Boost: The Soubre hydroelectric dam, built by China to reduce the energy deficit in Côte dIvoire. Other countries in Southern and Eastern Africa are also looking to hydropower.

There isn’t enough electricity in sub-Saharan Africa. Industry can’t grow rapidly and many people have to use paraffin and firewood for cooking and heating. To change this situation, the African Development Bank says generating capacity has to grow by 6% a year by 2040.

As of now, sub-Saharan Africa has 170 gigawatts of energy capacity. That’s as much as Germany’s. A quarter of that capacity is in South Africa alone.

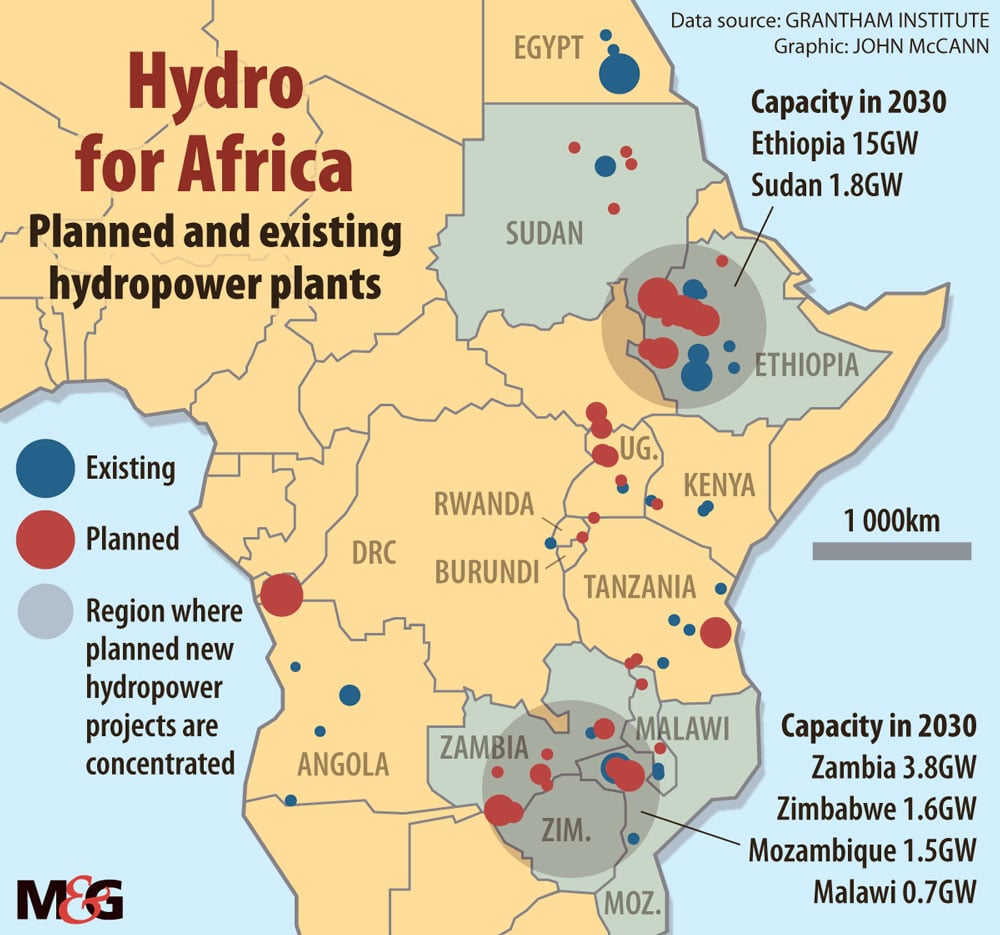

South Africa has a lot of coal to burn in coal-fired power plants. Other countries in Southern and Eastern Africa don’t have this source for energy. But what they do have are big, long rivers with a steady flow. Some 27GW are already being produced in these regions and they want to build an extra 31GW of hydroelectric power by 2030. That doubling of capacity would go a long way to solving the electricity shortage.

But this is a big gamble. That’s according to new research from Britain’s Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment. Its brief for policymakers — “climate risks to hydropower supply in Eastern and Southern Africa” — looks at the effect of the 43 big hydropower plants being planned in these regions.

The brief focuses on rainfall. A shift in rainfall is the most obvious effect that global climate change will have on the continent. Predictions are that the east will get hotter and wetter and the south will get hotter and drier. That will mean up to 20% more, or less, rain falling each year. When that rain does come, it will be in shorter and heavier bursts.

Dams don’t cope with variable rainfall. The turbines are built to operate with a certain flow of water going through them, so when there’s no rain, there’s no power.

Zambia has already experienced poor water flow. The country has 2 800 megawatts of installed electricity capacity. Almost all of the country’s power comes from its hydroelectric schemes. In the past this has given Zambia an electricity surplus. But then came El Niño and a crippling drought in 2015 and 2016.

Water stopped falling from the sky across the Zambezi catchment, which meant barely a trickle entered the Kariba Dam. By January 2016, water levels in the dam were down to 12%. Any lower and there wouldn’t have been enough water to flow into the turbines in Kariba Dam’s wall. The country’s energy utility lost 7% of its capacity as the turbines throttled back. Load-shedding started. This hammered the capital Lusaka and the industrial copper belt, the heart of Zambia’s economy. A combination of the drought, load-shedding and a global drop in the price of copper cost the country 19% of its gross domestic product that year.

The Grantham brief says: “In light of unpredictable climate change and potentially heightened rainfall variability, increasing reliance on hydropower could pose significant risks to security of supply.”

What’s really worrying for the researchers is that the majority of the new plants will be in two river basins: the Nile and the Zambezi. This concentration increases the risk that flood or drought will knock out a big chunk of power supply. “Within each region, the majority of hydropower plants are currently reliant on areas of the same rainfall variability and will continue to be so,” says the report.

Some 80% of the new hydropower in East Africa will be along the Nile, while 89% in Southern Africa will be along the Zambezi River. In the 17 countries where hydropower already provides 20% of the electricity, this means failure of this source of energy will have a big negative effect on these countries.

If the plants do go ahead, the brief says the different parts of Africa need to connect their electricity grids. This will help mitigate problems when one region’s power isn’t working. That could give some security to countries and their economies as rainfall patterns become unpredictable.