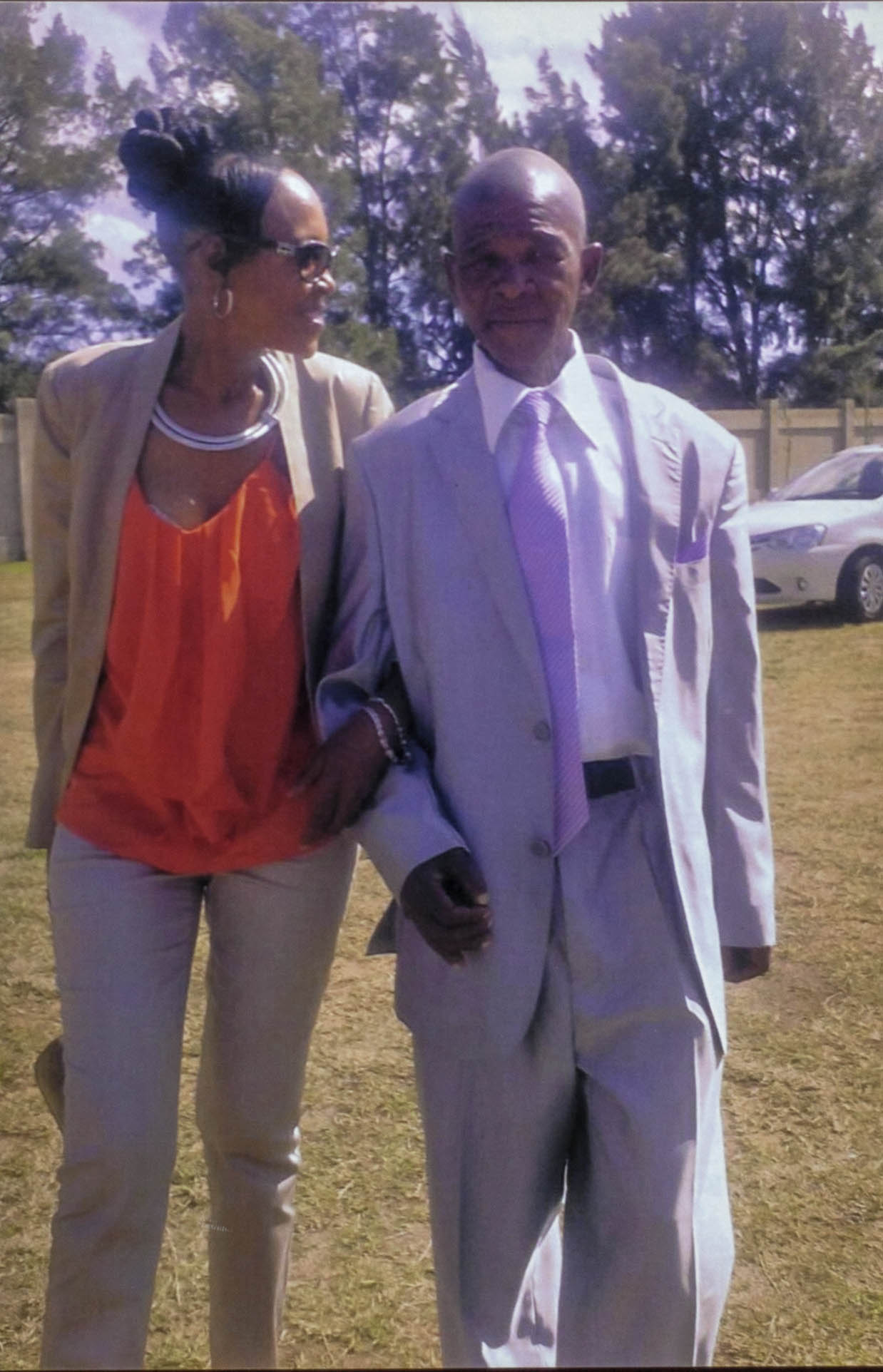

'I can't look my family members in the eye because I am the one who sent Joseph to Life Esidmeni. I thought he was safe. I will never forgive Qedani Mahlangu', says Ntombifuthi Dhladhla. (Oupa Nkosi)

It’s been almost three years since former Gauteng health MEC Qedani Mahlangu announced her intention to remove about 1 700 psychiatric patients from state-funded private hospital care.

At least 144 are dead.

More patient families are coming forward to claim against the state — the province could pay more than a billion rand in damages, The Star reports.

But no one has been criminally prosecuted for their involvement.

Last week, a committee of patient families released a statement welcoming the Constitutional Court’s removal of National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) head Shaun Abrahams. Family representatives said they hoped a change in leadership at the body would expedite the prosecution of 45 cases linked to the tragedy that have languished with the NPA since March.

The NPA remains undecided about whether it will prosecute these cases, spokesperson Phindi Mjonondwane says.

Meanwhile, Mahlangu continues to sit on the ANC’s highest provincial body — an honour she shares with chief whip and former Gauteng health MEC Brian Hlongwa.

Hlongwa was implicated in R1.2-billion in corruption during his tenure at the Gauteng health department, which the HIV lobby Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) says is responsible for the poor state of provincial healthcare.

“A culture of corruption was developed. The consequences of this are the death and suffering of poor people,” said the TAC in a recent memorandum.

The TAC and the nonprofit organisation Corruption Watch continue to call for the pair’s removal from party structures. Appearing on radio station Power FM in October 2017, Hlongwa said he was one of Mahlangu’s advisors after the tragedy:

“I spoke to her privately, [saying] you must leave the country, going into exile for two years.”

Health ombud Malegapuru Makgoba has drawn links between the country’s violent past and the LIfe Esidimeni scandal — but he is not the only one who caught a glimpse of history repeating itself, as snippets from testimonies at the recent arbitration show.

Phumzile Motshegwa testifies before the recent arbitration into the Life Esidimeni tragedy. She collected the body of her brother Solly at a former Atteridgeville butchery. (Andronica Nedzamba)

Phumzile Motshegwa lost her brother Solly Mashego

“Solly was my eldest sibling. He looked after us, especially after our father was arrested and served a 15-year jail sentence. It was during a time of turmoil in South Africa. The Inkatha Freedom Party was at war in the townships.

“One day, Solly was on his way to see his girlfriend. As he got off the train, he was hit on the head with a hammer. After that incident, Solly became mentally disabled. He couldn’t do anything for himself.

“At Life Esidimeni, he received the best care.

“I was never told that Solly was being moved to an NGO. I received a phone call that he died in November 2017. “When I asked where should I fetch him from, I was given an address of Precious Angels. It is so close to where I live, but no one told me that my brother was close by.

“I went to identify his body at the mortuary where Precious Angels’ owner Ethel Ncube said she kept him. When I got there I recognised this place. It felt so familiar. Then I remembered: This was the butchery we used to buy meat from when I was in high school.

“I went inside and they brought two bodies to identify, one was a woman, and the other person wasn’t Solly. Then they brought Solly in, naked like the other bodies. There was another body stacked on top of him. I took the blanket I’d wrapped myself with and covered him with it. I had to protect his dignity. I want to tell the government that they don’t live up to their Batho Pele principles, that people come first.”

‘My brother loved food with a passion’: Christopher Mogoerane (right) died after being transferred from Life Esidimeni facilities to the Rebafenyi Centre outside Pretoria. The centre did not have enough food to feed patients.

Lucus Mogoerane lost his brother Christopher Mogoerane

“Christopher loved food with a passion. I always bought fruit for him whenever I visited him. But when he was a patient at Life Esidimeni, I did not have to worry [about] him being hungry. “I was informed a day before he was moved to the Rebafenyi Centre outside Pretoria that he was being transferred. I went to visit him there and he had lost a lot of weight.

“When he saw me he started crying like a baby. I gave him and some other patients bananas that I had brought. They were so hungry, they ate them with the peels still on. I asked the owner of Rebafenyi if there was food for the patients.

“She confessed that there was none. She said she’d taken patients in because of the money she would get from the health department.

“Like I said, my brother was a food lover, and that was my biggest concern about the facility — the lack of food. After two weeks at the NGO Rebafenyi, my brother died because of the concentration camp-like conditions.

“This death toll from this tragedy is four times that of Marikana. South Africa has the most beautiful Constitution in the world. Our government should live up to it and protect the vulnerable.”

Joseph Gumede lost his life at the unlicensed NGO the Anchor Centre in Cullinan. His family was unable to perform last rites on his body because they were only notified of his death seven months later.

Ntombifuthi Dhladhla lost her brother Joseph Gumede

“My brother was transferred from Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital to Life Esidimeni in 2015. He looked very handsome when he was at Life Esidimeni. I last saw him in December 2015.

“I wish I took him home with me that day. I thought I brought my brother to a safe place, but I signed off on his death. For months I didn’t know where my brother was. I went to the office of the department of health to ask about his whereabouts. No one knew. I was told that my brother died in July 2016 when a social worker came to visit my home in February 2017. “He had been placed at Cullinan’s Anchor Centre and died there.

“My sister and I went to identify his body. The smell was unbearable. I could hardly recognise his face. The only thing that made me certain that this was my brother was his missing legs — both his legs had been amputated.

“We travelled back home with his corpse. Flies filled the van. Every time we approached a robot, I prayed that it would be green because every time we stopped at a red robot, flies from his corpse would come to the front. We struggled to breathe because of the smell.

“The next day, the undertaker called me to tell me that they can’t dress my brother because worms were coming out of his body.

“We couldn’t perform rituals that we normally do when loved ones die. I can’t look my family members in the eye because I am the one who sent him to Life Esidimeni. I will never forgive Qedani Mahlangu. I won’t rest until justice is served.”

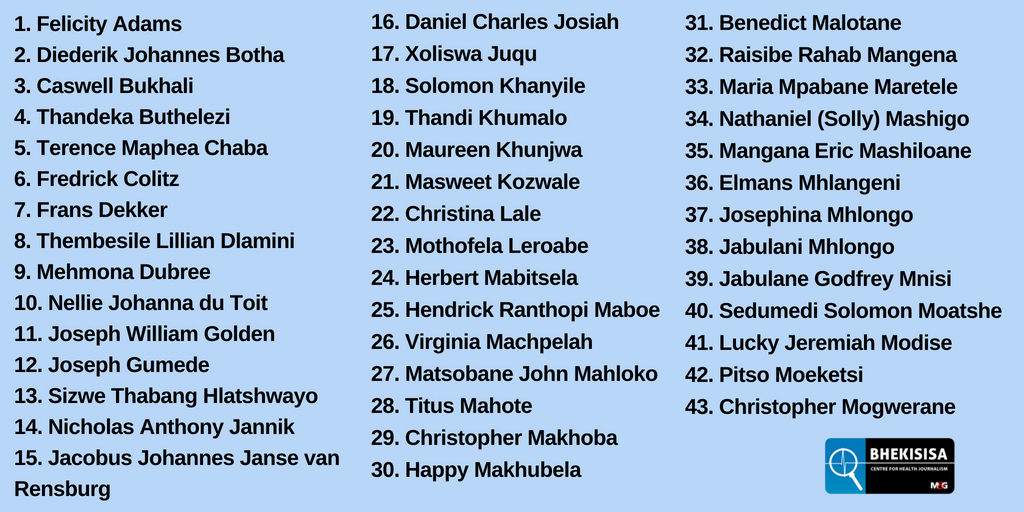

Say their names: Only a fraction of Life Esidimeni patients involved in the tragedy are publicly known.

Elizabeth Phangela lost her brother Christopher Makhoba

“Christopher had been a patient at Life Esidimeni since 2001. We didn’t know where he was moved to until his death. Ethel Ncube of the Precious Angels NGO called us and informed us of his death — almost two weeks after he had died. She called to ask if her organisation could bury my brother. She wanted us to use her undertaker called ‘Put U to Rest’. When we went to fetch him at the mortuary, a worker there said to us, ‘here’s your brother, you can check him if you want, we didn’t cut anything’. Ethel forced us to pay the mortuary owner for the storage fees.

“My brother was wearing burnt tracksuit pants, mismatched socks and a vest that had a missing sleeve. We wanted to collect his spirit, and so we made arrangements to meet Ethel to show us where he died. She didn’t show up.

“I don’t see this tragedy as anything like Marikana [to me it is worse]. Miners went prepared with weapons. Patients were vulnerable. [When they were sent to those NGOs, it’s like] they were abandoned in an open field. They were killed.”