As a whole, Africa had the warmest August since at least 1910, with temperatures 1.4°C hotter than the long-term average.

It was a sunny afternoon in May when Lulama Shongwe made her way to the University of Pretoria clinic. It had become second nature for her to quickly pop into the campus health facility in between classes to receive her usual birth control shot, Nur-Isterate. She did this once every two months.

But this time, things were different.

When Shongwe, 24, arrived at the clinic, the nurse told her she would either need to switch to a contraceptive implant or pay for her injection at a private doctor or pharmacy.

The clinic had run out of stock of Nur-Isterate. The contraceptive implant the nurse offered was the only birth control method other than condoms that the clinic had in stock.

The bi-monthly injection would cost Shongwe about R70 at a private pharmacy. “I use the campus clinic because it’s close to me and free,” she explains. “I felt like it wasn’t right that I would have to start paying for my contraceptive.”

Shongwe sips her cup of coffee.

“If I cannot get Nur-Isterate on campus, it means that I must find the extra money to get it privately,” Shongwe says. “I work part-time, but even then every single cent of my income is accounted for already.

“Where is that money going to come from every two months?”

Watch: We put SA’s new condoms to the test

Health workers in North West and Mpumalanga say they’ve had to turn patients away because of a lack of oral contraceptives.

“We’ve been encouraging women to change their contraceptive but some are reluctant. They are saying they are used to the pill they’re on, or they complain about side effects from other drugs,” says a Mpumalanga health worker who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

Five Gauteng universities have confirmed to Bhekisisa that they have been forced to ration contraceptives since they began experiencing shortages in January: The universities of Johannesburg, Pretoria and the Witwatersrand; Tshwane University of Technology and North West University’s Vaal campus.

The rate of unplanned pregnancies in South Africa is high. A 2017 South African Medical Journal study found 64% of almost 330 women in KwaZulu-Natal hadn’t planned their pregnancies. About three-quarters of the study’s participants were between the ages of 18 and 30 years.

The provision of contraception to young women at universities and colleges is one of the goals under the country’s latest HIV plan. Provincial health departments supply birth control to public tertiary institutions, as long as the universities submit monthly statistics about use to the department.

The shortage has left these institutions scrambling.

“We’ve had to share resources across our campuses as some have more patients than others,” says University of Johannesburg communications officer Luyanda Ndaba.

“Unfortunately, communication regarding shortages was only conveyed upon enquiring about the short supply of contraceptives.”

According to the national health department, there are country-wide shortages of oral and injectable contraception, including the birth control pills Oralcon, Trigestrel and Famynor. Although the scarcity of the shot Nur-Isterate may be because of tender delays, the shortage of popular pills is being blamed on international pharmaceutical company Mylan’s inability to meet demand.

There are concerns that the drug manufacturer may have deliberately undercut local suppliers to secure state tenders only to fail to deliver.

Nur-Isterate producer Bayer is government’s sole supplier of the two-month injection. The previous tender for the drug ended in September, but the new tender was only awarded five months later in February, says Bayer Southern Africa’s head of communication Tasniem Patel.

National Treasury attributed the delay to prolonged price negotiations. Patel says that once prices were agreed upon, the company was given three months to start supplying South Africa with the shot.

She explains: “Bayer was only compelled to start supply between the end of May and early June. Bayer has already delivered some stock to all nine provinces so far.”

Patel says Bayer is working to fill a backlog because of the late awarding of the tender.

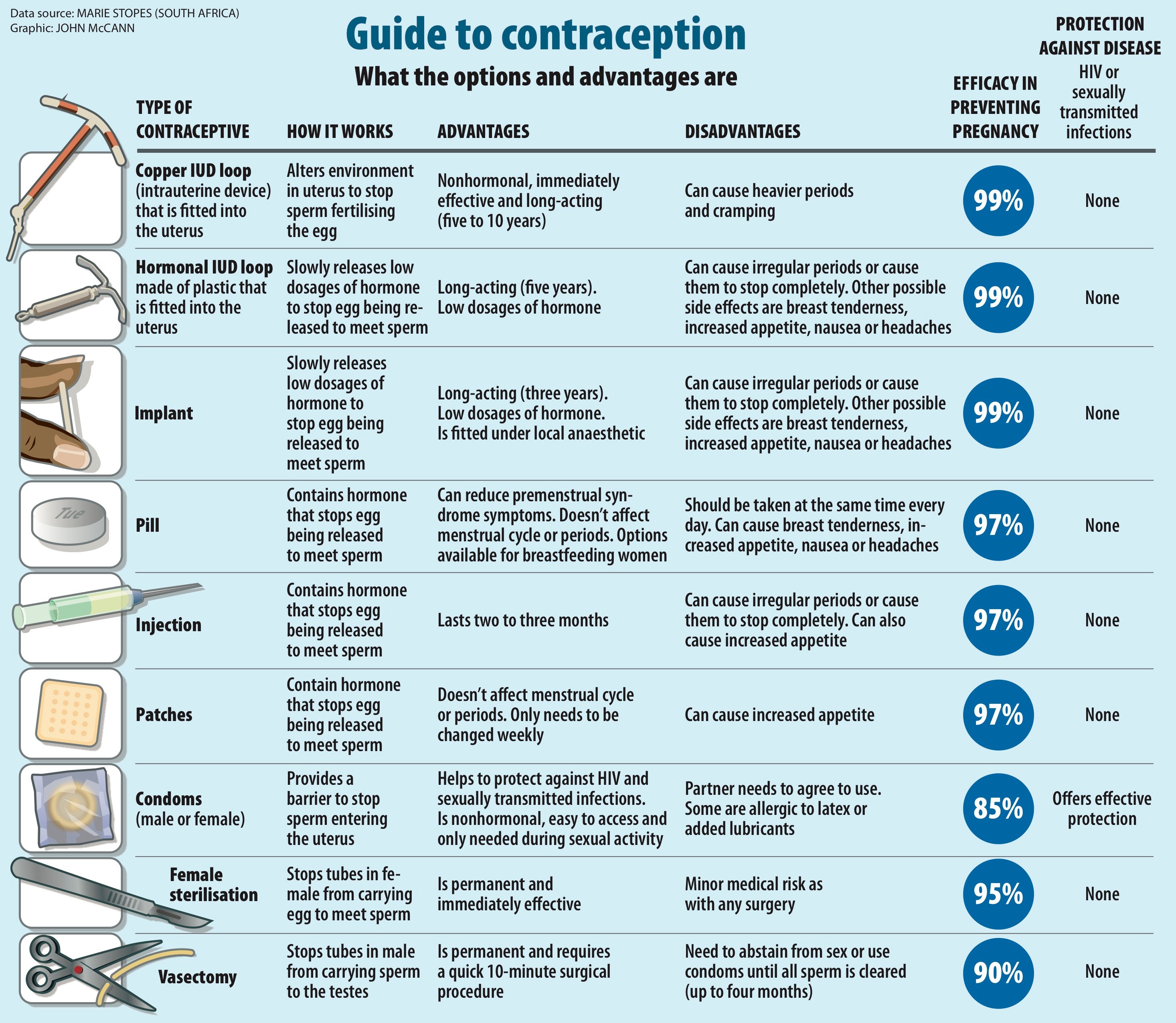

Which contraception could be right for you? Take a look and find out.

After it won 87% of the health department’s latest three-year tender, Mylan started to supply the public sector with the bulk of its oral contraceptives. To help safeguard medicine supplies, tenders are often split between several companies. So, although Mylan is the sole tendered supplier of three oral contraceptives (Oralcon, Famynor and HY-AN), it was awarded a joint tender with local pharmaceutical company Aspen Pharmacare to provide a birth control pill that combines two drugs, levonorgestrel and ethinylestradiol.

Mylan sells this drug under the brand name Trigestrel and was awarded the majority share (70%) of the state contract for the pill. But Aspen markets the same tablet under the name Triphasil.

The international firm was able to offer the pill to government for half the cost — at R2.70 for a month’s course — than Aspen could provide it at.

The significant difference in pricing has raised concerns within the pharmaceutical sector that Mylan strategically lowered its prices as a way to drive Aspen out of the market in what is known as “predatory pricing”.

As part of predatory pricing, pharmaceutical companies deliberately set the price of medicines very low — at times even lower than the cost of manufacturing — to secure market share or create barriers to entry into the market for potential new competitors, explains Leena Menghaney, the head of the international humanitarian organisation Doctors Without Borders (MSF) Access Campaign for affordable medicine in India.

“Theoretically, if competitors or potential competitors cannot sustain equal or lower prices without losing money, they go out of the market or supply chain. With no or fewer competitors, drug makers can then push up medicine prices,” Menghaney explains.

Predatory pricing is considered anti-competitive and is illegal in South Africa.

“I cannot say whether or not there has been predatory pricing. The importer’s [Mylan] bid price equates to about eight cents per tablet,” says Aspen senior executive Stavros Nicolaou.

“There are not many things that can be sustainably produced at eight cents per day or approximately R2.20 per month. At this price, it becomes difficult to price a product sustainably and ensure patients receive medication on a consistent and sustainable basis.”

Aspen’s average price offered to the state equates to about R5.61 per patient per month, which Nicolaou believes is fair.

Mylan did not respond to Bhekisisa’s questions regarding shortages or allegations of predatory pricing. But the pharmaceutical company did confirm it is working with the health department “to provide affordable and high-quality contraceptive medications” to patients.

“We have been a reliable supplier of contraceptive medications to the people in the region,” Ritika Verma, Mylan’s head of communications for India and emerging markets, says.

“Mylan remains committed to bringing innovative contraceptive treatment regimens to South Africa. Our collaboration with the department has made it possible to increase access to existing and innovative medications in the country.”

Department of Health Deputy Director-General Anban Pillay says allegations of predatory pricing are serious and can attract penalties from the Competition Commission but are often difficult to prove.

“It is not easy to provide conclusive evidence hence we cannot make such an allegation,” he says.

He explains that as part of tendering, companies must provide a breakdown of prices to guard against exchange rate fluctuations but that this also allows the department to interrogate the accuracy of medicine prices.

Pillay cautioned that stock-outs may be because of poor planning by Mylan and says both Mylan and Aspen have had trouble supplying other drugs in the past.

Drug makers Aspen and Mylan have been in stiff competition in the past to provide South Africa — home to the world’s biggest HIV treatment programme — with antiretrovirals. (Siphiwe Sibeko, Reuters)

Predatory pricing is not new in South Africa. In 2015, there were national stockouts of the two-in-one antiretroviral drug Aluvia, for which drug maker AbbVie was the sole provider. The company’s patent prohibited generic manufacturers from supplying the medicine.

“AbbVie’s actions were a form of predatory pricing to ensure that it remained the sole supplier by lowering prices so that the South African government did not issue a compulsory license to procure generics. AbbVie could not supply the drug in time and there were no alternative suppliers, which led to a shortage,” Menghaney explains.

Compulsory licensing allows a government to make or import generic versions of medicines, for public health reasons, that are still under patent. Until recently, this kind of licensing been virtually impossible under South African patent laws.

AbbVie public affairs director

in Africa David Freundel has denied allegations of predatory pricing, saying that in 2015 the firm entered into an agreement with the Medicines Patent Pool, an international body that allows drug makers to voluntarily share patents with generic manufacturers in order to increase access to affordable medicines in developing countries.

Under the arrangement, firms in South Africa and across the continent could produce generic versions of Aluvia.

However AbbVie only signed this agreement in December 2015, several months after national Aluvia stock-outs were reported.

Many women such as Lulama Shongwe aren’t able to afford to pay-out-pocket for contraception and not all medical aids cover it.

To deal with the current shortage, Mylan and the national health department successfully applied

to South Africa’s medicine regulator the South African Health Product Regulatory Authority (Sahpra) for special permission to import a version of contraceptive pill Famynor.

Although the drug is already registered in South Africa, Sahpra allowed Mylan to bring in batches of the medicine sourced from a different German supplier with a pending Sahpra application.

Mylan and the national health department said in their application that the alternative local supplier of the birth control pill Famynor would have been Aspen Pharmacare, but the company was unable to meet demand on short notice, says Sahpra deputy director of Section 21 authorisation Shyamli Munbodh.

“That is far from the truth,” Nicolaou says. “We currently have about 200 000 packets of the birth control pill Nordette that we manufactured in case the department needed them.”

The local firm was placed on standby by the national health department as a back-up supplier, to date Aspen has not received an order from the department of health.

No one size fits all: Some women will be hesitant to switch birth control options in light of current shortages after bad experiences such as side-effects with other methods in the past.

Back in Pretoria, Lulama Shongwe is at a loss on how to find the nearest public clinic to the university.

“Even if I figure it all out, I would still need to factor in taxi fare as well as the time it would take me to get there in between classes,” she says.

Shongwe says she’s put some of the university clinic’s alternative forms of contraception to the test — but without success.

“I’ve tried the pill. I’ve tried the Implanon [under-the-skin implant]. I’ve tried [the injection] Depo-Provera — Nur-Isterate is the only that works properly for me.”

Other students are starting to worry too, Shongwe says.

“It’s just not right,” she laments. “We cannot be forced to use contraceptive methods that we don’t like.”

— Additional reporting by Laura Lopez Gonzalez