For the record: A young Kewpie poses on the phone

The day after the opening of the exhibition, Kewpie: Daughter of District Six, Ursula Hansby, Kewpie’s only surviving sibling, says she “was totally shocked to see what happened at the opening. I really didn’t expect that.”

The previous night, more than 400 people, double the expected number, packed the District Six Museum’s Homecoming Centre for the opening of a photographic exhibition detailing the life of one of District Six’s most famous queer people.

Although the former and present District Six residents, activists and members of Cape Town’s queer communities came “to find out more about this enigmatic character”, according to a press release, Hansby was there to pay homage to Eugene Malcolm Fritz, the brother she and the world came to call Kewpie.

Etiquette: Kewpie at the Ambassador Club in District Six, where they often performed

The exhibition features about 100 photographs taken from an archive of 700 prints and accompanying negatives housed at Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action (Gala). The images date from the 1950s to 1980s.

Gala director Keval Harie says the collection is “quite an extraordinary documentation of a history and heritage that isn’t often told”.

Although it is not known who the photographers were, “we know from the way Kewpie was posing in them, Kewpie was critically aware of what these images represented”, he says. This demonstrates Kewpie’s “awareness of the importance of visibility for queer people”.

Often using the refrain “I’m not he, I’m not she, I’m just Kewpie”, the icon clearly identified as what today would be called nonbinary. People who identify as nonbinary prefer the gender pronouns “they”, “them” and “their”.

Born and raised in District Six, Kewpie was a popular figure in the area before apartheid bulldozers tore the mixed-race area down, forcing its black and coloured residents to move to the Cape Flats.

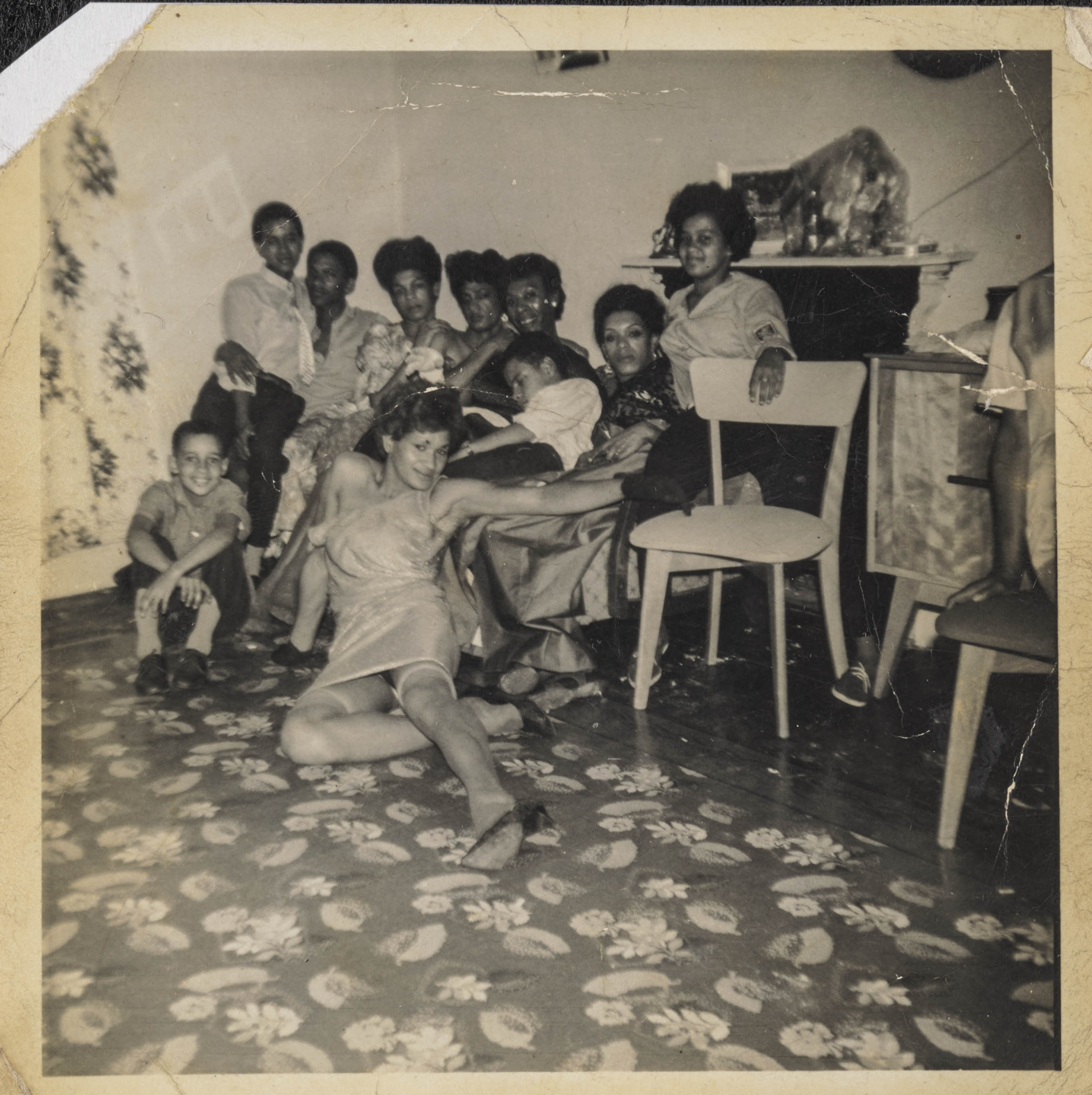

Kewpie with a group of friends at someone’s home on De Smidt Street in District Six

Although Hansby says she “can’t remember how old Kewpie was when it happened — when the change [in Kewpie] came. She adds: “All I can say is my dad was not accepting of this. I think this is because, to him, Kewpie was born as his son. And fathers have some future ideas, I suppose. I don’t know.”

Growing up in a conservative household, “there were strict rules”, she says, but Kewpie had “ways and means of slipping away. I can remember Piper Laurie had a hairdresser on Hanover Street and that was where Kewpie started. That was where he escaped to often and where his hairdressing started.”

Kewpie’s interest in hairdressing piqued, they started bringing clients into the family’s two-bedroom home at 13 Osborne Street. While their father was working his early-morning shifts at a bakery, Kewpie would sit clients down in the tiny lounge, grab the large mirror from their mother’s dressing table and use it while working on the clients’ hair. “Like at a real salon,” Hansby says.

“The first time my dad came home and found this happening, there was big trouble,” Hansby laughs. “But that didn’t stop him. That was his aim in life, I think. To be a hairdresser.”

Eventually they would become a well-known hairstylist, opening Salon Kewpie in Kensington. But they were also a popular performer at District Six’s Ambassador Club.

“Kewpie was a people’s person. He was often in the road. Up until the day he died, there was not a soul that didn’t know Kewpie. He was an entertainer,” says Hansby.

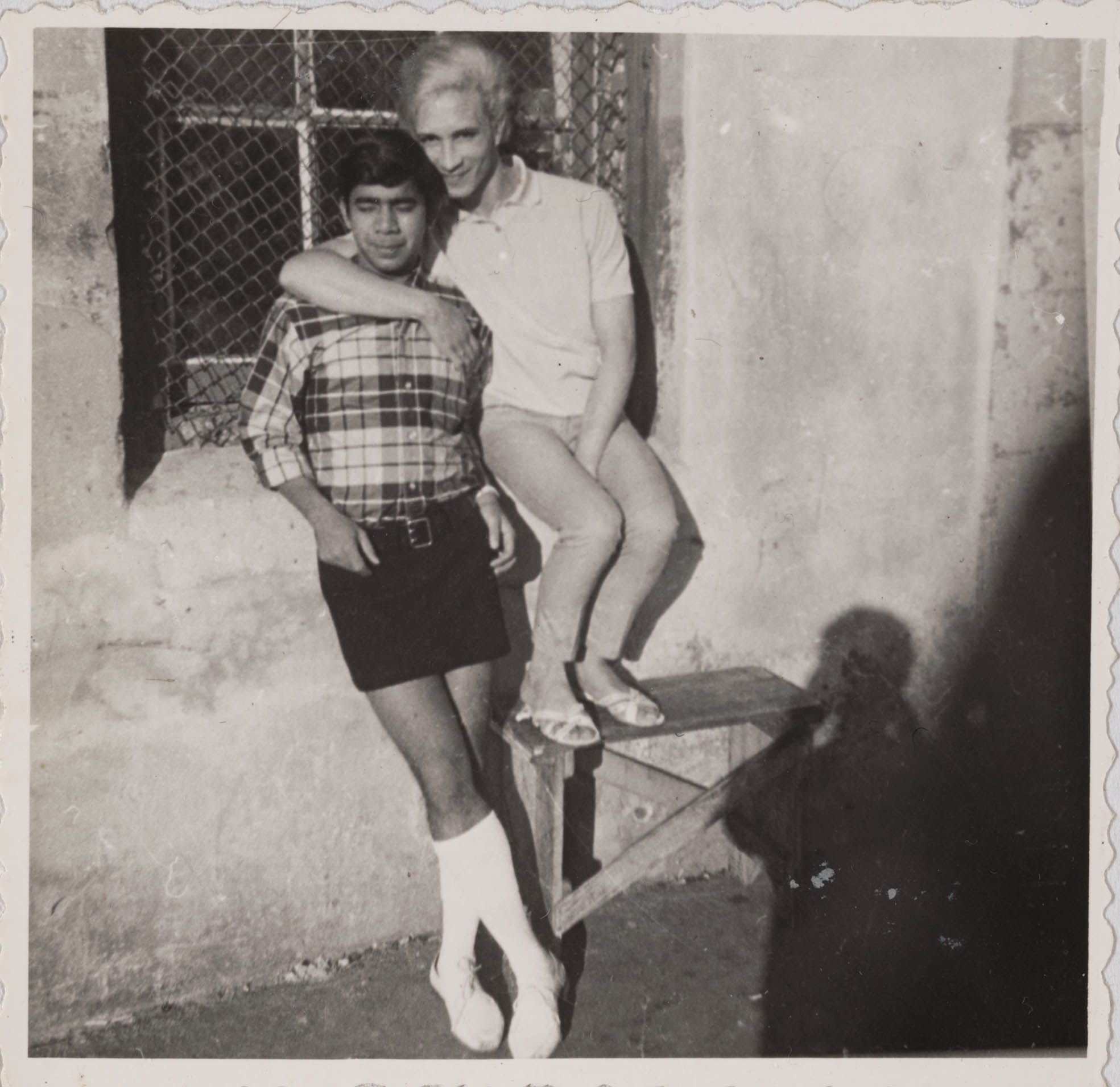

A young Kewpie poses with a friend called Brian on Rutgers Street in District Six

Although appreciative of the respect her brother is being given posthumously, Hansby takes it with a pinch of salt. This is because “so many [of his gay friends] just deserted him” after they developed the throat cancer that would ultimately take his life.

“There are things people don’t know,” she says. “You know, when Kewpie took ill, Kewpie was living with one of his friends. I can’t remember his name. I came from church one Sunday, and there was a car parked outside the house. It was Kewpie that friend of his brought to me. There were only three bags under one of our trees in the garden. That was the only possessions Kewpie had left, after all that he had in life. That was when they came to dump him. Because he took ill.”

The recollection too much for her, Hansby cries. “Kewpie didn’t deserve that life, I feel, in the end. After everything he did for everyone. Kewpie fed everybody that was stranded. He had a small place, sufficient for one person. There wasn’t enough place to sleep but he accommodated people there. And this is what is disturbing for me. He died a lonely person. With nothing. That was the abuse Kewpie got from so-called friends in the end.

“His vocal cords were removed because of the cancer, so nobody had time for him. So we took care of him until the day Kewpie died. We buried him on a rainy, rainy Sunday, I remember.”

It is because of this sense that her brother was betrayed by the ones they loved and cared for that Hansby says she did not want to attend the exhibition’s opening night. “But my husband and daughter insisted I go.”

Once there, and astounded by the reverence for her brother — District Six’s “daughter” — Hansby says she “asked someone: ‘Why Kewpie? Of all the gays of that time, why Kewpie?’ But I think it is because of all the photo albums he had. I think he was the only one that had such a great amount of photos; photos of every occasion and every function.

“But more than that, I think it’s the life that Kewpie had. It’s the kindness — everything he had, he shared. That is important. People were very important in Kewpie’s life. Love flourished everywhere Kewpie was.”

Carl Collison is the Other Foundation’s Rainbow Fellow at the M&G.

Kewpie: Daughter of District Six runs until January 18