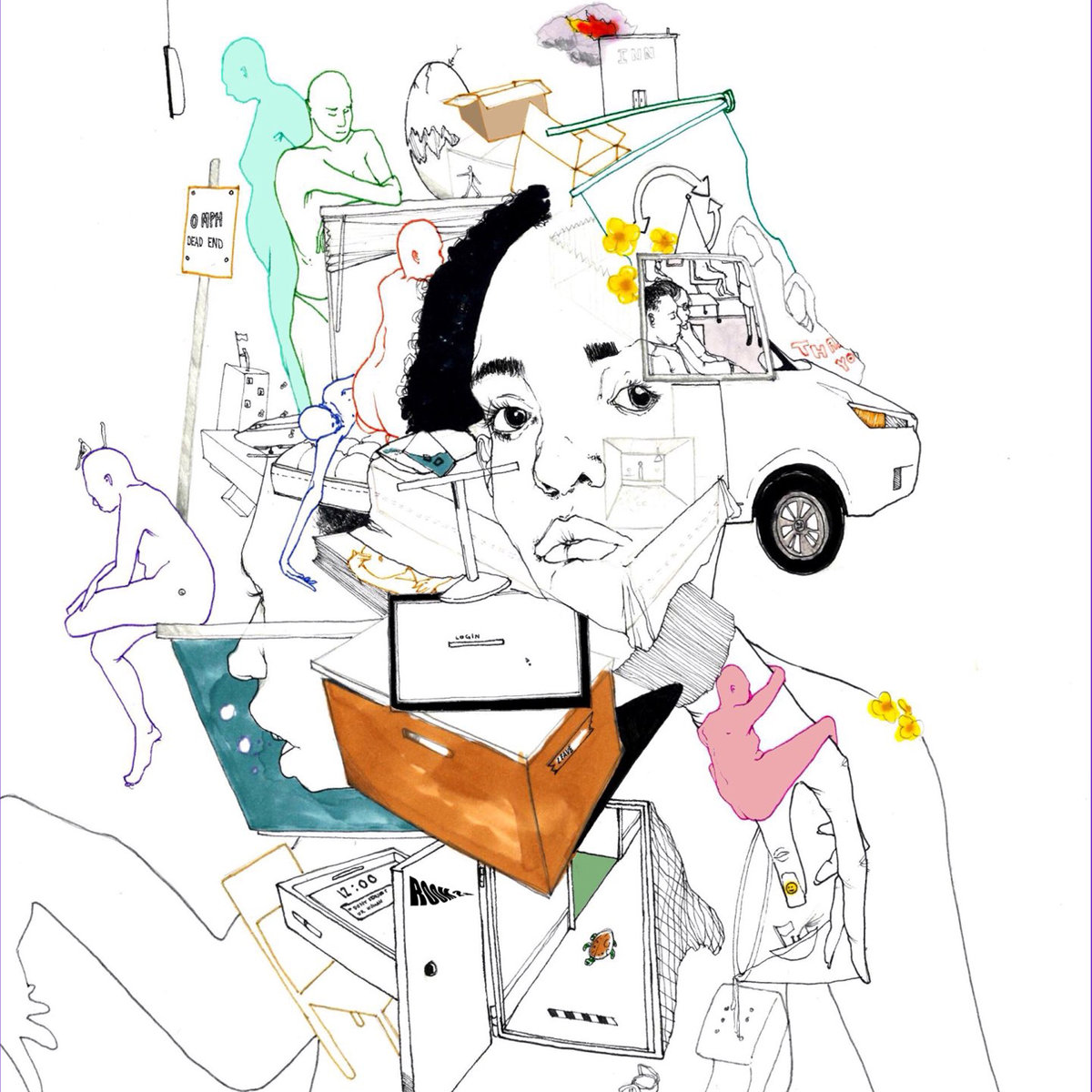

Good pussy: Noname (above) tells it like it is on her sophomore album Room 25 (below). Photo: Jules Ameel

Earlier this month, the low-key 27-year-old rapper and songwriter, Noname, aka Fatimah Warner, released her sophomore album Room 25.

She was born in 1991 in Bronzeville, a neighbourhood in Chicago, Illinois.

Way back in the 1910s to 1920s, a group of African-Americans fled from the oppression in the South to make a home in Bronzeville. The neighbourhood was home to civil rights activist Ida B Wells and musician Louis Armstrong, who played a part in establishing it as a stronghold for civil rights, gospel music, jazz and the blues.

The medley of musical and civil rights influences helped to cultivate Noname’s interests in words during her pubescent years. After a few years of deliberate practice at open mics and slam poetry competitions, her lyrical bud has blossomed into a fruitful career.

This began with a feature on Chance the Rapper’s Lost from the album Acid Rap in 2013. In 2014, she joined Mick Jenkins on the song Comfortable, then 2015 saw her partnering with J Cole and Donnie Trumpet & the Social Experiment on the vulnerable but bold single Warm Enough off the album Surf. And there were many more. Even with her quiet disposition, Noname rarely shied away from the public opportunity to test and sharpen her skills as a lyricist by featuring alongside celebrated names.

In July 2016, Noname released her 10-track EP Telefone, which she says felt like her first time talking to the her listeners over the phone because of the intricate quirks, awkwardness and intimacy that can come with a phone call in the age of texting.

Telefone is a warm-toned audio picture of life in Chicago for a black woman in her early 20s during the mid-2010s. It is as radiant and full of potential as it is tragic and restraining.

Two years have gone by since Telefone. Not only is Room 25 a larger offering but it’s a more earnest record as well. And so if Telefone was about life through the eyes of a young woman in Chicago, Room 25 zooms in to make Noname the sole focus. It’s like an epilogue to Noname’s recently found independence.

[Cover art for Room 25 (Illustrator: Bryant Giles]

After Telefone was well received internationally, the artist spent a lot of her time on tour and living in Los Angeles. At 25 she left home and moved from hotel room to hotel room — hence the title Room 25.

She opens the door to Room 25 behind a minimal drumbeat and harmonies before welcoming us with a suggestion: “Maybe this the album you listen to in your car/ When you driving home late at night/ Really questioning every god, religion, Kanye, bitches.” We bob our heads on cue and just as we get comfortable Self threatens to turn into a nonchalant clapback to Noname’s naysayers when she pokes fun at them for thinking she “couldn’t rap, huh”. The song then unfolds into a quick tour of the growth Noname has had between Telefone and Room 25.

“My pussy teachin’ ninth-grade English/ My pussy wrote a thesis on colonialism/ In conversation with a marginal system in love with Jesus/ And y’all still thought a bitch couldn’t rap huh?/ Maybe this your answer for that good pussy/ I know niggas only talk about money and good pussy.”

This Noname is playfully vulgar and unafraid of criticising her peers. She no longer relies on euphemisms to tackle difficult issues or to confess her convictions. This tell-it-like-it-is theme seeps from the first track all the way to the closing track.

Throughout the album she touches on subjects that include a dark comical look at the state of affairs in the United States, casual safe sex, the pressure that comes with making and the dull poke from insecurities.

Noname manages to highlight and celebrate these themes without the biased self-cleansing or righteousness that can come with narrating your own story. Instead, she acknowledges what the world may view as flaws and problematic standpoints with lyrics such as: “Now I’m swimmin’ in the money with a ducky or 2/ Reading Toni Morrison in a nigga canoe/ ‘Cause a bitch really ‘bout her freedom ‘cause a bitch suckin dick in the new Adidas/ And yes and yes, I’m problematic too.”

This allows the listener to connect with her because, although the idea of an immaculate idol with a blemish-free life may be appealing to consume, a more holistic truth transcends superficial connections.

After having a hand in Telefone, Phoelix, a rapper, producer and good friend to Noname, assumed the role of executive producer on Room 25. In his hands the background to Noname’s bars hop between classic boom bap hip-hop, piano-heavy neosoul and jazz sounds all the way to experimentations on the guitar that make my South African ear fantasise about what maskandi funk could sound like. Having worked with her before, Phoelix is able to match the soundtrack to her muted vocals or scampered syllables to ensure that, while each track has a life of its own, they are able to sit together as seamless furnishings in Room 25.

In Blaxploitation, Noname’s commentary about the state of affairs in the US, her occasional multisyllabic bars are used in a fast-paced flow that allows her to load a think piece into a brief song without stopping to catch her breath. She does this against a quick loop of drums and bass that serves the purpose of showcasing her skill through the way it submits to her pace.

To usher us out of Room 25, the album ends with a track titled Noname to remind us who it is that we came to visit. Here, the rapper explains why she will remain nameless because: “Only worldly possession I have is life, only room that I died in was 25/ What’s an eye for an eye when niggas won’t love you back?/ And medicine’s overtaxed, no name look like you/ No name for private corporations to send emails to/ ‘Cause when we walk into heaven, nobody’s name gon’ exist/ Just boundless movement for joy, nakedness radiates.”

As a twenty something, my only question is: Is this a confidence that comes with age or with increased recognition?