 after ICM got involved – and after Shane was already at Transnet.

Gundelfinger insists Shane “never saw let alone approved any contracts or payment in relation to CNR”.

Legal Frontiers: what did the other “service providers” know?

When we first dealt with Gundelfinger he was representing Shaw, who, it will be recalled, had signed the Bex contract with CNR on behalf of Bex.

Gundelfinger explained Shaw had got involved because Essa had requested ICM to assist with the registration of Bex as a company.

ICM had a long standing relationship with Legal Frontiers, to whom it introduced clients for company secretarial and administrative functions.

ICM introduced Essa to Legal Frontiers, which procured a shelf company with a VAT registration number and a Standard Bank account.

Gundelfinger said Essa provided the name for Bex and “all relevant FICA documents such as the physical address, registered office, directorships and shareholding for Bex in writing”.

Those addresses are intriguing. The physical address, PO Box and telephone number for Bex provided in the fake company profile all lead back to one Alan Norman.

The ‘ANC’s Banker’

Norman is no stranger to politically connected deals. He is a former Absa executive described in some media reports as “the ANC’s banker”, with links to ex-ANC treasurer general Mendi Msimang and ANC business front Chancellor House.

Most recently Norman featured in an amaBhungane exposé about the ANC’s plans to spend R50-million on a secret campaign targeting opposition parties in the 2016 local government elections.

According to the report, invoices on the covert ANC project were at one point routed via a company of which Norman was the sole director.

Norman told amaBhungane he had no idea of how his contact details landed up being linked to Bex, which he said he had never heard of.

Norman said he had “never encountered” Essa and while he did know Shane, Angel and Chipkin, he had “no business dealings with them, ever”.

So we turned our attention to Shaw and Legal Frontiers, but the contradictions multiplied alarmingly.

The mysterious Mr Hasware

Gundelfinger’s version was that Essa was responsible for all the instructions to Shaw and Legal Frontiers on behalf of Bex even though, on paper, he was neither a director nor shareholder.

Gundelfinger explained that Essa requested the services of an alternate director for Bex to act on written instruction should the “main” appointed director not be available.

“Essa informed us that both he and the ‘main’ director, Tasfique [sic] Hasware travelled extensively abroad as part of advising CNR. As one of Legal Frontiers’ services they agreed to provide an alternate director to Bex. Mark Shaw, an employee of Legal Frontiers, was therefore appointed as the alternate director…

“Essa requested (via a signed board resolution) that the alternate director, Shaw, sign the Bex/CNR contract. According to Essa, Hasware was consulting overseas at the time.”

Gundelfinger said: “All instructions with regard to Bex were communicated in writing by Essa and/or his agent Taufique Hasware. We [Shaw and Tichauer] did not meet Hasware, but this is not uncommon since there are many clients with whom we don’t meet in person but receive instructions and FICA documents in writing.”

Gundelfinger said in around September 2015, Essa told ICM that CNR had been successful with Transnet and they would be making payment in terms of the commission agreement.

It should be noted that by the end of July, 2015 amaBhungane had published a front page story in the Mail & Guardian concerning how telecoms firm Neotel paid tens of millions of rands in “commissions” to another letterbox company to clinch deals worth R2-billion from Transnet.

The article highlighted the central role of “Gupta man” Ashok Narayan and flagged the mysterious Taufique Hasware, whose most recent employment appeared to be as a small-time Johannesburg carpetseller, not a jetsetting dealmaker.

Perhaps no-one at ICM or at Legal Frontiers read the story.

More “service providers”

Bex’s money was channelled on to four other nondescript companies, Gundelfinger revealed.

Explaining Shaw’s role and the on-payments made by Bex, Gundelfinger told us: “As Essa had still not completed the bank account forms he was not the signatory on the account. Therefore, he instructed Legal Frontiers (who were still signatories) to facilitate the payments due to the various other service providers whom Essa advised had completed work for Bex on the CNR project.”

Gundelfinger said that Essa “delivered four invoices to Legal Frontiers’ offices on behalf of other services providers whom he said had worked on the CNR initiative to be paid by Bex and gave instructions to make payment”.

Gundelfinger helpfully provided four invoices showing that, of the commission received by Bex (R76-million including VAT), R66-million had been paid out within a short time to four other letterbox companies.

This was something that should have raised red flags for Shaw – and it implicated him further if he was involved in making the payments – as Gundelfinger was suggesting.

In fact, it looked so bad for Shaw that, the day after we received the narrative explanation, we contacted him directly to confirm that he was indeed represented by Gundelfinger and attaching the answers provided in his name.

Shaw did not reply, but the next day, 29 June, we received a missive from Gundelfinger to which was appended a signed confirmation from Shaw that Gundelfinger was his lawyer and stating: “I confirm the contents of the narrative and reply to questions insofar as it relates to myself.”

That did not last for long.

Accumulating lawyers

We had discovered that Legal Frontiers was 51% owned by a Mr Sudesh Rocharam.

We thought we had better get his version, so on Monday, 2 July, we sent him Gundelfinger’s narrative for his comment.

The next day, Tuesday, we received a reply from his lawyer – Brian Kahn – which made it clear that this was the first Rocharam had heard about the whole story, including our inquiries.

Apparently, neither Tichauer (who held the other 49% of Legal Frontiers) nor Shaw had bothered to inform him about the ruckus developing around his company.

Kahn told us: “Our client has no personal knowledge whatsoever of the (possible? implied?) unlawful and/or improper activities to which there is reference in the documentation enclosed to your email…”

Kahn also denied that Shaw was ever an employee Legal Frontiers.

By later on that Tuesday we received a letter from Russell Kantor of the venerable firm of Tugendhaft Wapnick Banchetti & Partners, indicating they were now the legal representatives of Shaw and Tichauer and were taking instructions from their new clients.

We were accumulating lawyers at a frightening rate.

Accumulating versions

There was a final dizzying round of different versions, mostly enveloped in clouds of legal jargon (Kantor is particularly fond of calling a question an “interrogatory”).

Kahn, whose style is brusque, gave Shaw short shrift saying, “Mr Shaw occupies premises within the building that Legal Frontiers carries on business and from time-to-time (and purely on an ad hoc basis) his view or opinion may be sought on something or other.”

Gundelfinger, no longer representing Shaw and Tichauer, underlined his view of the innocence of ICM’s involvement, noting: “At no time did my clients believe or suspect that funds coming from CNR (a reputable Chinese multinational company) were not as a result of a legitimate contract and services provided by Bex to CNR’s satisfaction.”

Kantor had the toughest job, given that Shaw had foolishly signed his name not only to a dodgy commission contract, but also to Gundelfinger’s version of events, which did not place him in a happy light.

Kantor’s version: Did Shaw lie to us? No ways!

Kantor did his best to plaster over the contradictions, maintaining, in his inimitable style, that there were none.

“Save to the extent otherwise indicated, the statements made by Mr Shaw and those advanced on his behalf do not talk across one another. Moreover you are incorrect in suggesting that the documents referred to are disjunctive.”

His concession appeared to extend only to confirming that Shaw was not an employee of Legal Frontiers, as set out in the Gundelfinger narrative, with which his client had previously concurred, in writing.

Kantor ascribed this to a mere oversight: “Insofar as the signed declaration is concerned, it was submitted to you by Mr Gundelfinger prior to either of our clients having had sight of that document. Upon a more careful reading of the statement, Mr Shaw observed that it contained factual inaccuracies, as and by way of example, the averment that he is an employee of Legal Frontiers… In the circumstances, there are no ‘contradictory statements’…”

Kantor maintained steadfastly that Shaw had no reason to doubt the probity of what he was doing.

“There was nothing on the face of the [commission] agreement to suggest that the transactions therein contemplated were sinister or uncommercial and nothing signalling that the agreement was tainted by any irregularity or unlawfulness.”

Kantor admitted thatShaw never met, or spoke with Hasware and claimed – in contradiction with Gundelfinger’s version – that neither Shaw nor Tichauer had any communications with Essa whatsoever.

It seems that, on his version, Shaw, a registered auditor, entered into a R580-million contract on the strength of a piece of paper which appears to have spelled Hasware’s first name incorrectly.

Hasware’s directorship of Bex was only officially lodged on 27 March 2017 (nearly two years after the CNR transaction) but Kantor insisted this did not legally preclude Shaw from recognising Hasware as a de facto director.

Kantor said Legal Frontiers’ client, from whom instructions were received concerning the formation of Bex, was neither Essa nor Hasware, but he declined to identify who it was.

Somewhat astonishingly, considering the wording of the Gundelfinger narrative, Kantor denied that Shaw, Tichauer, Legal Frontiers or Tichauer & Bloch had anything to do with the R66-million on-payment to the four letterbox companies.

“You must not… confuse, as you seemingly do, the signatory on the accounts (on the one hand), with persons transacting on the accounts (on the other hand). Accordingly, your assumption that Mr Shaw, as signatory on the accounts ‘was therefore the only person able to execute these payments’, is demonstrably incorrect.”

Kantor declined to reveal who made the payments.

“Neither Mr Shaw, Mr Tichauer, Legal Frontiers nor Tichauer & Bloch were participant in or had any reason to believe that there was any unlawful scheme. There was no mischief on their part and any suggestion to the contrary would be scurrilous, devoid of any truth and highly defamatory of these persons.”

So there.

While we were wrestling with assorted members of the legal fraternity in Johannesburg, we were also sounding out the community reaction.

Back to the Minyan

The “Gupta Minyan” has made quite a lot of people upset it appears – and many believe it is time to pass judgement.

There seems to be a consistent view of Shane who is regarded as flashy and arrogant – while Angel, in the words of one former co-worker, “wants to be like Shane when he grows up”.

Opinion is more divided on Chipkin, who is “considerate – a much nicer guy”, according to the same co-worker.

It was during this time that we learned that Shane and Angel are facing another problem, namely an unrelated criminal case.

Gundelfinger and Natha appeared crestfallen when we revealed that we knew Angel and Shane were accused 3 & 4 in case 43/2018 at the specialised commercial crime court in Johannesburg.

The case involves a company called Biggest SA Trading (BSA) which focused on the distribution and delivery of liquor to various wholesalers nationwide.

In November 2014 BSA was sold for about R30-million to Super Group, the listed logistics giant founded by Larry Lipschitz.

Now BSA, its auditor and its directors, which included Angel and Shane, have been charged with fraud, based on allegedly misrepresenting the value of the company which, according to the charge sheet, actually had a negative value of R26.7 million.

Both Shane and Angel have indicated that they viewed themselves as victims and not suspects in the matter, but neither the prosecutor nor Super Group seem convinced. The trial has not yet got underway.

All in all the “Gupta Minyan” is regarded as “bringing down the Jewish name”, as one observer put it.

In a community that exists as a tiny minority in South Africa and often sees itself as under siege, this is seen as an offence that adds to Jewish vulnerability.

As Krost-Maunder put it in her SAJR editorial: “When other people are involved, we can be angry and frustrated, but it is embarrassing and humiliating when our own are involved…

“Is it okay for them to be sitting on boards? And how do you feel when they walk down the aisle at your shul on Shabbos? Do we have a right to look down our noses at them? They have not had their day in court.”

Despite the seeming implausibility of their versions, it appears unlikely they will ever face that day, given the weakness of the state and the dedication of their lawyers.

On the other hand, social rejection as a punishment is as old as human society and is still used by many customary legal systems.

If the “Gupta Minyan” find themselves snubbed on a Friday night, there may be a certain justice in that.

*Additional reporting by Susan Comrie