The Dieselgate scandal was unearthed in late 2015 when German automaker Volkswagen was found to have intentionally programmed its diesel engines to show lower-than-actual emission of pollutants. (Reuters)

As emission regulations become stronger for new vehicles in industrialised countries, cars as old as 25 years no longer able to meet emission standards are being exported to Africa. Air quality is suffering as a result.

Any child playing at the Uhuru garden — a recreation park in the middle of the Kenyan capital Nairobi — is oblivious to the health dangers in the air around him or her. But that air is laden with toxic pollutants, which have become a leading cause of respiratory disease in Kenyan cities.

According to the World Health Organisation, 15 000 children under five died each day in 2016 due to respiratory disease.

But the vehicles that contribute a large part of that pollution trace a long path to Africa.

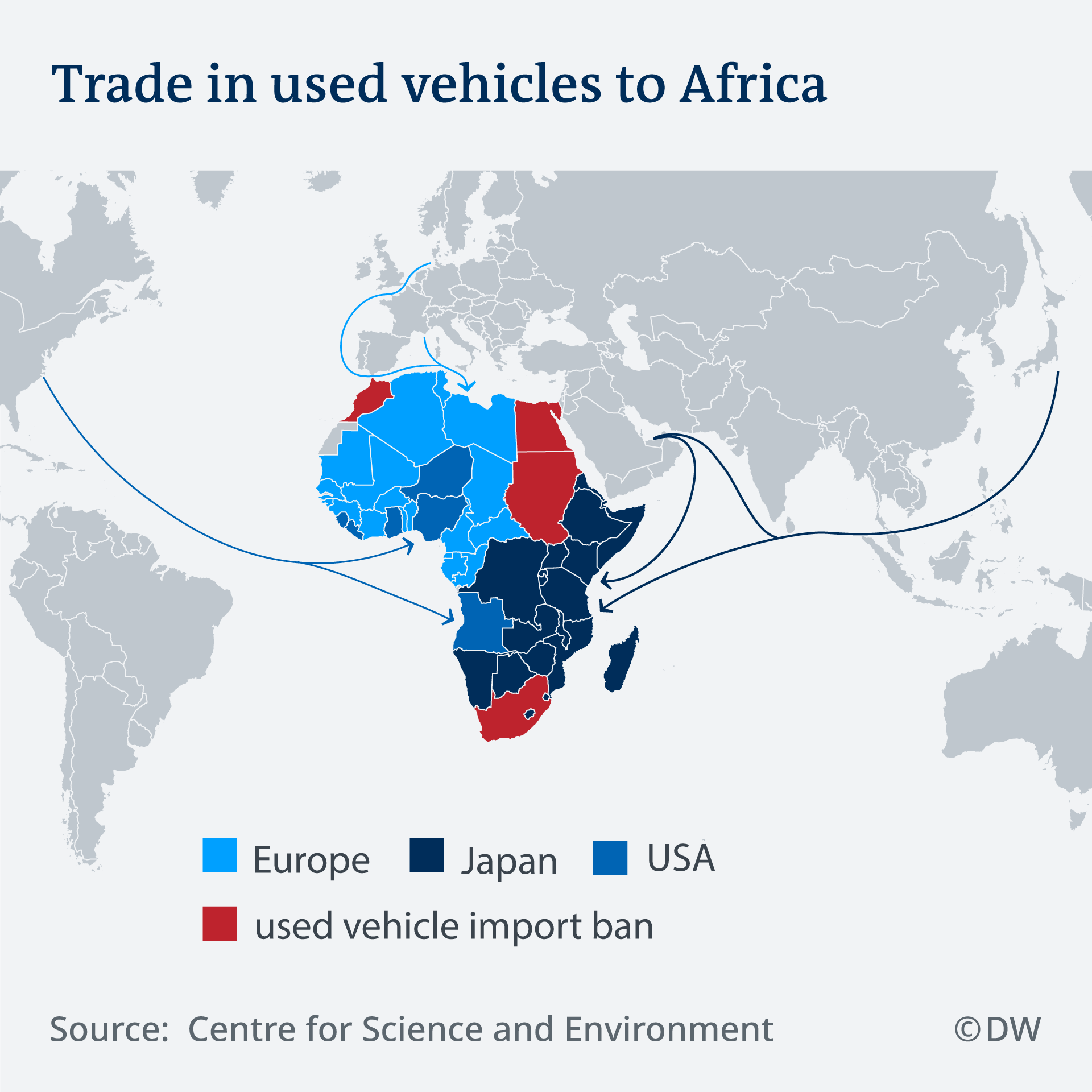

As emission regulations become stricter in the European Union, Japan, and the United States, cars no longer able to meet current standards are exported to other regions, including Africa.

In Africa, 25 countries have placed a maximum age limit on used car imports. But due to weak enforcement, cars as old as 25 years are sold in Africa.

A recent report from New Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment indicates that Germany and China account for 14% of car imports to Africa, while Japan and the US account for 15%.

As the population in African cities grows, unreliable public transport systems mean demand for cars is increasing. But low purchasing power, lack of stringent emission controls, and poor fuel quality have contributed to an influx of used cars that have been pushed out of industrialised countries by more stringent emission rules.

Dieselgate goes global

The Dieselgate scandal was unearthed in late 2015 when German automaker Volkswagen was found to have intentionally programmed its diesel engines to show lower-than-actual emission of pollutants.

Installed software allowed Volkswagen cars to meet the emission standards during laboratory testing. However, on the road, the same cars emitted up to 40 times more nitrogen dioxide and nitrogen oxides (NOx), a major air pollutant.

In the wake of the Dieselgate scandal, the European Union introduced stringent measures to ensure cars comply with the EU emission standards.

“Before being released to the market, new car models are now tested on-road in addition to the standard laboratory emission testing,” Peter Mock, EU regional lead at the International Council on Clean Transportation, told DW.

On-road inspections check nitrogen oxide, particulate matter, and carbon monoxide levels, while hydrocarbon emission levels are tested in the laboratory, Mock explained.

About 11 million Volkswagen cars were distributed globally between 2009 and 2015.

Backlash around Dieselgate has caused the value of older diesel cars in Europe to plummet. Trade — both legal and illegal — is now bringing those dirty diesels to Eastern Europe and beyond.

What goes in our air?

Vehicle emissions include toxic chemicals, heat-trapping greenhouse gases and fine particulate matter, which impact public health and heighten climate change risks.

Vehicle engine combustion and fuel evaporation processes release dangerous gases such as carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, ground-level ozone (also known as smog) and NOx. Cars and trucks also emit lead and other toxic pollutants such as benzene and formaldehyde.

World Health Organisation figures show that globally, around 7 million people die annually from exposure to polluted air.

Gerphas Opondo, executive director of the Nairobi-based Environmental Compliance Institute, warns that the transport sector is becoming a major source of air pollution in African cities.

“Cities in Africa have high particulate matter, hydrogen oxide, hydrocarbon, and carbon monoxide concentrations, recorded along busy roads and intersections,” he explained.

Apart from deaths due to air pollution, many more are sickened.

Research indicates that of the 4.2 million annual global chronic respiratory diseases, nearly 3.3 million occur in low- or middle-income countries. This includes cardiovascular and respiratory disease such as stroke and asthma, as well as increased risk of cancer.

Lack of standards and dirty fuel

Jane Akumu, air quality and mobility program officer at UNEP, told DW that a major problem is how vehicle emissions standards, tough emission inspection systems, and clean automotive fuels are lacking in the majority of African countries.

“Most African countries are yet to adopt the euro 4 standards, which were required in Europe in 2006,” she explained.

“High sulfur levels in diesel are also deterring the efficiency of emission technologies in Africa,” Akumu continued.

Low-quality, harmful fuels categorised as illegal waste are exported to Africa. In addition a lack of refineries, cleaner diesel is considered too expensive by some governments.

The majority of African countries use fuel with sulfur levels of 2 500 to 10 000 ppm (parts per million).

Combustion of highly sulfurous fuels results in emissions of sulfur dioxide, a major air pollutant.

Akumu stressed the need to utilise cleaner fuel to effectively implement cleaner vehicle technology. “Even if Africa imports a high-quality car, the maximum environmental benefits are not realised due to low-quality fuel,” she pointed out.

To curb emissions, UNEP is helping Africa implement the euro 4 standards that require 50 ppm of sulfur in diesel cars, which is the euro 4 standard. “Europe and Japan are at 10 ppm,” she noted.

There is progress, as 11 African countries, six of them in East Africa, have adopted sulfur fuel standards of 50 ppm.

Beyond that, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) is working with UNEP to harmonize emission and fuel standards in West Africa.

But standards will have to be accompanied by rigorous enforcement in order to have a positive impact on the looming air pollution crisis facing many African cities.