Kenyas Raila Odinga is often described as a populist but his manifestos reveal the policy concerns of a social democrat, although his campaigns have populist elements and have coalesced over popular grievances. (Marco Longari/AFP)

COMMENT

In August, Ugandan musician turned independent politician Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu, better known as Bobi Wine, went to campaign on behalf of Kassiano Wadri, another independent leader who was contesting a by-election in the Arua municipality.

Wine’s aim was to use his own popularity to help a like-minded colleague into power — and in the process deal a symbolic blow to the regime of President Yoweri Museveni.

During the election, Wine’s energy, charisma and message resonated with those who have grown tired of Museveni’s 31-year rule and are impatient for change. Fearful of Wine’s growing support base and influence — which was confirmed when Wadri won the seat — the National Resistance Movement (NRM) government detained and tortured him.

Ugandan politician musician Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu, aka Bobi Wine, was tortured by security officers for his opposition to President Yoweri Museveni. (Eric Baradat/AFP)

Some commentators have described this crackdown as an unnecessary overreaction and asked why Museveni was willing to attract so much international criticism over a by-election for a Parliament that his party dominates. The answer is that it was not the Arua municipality by-election that was keeping Museveni up at night.

His concerns have much deeper roots, namely that urban areas overwhelmingly support the opposition, and this trend is likely to be exacerbated by Wine’s emergence as a national player.

The NRM’s lack of popularity in towns and cities has not mattered that much up to now, because Uganda is a predominantly rural country and so the president did not need urban votes to stay in power. But as the country urbanises, and as the government seeks to contain public dissatisfaction with Museveni’s transformation into a “president for life”, the strong urban support for the opposition is becoming a greater threat. When old ways of maintaining power become less effective, the government will have to use other tactics to get the job done — which will probably result in an even greater reliance on brute force.

Significantly, this is not just a Ugandan story — instead, the case of Wine reflects broader trends across the continent. Africa is urbanising fast, and as it does so its politics is likely to change in five important ways.

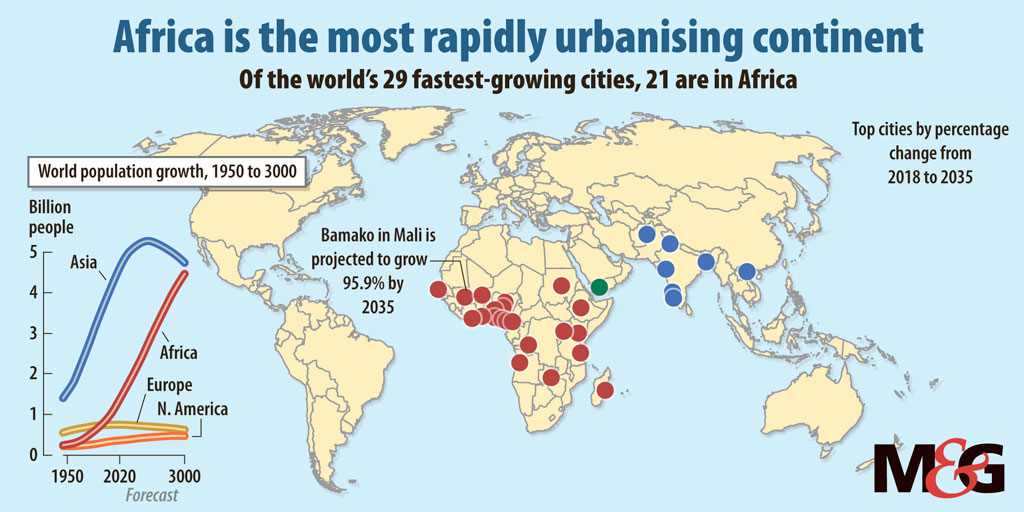

In the 1960s, when colonised countries became independent, Africa was an overwhelmingly rural continent. In the 1990s, when multiparty politics was reintroduced, it was still heavily rural. But by 2040, most Africans will live in urban areas. The speed of this change is remarkable. According to data from academic and author of Party Politics and Economic Reform in Africa’s Democracies Anne Pitcher:“Africa is the continent where urbanisation has grown fastest since 1990” and 21 of the world’s 30 fastest growing cities are on the continent.

The long-term effect of these trends on everyday politics will be far reaching. At present, governments know that they can win elections on the basis of rural votes, and so they target many of their policies at the rural electorate. As a result, the reintroduction of elections has typically made a bigger difference to rural voters than urban ones.

Research by academic and author of Attribution and Accountability: Voting for Roads in Ghana Robin Harding, for example, has shown that in more democratic countries like Ghana the introduction of multiparty politics had a more positive effect on the delivery of services and the standard of living in rural areas than it did for those residing in towns and cities.

But this picture will change as the urban electorate grows. Governments will increasingly have to secure urban votes to stay in power, and this will make them much more sensitive to the needs of those in urban areas, from slum dwellers to office workers.

2) More difficult to rig elections

Although some governments use services to cultivate rural support, others use intimidation and coercion. Because rural voters typically have less access to information, are more dependent on government patronage and are more influenced by traditional leaders, they are easier for ruling parties to bully into submission.

At the same time, government control of rural constituencies, and the fact that it costs more money to campaign in areas where people are more spread out, means that opposition parties struggle to gain a foothold in the countryside — at least, outside of the home area of their leader.

The advantages this gives to the government are compounded by the fact that rural areas are often given a disproportionate number of parliamentary seats. In turn, this helps to explain both why opposition parties do better in urban areas than rural ones in most African countries and why elections in Africa rarely lead to transfers of power.

Things will be very different in an urban-dominant continent because controlling the flow of information will be more difficult. Whereas rural areas continue to receive the majority of news and information via the radio — despite the recent growth of WhatsApp — urbanites have access to newspapers, television channels and social media.

Governments are therefore likely to struggle to control urban voters unless they are willing to make a huge investment to boost their capacity to censor and control the media, police public space and monitor political activity.

3) Rise of populist leaders

There has been a lot of talk about populism in Africa, which is strange because, as political scientist Nicolas van de Walle recently remarked, in reality there are few successful populist leaders on the continent. Michael Sata of Zambia was clearly a populist in terms of his rhetoric and campaigning style, and the Economic Freedom Fighters’ Julius Malema is doing a good impression of one in South Africa today. But that is pretty much it.

Kenya’s Raila Odinga is often described as a populist but his manifestos reveal the policy concerns of a social democrat. And while it is true that his campaigns have populist elements and have coalesced over popular grievances against the government, these are constrained by the centrality of ethnic solidarity to electoral appeal.

One reason that more leaders have not adopted populist strategies is it is not clear that you can win elections on the basis of populist appeals alone. But this calculation is changing every day. Research by political scientist Danielle Resnick demonstrates that populist messages resonate most powerfully in low income urban areas.

This is significant because rapid urbanisation, combined with the failure of most governments to provide adequate jobs and accommodate for new urban residents, means that the number and size of slums on the continent is increasing year on year, creating a larger potential support base for populist leaders to mobilise. In time, this will create the conditions under which populism can represent a viable alternative to ethnic politics, and will result in the emergence of a many more leaders in the shape of Sata — and Wine.

4) Greater decentralisation

If governments fail to tame urban residents and populist leaders emerge across the continent, we are likely to witness growing tensions between ruling parties and their critics. One side-effect of this is likely to be stronger demands for urban self-government.

While countries like Kenya and Nigeria have already devolved power away from the national level, on the whole African political systems remain highly centralised. If a new generation of urban populist leaders choose to mobilise their supporters around the need for more powerful municipal governments with the capacity to pursue local solutions to local problems, this may start to change.

Governments are suspicious of decentralisation because it threatens to undermine their hold on power. But there is also a well-documented pattern in which leaders facing increasingly robust opposition agree to allow rival parties to wield greater power at the local level in an attempt to deflect pressure for a transfer of power at the national level.

This occurred in Mexico in the 1980s and 1990s, and more recently in multiparty Kenya. If urbanisation strengthens the hand of opposition parties, we are likely to see an increasing number of governments make similar trade-offs moving forward.

5) End of urban/rural divide

One of the most interesting predictions about the way that urbanisation will change African societies is that the physical distance between urban and rural areas is likely to fall in the next 10 years. In addition to the emergence of “urban corridors”, the expansion of regional towns will see them increasingly encroach on the countryside. Along with the flow of remittances from urban workers to their rural kin, and the greater sharing of news and information that will occur as a result of the further expansion of WhatsApp, Twitter and Facebook, this will further erode the urban/rural divide.

The literature on this topic provides us with a valuable warning not to overstate the extent or significance of this divide at present. We already have examples of countries like Zambia where some rural residents share the concerns of their urban counterparts as a result of histories of urban-rural migration and shared narratives of exclusion. But such cases are not that common: if the changes predicted come to pass, the chances are that in time they will go from being the exception to being the norm.

The future

Exactly how these trends play out will depend on the rate of urbanisation and how governments choose to manage this process. Africa features a remarkably varied set of political systems, and so urbanisation will set in motion a variety of trends across the continent.

Ruling parties will have to decide whether to use reform or repression to respond to the challenges that urban expansion will generate. Because repression is expensive, and will be resisted by opposition parties and civil society groups, this response is most likely in countries in which authoritarian governance is entrenched.

It is in countries like Uganda, Chad and Cameroon, where the security forces are regularly used to settle political disputes, that there is the greatest risk that urbanisation will trigger greater political conflict and — in the short-term at least — democratic backsliding.

By contrast, in states that are more open and democratic, such as Botswana and Namibia, larger towns and cities should lead to increasingly competitive elections and, in time, democratic strengthening.

In this way, urbanisation will contribute to the continent’s growing democratic divide.

Nic Cheeseman is professor of democracy at the University of Birmingham