Digital community: ReadingZimbabwe.com founders Nontsikelelo Mutiti and Tinashe Mushakavanhu. (Photo: Dominique Sindayiganza)

Brooklyn is not an obvious inspiration for an archival project about Zimbabwe. In a modest brownstone in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Nontsikelelo Mutiti, hosted sadza parties, opening her living room to friends and strangers, a motley crowd of young creatives — visual artists, photographers, writers, filmmakers, musicians, journalists, academics.

There was no VIP. Everybody was equal, held together by words, music, and food. And there was always drink to lubricate the gatherings. She invited passionate people to meet other curious like-minded people. It was always an exceptional crowd of handpicked guests. There was no regularity nor were the cast the same but the occasions were memorable. It was quite an eclectic mix: Shabazz Palaces, the American hip hop duo of Tendai Maraire and Ishmael Butler; Cameroonian Ntone Edjabe, founding editor of Chimurenga magazine; Zimbabwean graphic designer Saki Mafundikwa; Daniel Kaufman, American director, producer and screenwriter; Brooklyn artist LaKela Brown; Essence magazine’s Natasha Hatendi; journalist Siddhartha Mitter; artist Richard Mudariki.

The conversations and laughter were animated and certainly drifted and echoed through Brooklyn back to Africa. Sometimes the discussions briefly went out into the street as people puffed cigarettes sitting on the stoeps just as we used to watch in old African-American sitcoms. These nights energised and inspired a search for meaning, for stories that defined who we are, where we come from. Although subjects such as Donald Trump and #BlackLivesMatter were more urgent existential issues for a group of young black and African immigrants living in the United States, Africa (and in our case, specifically Zimbabwe) consumed us.

I was introduced to these gatherings via Facebook and joined in the mix as ‘a friend of a friend.’ New York is a vibrant intellectual environment but to find a community of young people of colour nourishing each other intellectually and emotionally was invaluable. The conversations were never prescribed and no one could predict the nature of each conversation.

Zimbabwean history, however, preoccupied our imaginations and curiosities. The enduring question was: At what point does history begin and who is telling our history?

Zimbabwe is a curiosity to people who aren’t from there. Too often, the first question people ask, before inquiring about your health or other such pleasantries is: How is Mugabe or the new guy?

But there is another Zimbabwe, one that exists as if former president Robert Mugabe and current President Emmerson Mnangagwa are tourists who have overstayed their welcome. A Zimbabwe that is full of people who do things, make things, a people who face the country’s contradictions daily and are determined to make good with little or nothing.

There is no easy answer to Zimbabwe’s problems. Together with Mutiti, an industrious university professor and artist, we embarked on mapping Zimbabwe’s intellectual and publishing histories.

We were quick to observe that the Zimbabwean national archive is threatened with extinction: many of the key books of Zimbabwe’s literary canon, for example, are out of print and most young people in Zimbabwe have no way of knowing they even exist. We set up what we thought was a simple website to document books about Zimbabwe.

Reading Zimbabwe, as a digital platform, was established in late 2016, a year before the removal of Mugabe, to think about and represent the country differently. Though we had no funding or institutional support, the urgency of the task spurred us on.

Mugabe’s hold on the Zimbabwean imagination for almost four decades necessitated the need to create a new set of questions, new practices and methodologies that allow us to harness the inventiveness, the generative resilience and the agility of Zimbabwean society.

In effect, Reading Zimbabwe, reanimates the archive. We chose not to sit back and condemn but rather to mine the past for information about the present and the past.

Reading Zimbabwe adopts a participant model of provenance that expands the definition of record creators to include everyone who has contributed to the record and has been affected by its action.This gives control and oversight to people who are treated as subjects of colonial government records with lesser claims to and rights over those records.

The historical records of Zimbabwe still reside primarily in Britain and the US, and young Zimbabweans have had limited access to the primary sources of their history. This has affected their ability to write their own history and to (re)construct their collective memory.

Reading Zimbabwe touches on generational disconnect and is equally concerned with understanding and intervening in the larger histories among which we must situate our identity.The project addresses the colonial archive as much as it questions memory by bringing many contradictory texts into dialogue with one another.

It is a predicament of modern Zimbabwe that its young published history is receding from view. The country’s written literature symbolically begins in 1956 when three intellectuals —Ndabaningi Sithole and Herbert Chitepo (founder and leader respectively of the Zimbabwe African National Union) and Solomon Mutswairo —produce the first vernacular books in Ndebele and Shona.

This represents the first time black Zimbabweans could write and publish books in their vernacular languages. But to be a writer, even in vernacular, black Zimbabweans, had to publish overseas. The first books were smuggled out of the country and printed by presses such as Oxford University Press or Longman in Cape Town. The Rhodesia Literature Bureau in partnership with the Catholic Press (later known as Mambo Press) were only set up a year later in 1957, which had a huge effect on vernacular publishing in Rhodesia — almost 200 books in Shona and Ndebele were published between 1957 and 1980.

Black people in Rhodesia were not actively encouraged to write in English. Nor was higher education. The marginalisation of black intellectuals became unofficial policy after 1965 when the government pronounced the Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) from their mother country, Britain. The devastating consequences of UDI on black intellectual traditions have not been adequately scrutinised. The isolation from the rest of Africa at a period of rapid decolonisation, the limited fruitful contact between black intellectuals and their peers on the continent, has had adverse effects on Zimbabwe’s post-independence development.

In most of Africa’s influential journals published in the 1960s and 1970s there was little or nothing from black Rhodesia. It was the silent decade when black Rhodesia’s intellectual freedom was muted by a rogue white government.

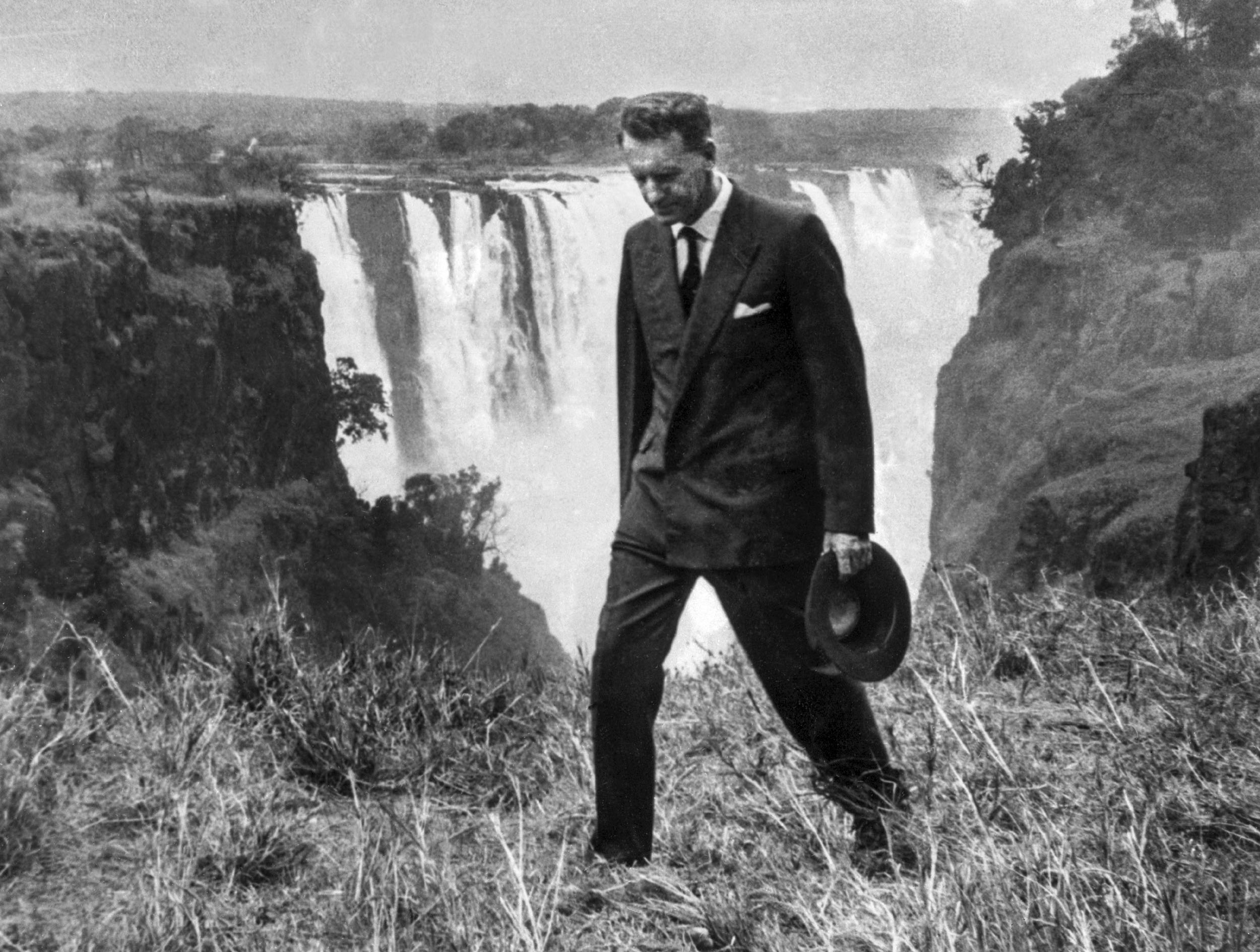

[Prime Minister of Rhodesia Ian Smith, walking near Victoria Falls in 1965 (Photo: AFP)]

[A picture taken on February 6, 1980 shows members of the black nationalist guerrillas of the Zimbabwean African Liberation Army (ZALA), staging a rally in an unknown place in Zimbabwe. (AFP)]

And then in the 1980s there was a burst of creative expression in Zimbabwe. But when Mugabe changes the constitution to become an autocrat, the tenor of the national narrative dramatically changed. Independent journalists were abducted and killed, vocal critics were driven out of the country, intellectuals and writers were pushed to conform or leave and repressive legislation was passed.

[A picture taken in March 1980 shows then Zimbabwean Prime minister and leader of the ZANU party, Robert Mugabe, giving a speech in Harare (AFP)]

Despite the ubiquity the internet promises, it is hard to locate Zimbabwe. Material about the country is scattered online.In many instances, a lot old Zimbabwean texts have no information or descriptions, especially those written and published in the vernacular.

One of the challenges for Reading Zimbabwe has been: How do we archive gaps; how do we acknowledge the absence of texts? Many of these texts have long since been out of print and have become hard to find. The title, or name of an author becomes a precious clue to a book’s existence. As these books have become rare, and can generally only be acquired through an online auction,they are expensive. Buying these books is a luck of the draw —no covers, torn, autographed to past owners, discarded library copies.

Reading Zimbabwe is personal and political —we are beginning to witness a new thing, especially since the removal of Mugabe — and this searching disaffection has everything to do with the liberating potential of new technologies.

Young Zimbabweans are looking for a language of resistance and a way of expressing opinions in a historically controlled society. Zimbabwe remains superficial. People don’t want to dig deeper. They are afraid to go to deeper levels. They refrain by saying zvakaoma (it’s hard) or zvichanaka (it shall be well).

Visit readingzimbabwe.com