A Federation of South African Women

The Women’s March of 1956 is often framed as a singular moment of women’s resistance and participation in the politics of apartheid South Africa. Very little about what happened before and after the march exists in the public discourse and, as such, the years of activism and involvement in attempting to change apartheid are under-reported and poorly archived.

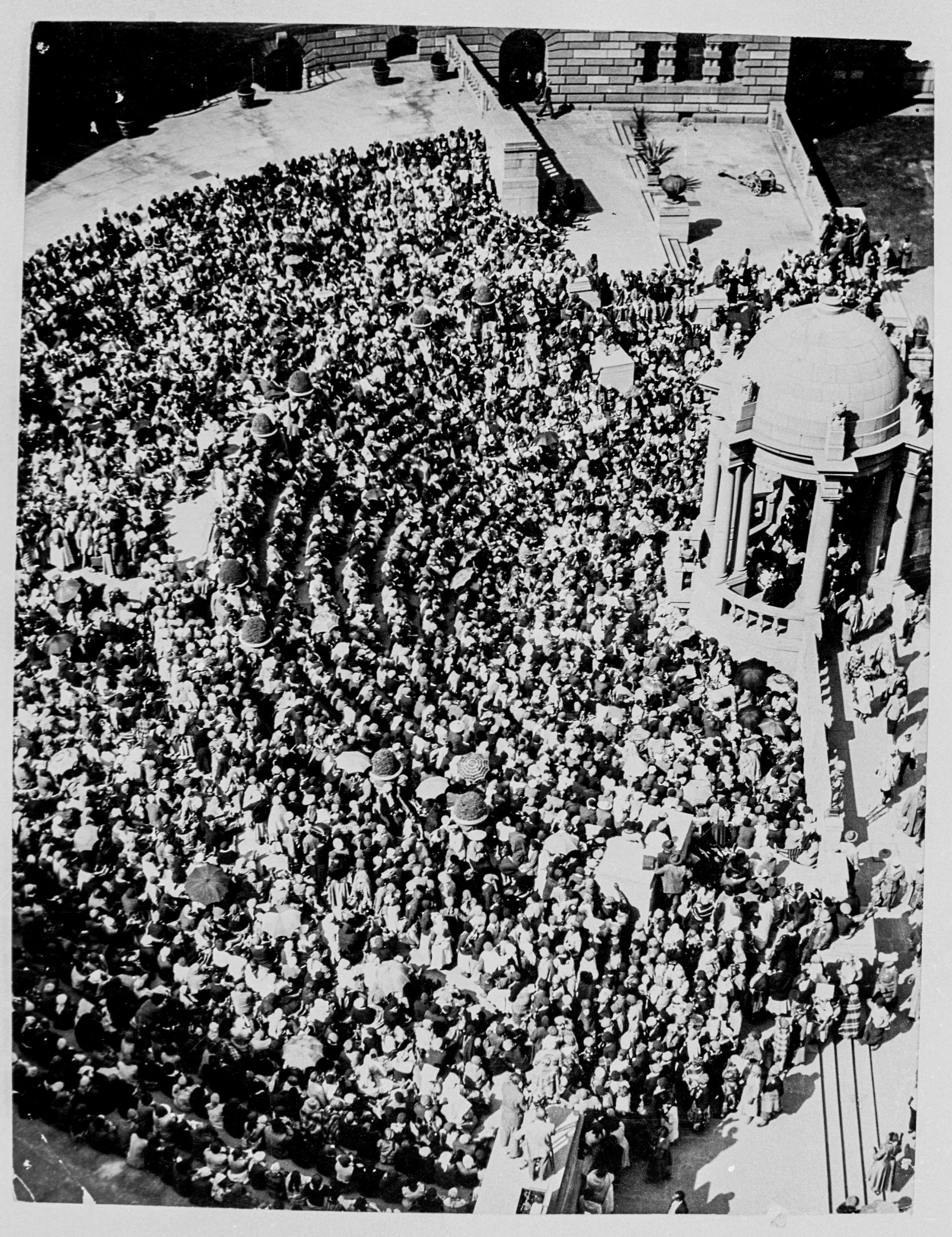

[Leading role: Fedsaw members were prominent in the Women’s March to the Union Buildings (Robben Island Mayibuye Archive)]

Even documentation about the women’s involvement in the “big” movements, such as the armed struggle, the youth movement and the pass law demonstrations in Sharpeville and Nyanga, is in short supply.

We seldom hear about the women who were at the coalface of making South Africa ungovernable in the 1980s — women who waged war in their homes by insisting that they would work and live in urban areas, raising their children in the tiny confined spaces in the backrooms of suburbia.

The consequence of this poor recollection is that hundreds of years of women’s activism and work are draped in silence. Not only are young people deprived of their history, we also do not realise that many of the gains of democratic South Africa are because of these women whom we fail to acknowledge.

In this silent history, the Federation of South African Women (Fedsaw)is rarely mentioned. The organisation was founded in 1954 and would have an immense effect two years later

on the historic Women’s March when 20 000 women marched to the Union Buildings on an August morning. Fedsaw would have an equally significant effect on the Freedom Charter, adopted in Kliptown, Soweto, in 1956.

Both the Women’s March and the contents of the Freedom Charter were influenced by the Women’s Charter adopted at Fedsaw’s inaugural conference.

It was conceived as a broad-based movement to represent as many women as possible from as much of South Africa as possible. Led by a steering committee, which was helmed by Ray Simon, Lilian Ngoyi, Helen Joseph and Amina Cachalia, the 1954 conference was attended by 150 delegates, representing about 200 000 women.

The congress also managed to get the support and delegates from African, Indian, coloured and white political organisations and trade unions. After its formation,the federation pledged support for the South African Congress Alliance, which consisted of the ANC and its allies, the South African Indian Congress, the South African Congress of Democrats and the Coloured People’s Congress, which would later adopt the Freedom Charter with input from the federation.

Prioritising women

Although it seems a given that a political organisation would be broad-based, the National Party was gutting human rights along racial and tribal lines and the creation and meeting of Fedsaw was one of the first real attempts at a broad, women-led movement.

The federation, although it pledged its support to end apartheid, deliberately highlighted the particular problems that women faced. In its charter, it stated: “We, the women of South Africa, wives and mothers, working women and housewives, African, Indians, European and coloured, hereby declare our aim of striving for the removal of all laws, regulations, conventions and customs that discriminate against us as women, and that deprive us in any way of our inherent right to the advantages, responsibilities and opportunities that society offers to any one section of the population.”

This mattered especially for black women, who, according to the racist and sexist ordering of the time, were relegated to the lowest rungs of society. The charter was clear that women’s experiences of race, class, gender, poverty and violence were directly linked to this order, noting that the evils of apartheid had affected women, especially poor black women, because the “society in which we live is divided into poor and rich, into non-European and European. They exist because there are privileges for the few, discrimination and harsh treatment for the many.”

Fedsaw did what many movements of the time were failing to do — to connect the material conditions and struggles of women with the broader struggle for freedom, not as an afterthought but as part of the struggle.

Its charter was also clear, in a way that continues to provide a measure of South Africa’s progression, about what the marginalisation of women meant for South Africa. The document served as an indictment of society, stating boldly: “The level of civilisation which any society has reached can be measured by the degree of freedom that its members enjoy. The status of women is a test of civilisation. Measured by that standard, South Africa must be considered low in the scale of civilised nations.”

Social subjugation

Through its charter, Fedsaw was also able to articulate that, although it would struggle for a free society, it would do so with women in mind so that they would not be sidelined.

One of the aspects of society it tackled was tradition, which often aggravated women’s oppression in apartheid South Africa. It was of great significance that the federation’s charter was clear about how tradition and culture could be, and often were, extensions of state violence. In a provision that remains as relevant today as it was then, the charter tackled women’s access to land and property.

It stated: “We resolve to struggle for the removal of laws and customs that deny African women the right to own, inherit or alienate property. We resolve to work for a change in the laws of marriage such as are found amongst our African, Malay and Indian people, which have the effect of placing wives in the position of legal subjection to husbands, and giving husbands the power to dispose of wives’ property and earnings, and dictate to them in all matters affecting them and their children.

“We recognise that the women are treated as minors by these marriage and property laws because of ancient and revered traditions and customs, which had their origin in the antiquity of the people and no doubt served purposes of great value in bygone times.”

The history of organisations such as Fedsaw counters the idea that it is only younger women who have pushed the view that the freedom of women is inextricably linked with the freedom of all in a society.

It also challenges the idea that African women have no history of feminism when in fact the history of African women, especially of black women, is about the struggle for liberation.

Although the federation was imperfect, it was radical in that it imagined not only a free and just society but one that was free and just for women,which, in the 1950s, was regarded as unreasonable by the status quo in the Union Buildings and in homes everywhere.