Instead of maintaining a strict interpretation of the borders of all times, flexible regulations regarding usage of the waters are sometimes put in place. (Picture Alliance)

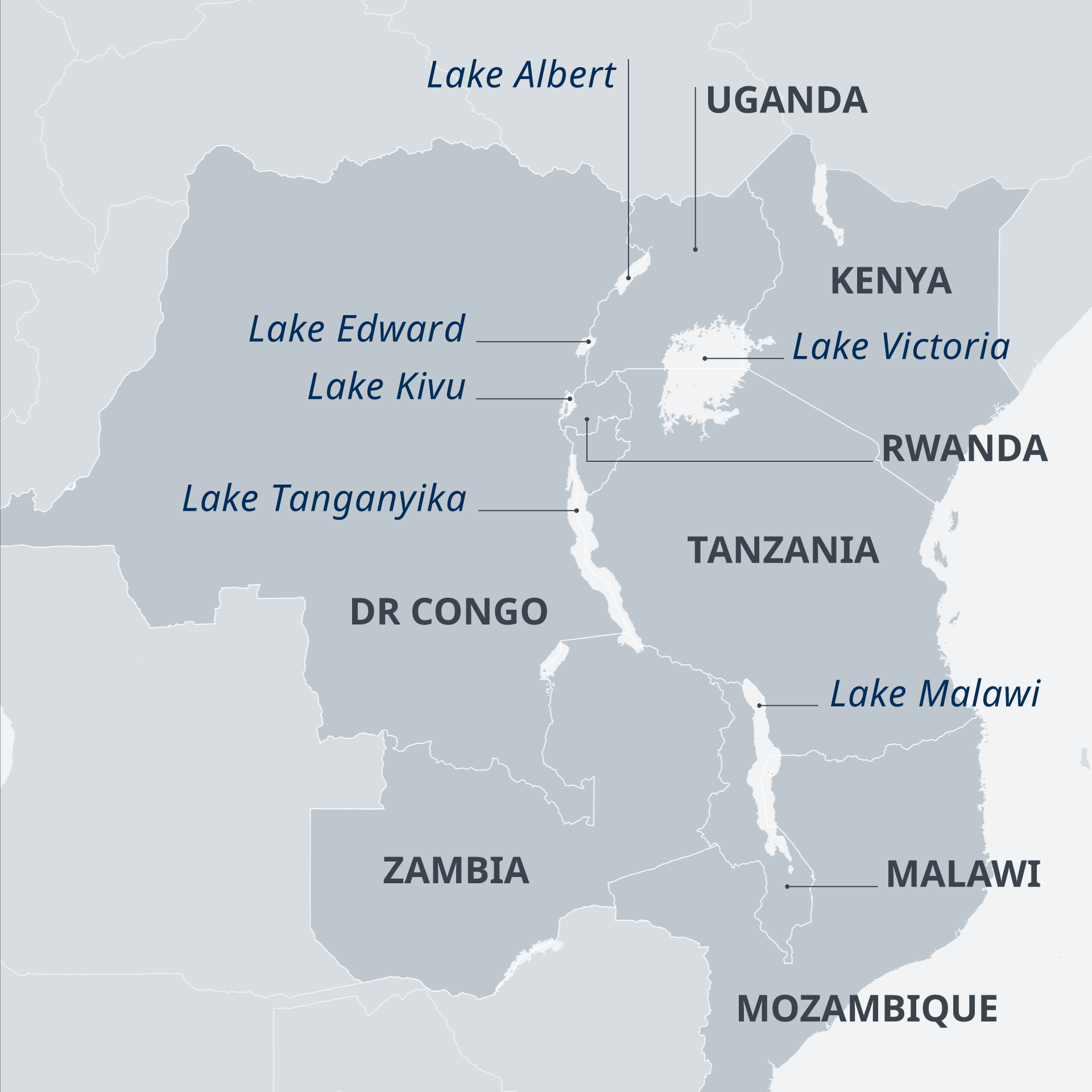

“The border is not visible on the lake,” a Congolese fisherman says. “You can see it on the land, but not on the water.” He works on Lake Edward, which is lies between the Uganda-DRC border. He says soldiers have created a business-of-sorts here by forcing fishermen across the invisible border and then imposing a hefty fine. Richard Karemire, a spokesman for the Ugandan army, says there is no conflict with the so-called “friendly troops” from the neighbouring country. Rather, at the heart of the problem are the people who fish illegally.

In early July, Ugandan soldiers fired on Congolese fishermen on Lake Edward, following alleged clashes with the Congolese army. Thirteen of them were killed and 92 more arrested, according to reports from the DRC side of the border. Negotiations between the two countries continued without a satisfactory result. Further north, they share another border along Lake Albert. At the end of July, a Ugandan court sentenced 35 Congolese fishermen to up to three years in jail for illegally fishing in Ugandan waters.

Taxes, resources, and refugees fuel disputes

The tension along the Ugandan-DRC lake border is symptomatic of the entire Great Lakes region in East Africa, says Phil Clark, an expert on Africa from SOAS University of London. “This is a time of extreme economic pressure in Uganda and the central government is beginning to feel this,” he continued. “And so the government is worried about losing tax revenue off fishing enterprises in those two lakes.”

In addition to this, there is also an ongoing dispute concerning recent oil discoveries in the Lake Albert basin, while tens of thousands of refugees from DRC’s embattled north-east region have crossed the lake seeking safety in Uganda, causing further tension there.

This conflict can be traced back to the colonial era. “The area around these lakes — Lake Albert and Lake Edward — used to be united, and it was the Europeans who divided it up,” DRC Ambassador in Uganda, Jean-Pierre Masala, says. “If there is a dispute, the regional leaders need to govern the area.”

A colonial legacy

The colonial power artificially drew the borders between the states — and often along the lakes — explains Clark. As a result, there is a higher potential for conflict in the border regions today. In the ongoing dispute over their claims to land and resources, some states still invoke this colonial-era demarcation.

Malawi, for example, is entitled to claim the entire northern half of Lake Malawi on the border with Tanzania, according to an agreement dating back to 1890. At that time, Germany conceded the entire body of water to the British territory — today known as Malawi. However, this deviates from another common understanding of the law, which states that the border should be drawn in the middle of the lake. So far, threats to bring the dispute before the International Court of Justice have not materialised. Some observers have been pushing for an out of court settlement — however, the recent discovery of oil beneath the lake has only complicated matters further.

But there’s another big problem, according to Clark. “One other crucial factor is the way that the colonials drew these borders so that they typically placed the capital city quite a long way away from these borders, and so there is a big question about state authority and the ability of central governments to control those borderlands.”

In the dispute over regional hegemony, border controls serve as a demonstration of a country’s strength — as seen in the dispute over claims on Migingo Island on Lake Victoria, where Ugandan forces shut down a Kenyan-owned kindergarten on the grounds that it could not stay open without consulting with the Ugandan government. Both countries claim the island for themselves, with Ugandan and Kenyan police occupying the island at various times.

‘Fish do not comply with international law’

Instead of maintaining a strict interpretation of the borders of all times, flexible regulations regarding usage of the waters are sometimes put in place. Francisco Mari, an adviser on world food, agricultural trade and maritime policy, advocates for the sharing of resources.

“Fish do not comply with international law,” he says. For example, if fish prefer to spawn on certain shores of the lake but can’t be caught there, controls could become more transnational by setting up catch quotas and limiting the number of fishing boats from both countries rather than maintaining strict border surveillance.

This was how things worked on Lake Victoria until recently. “Everyone was allowed to fish as long as he was registered and paid two days’ catch worth in taxes,” Mari says. This system was regulated by the fishermen themselves, through an association known as Beach Management Units (BMU). “If these units are able to control themselves, including when and how much is fished and under what conditions — such as only using coarse mesh — they are able to secure their own interests, because they want their children to live off of fishing as well,” says Mari.

However, complaints soon arose accusing some members of the BMUs of illegal fishing and corruption. Uganda responded by abolishing all BMU’s from operating it its region — as well as on Lake Albert and Lake Edward — which is now patrolled by the army. Over the course of a year, hundreds of fishing boats were burned and many nets destroyed.

Some fishermen welcomed this turn of events, as it allowed fish stocks which were being threatened by overfishing to recover. However, many would like to see a return to self-governance. Mari cautions against imposing overly strict measures on fishermen in the area who rely on the lake for food. “Under these poverty conditions, fishing for subsidence must be allowed to continue,” he says. “For example, women should be able to drop their nets from the shore, or else there is a risk that even more poverty and hunger will persist.”

Handling a potential conflict ahead of time

Ironically, Lake Kivu, situated on the conflict-ridden border between DRC and Rwanda, has come the closest to finding a solution to these kinds of resource disputes. Several years ago, the lake was found to contain huge quantities of methane gas. Most of the gas was found on the Rwandan side of the lake, but both countries have profited from the discovery.

“We’ve seen that the constant flow of high level officials back and forth across that border trying to ensure that resource management is coherent and that conflict doesn’t spill across that border,” says Clark. In this case at least, the long history of conflict on both sides has served as a pre-warning to the dangers of mismanaging the situation. — with additional reporting from Alex Gitta, Emmanuel Lubega and Veronica Natalis