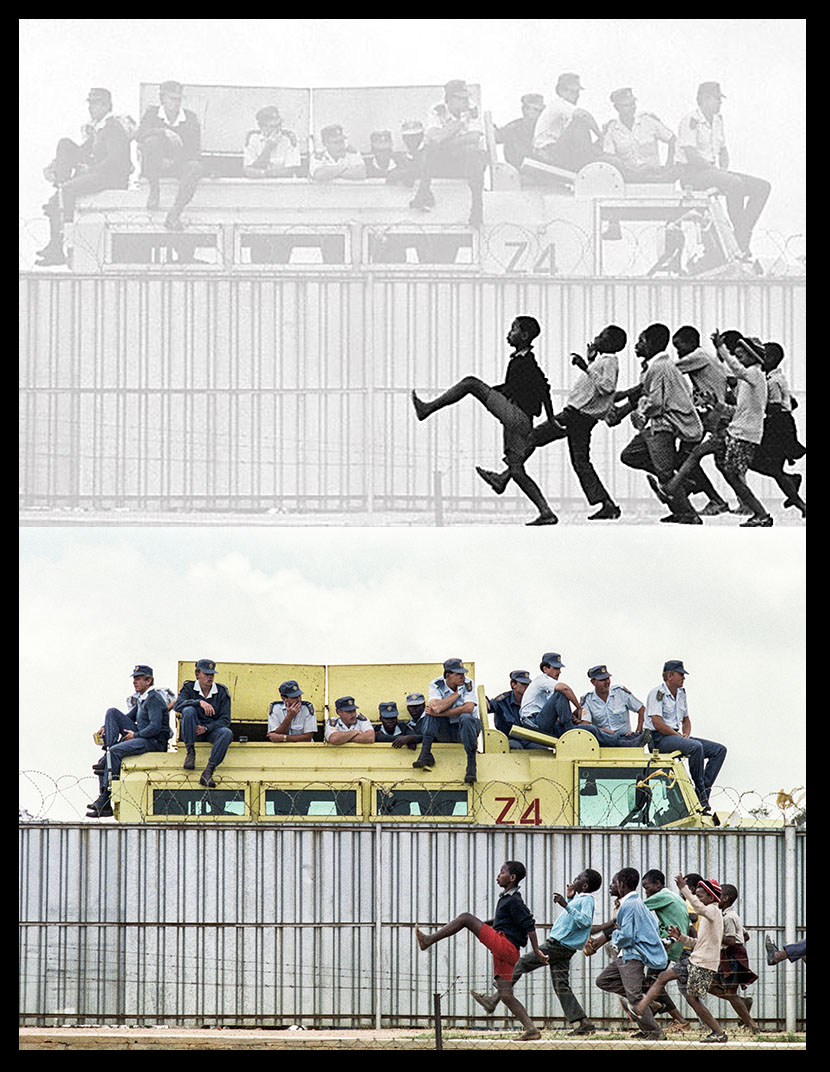

Taken in Thokoza township, Johannesburg, in 1991. The original photograph shows police officers watching an ANC rally while children taunt them from below. (Photograph: Graeme Williams)

LONG READ

M Neelika Jayawardane and Greg Marinovich explore the issues involved in artists’ reasonable or fair use of other people’s works.

Recently, American artist Hank Willis Thomas’s work, Gravitas, in which he made use of a photograph taken by Graeme Williams, was shown by Thomas’s gallery, the Goodman, at the 2018 Joburg Art Fair. The price set by the gallery for this work was $36000.

Hank Willis Thomas’ work Gravitas (above) made use of a photograph taken by Graeme Williams in 1991 (below)

Thomas similarly used photographs taken by Peter Magubane, Alf Khumalo and British photographer Ian Berry (who worked for the Rand Daily Mail and Drum magazine) that depict powerful instances of protest and the indignities and violence that black South Africans experienced during apartheid were also shown at the Goodman. The sources of these photographs were not identified at the booth at the fair.

Thomas later emailed me (Jayawardane), saying that an informative pamphlet introducing Williams’s original photograph and statements he subsequently made about the “gravitas” and power of Nelson Mandela to effect monumental change were meant to accompany his own work. Although the gallery says that the information was provided, it was not given to Williams when he visited their booth, and he did not notice any brochures or pamphlets available for visitors.

Williams did not consent to the use of his work, nor did he know that his photograph was being used by Thomas until he was confronted by the “altered” version hanging in the Goodman’s booth as he walked through the fair. Since then, several articles responding to the ensuing disagreement between the artist and the photographer were published —including mine in Al Jazeera English and Greg Marinovich’s in The Daily Maverick. These articles covered, to various degrees, the politics and ethics of “remixing”, reusing and reframing historical photographs in new artworks. It was clear that neither party was satisfied by the other’s responses. Both wish for their work — and dignity — to be recognised and respected.

It remains unclear what will happen to a number of exhibited works that appropriated other photographers’ works. However, the Goodman produced a statement in which they confirm that the artwork based on Williams’s work has been made unavailable for sale. Following the exposure of the unauthorised use of Williams’s photograph in Thomas’ work, representatives of photographer Peter Magubane came forward making similar claims about the unauthorised use of Magubane’s photographs in the same exhibition, for which the Goodman Gallery also suspended sales.

Knowing Thomas’ track record, and that his artistic practice invites his audiences to be politically engaged, thoughtful consumers, subjects and citizens, I do not believe that he intended to steal the photographers’ works, nor do them dishonour. But I also know that intentions and the effects of actions are two different things.

Moreover, in locations where our cultural, scientific, intellectual and artistic heritage has been erased, stolen and represented as the invention of our colonial masters, it remains important to identify the lineage of our objects and ideas, precisely because we remain in danger of being seen as people who made nothing, innovated nothing and did nothing.

Knowing that the field is a “contentious landscape”, and that there will always be questions about “presentation, representation, ethics, appropriation, commodity, ownership, authorship, exploitation and subjectivity”, as Thomas himself wrote in an email, I invited Greg Marinovich, as a fellow educator and veteran photographer, to think through the issues involved in “reasonable” or “fair use” of others’ works.

Together, we reflect on what might make it permissible for those who do creative work — be they writers, musicians, fine artists or photographers — to reference, sample, riff on and remix, build on and comment on other artists’ works, cultural objects, texts and conceptual frameworks. How might we enjoy the fruits of free exchange in the arts, without exploitation, appropriation or cultural colonisation?

And when the “referencing” becomes less of a homage to the original, a commentary inviting audiences to contemplate politics or ideas that were not as apparent in the original work or a way to reject the cultural norms that produced a certain set of aesthetic values in the original work and instead appears to be an unethical appropriation or theft, then what avenues are available to the creator of the original work to protect their work? In the absence of a clear legal line to identify (and seek redress for) intellectual property theft, we want to open up a conversation about the ethical dilemmas that contemporary artists face.

In conversation

Marinovich: Williams is a contemporary of mine in several ways; we were both among the freelance photojournalists covering the news and conflict at the transition from apartheid to a democracy. We were legally and culturally denoted as white in the sacred racial roll call of apartheid. We lived as white people and enjoyed the benefits, yet we both tried to use our cameras to contest the idea of white supremacy.

When Williams and I were still kids, black photojournalists such as Sam Nzima, Ernest Cole, Peter Magubane, Alf Kumalo and others were already defying the might of the apartheid regime to show the world — and South Africans — the cost exacted on the communal black psyche and body for the benefit of a small minority. That the extraordinarily good life whites were enjoying in South Africa was enabled by the suffering and sweat of others. There were also a few white South Africans who used the camera to expose injustice — David Goldblatt and Eli Weinberg come to mind.

Jayawardane: There was also Jürgen Schadeberg and Bob Gosani, as well as Ranjith Kally and GR Naidoo, who were based at the Drum office in Durban.

Marinovich: They were among the role models for the next generation of photographers —white, black, coloured and Indian — who were moved to document life inside apartheid. This next generation added an Alexandrian library of photographs to the archive of imagery ranging across all aspects of life: the revealing slices of life by Cedric Nunn; the austere reflections of Santu Mofokeng, Gisèle Wulfsohn’s intimate images, the suspended violence in Joao Silva’s photographs.

The list is extensive and varied. Some of that work was always intended to be seen as a body of work in the covers of book, contextualised by the nuance of their chronology. Others were immediate and urgent documents about what was happening that day on the streets. But our world has changed since then: both technologically and economically.

Documentary photography

Marinovich: It’s important to understand that the nature of photography — and what is considered documentary photography in particular — has changed dramatically in the 21st century. The original medium of display has also become less clear. Books are out of print and newspapers shredded and recycled. Some of those images have been revived through digitisation and find their way on to various virtual sites, and in academia or photo agencies’ catalogues. Others are curated on gallery walls. Many images are spun around the world in a dizzying maze of online sites in unauthorised and unrecompensed versions. Even legitimate agencies and sub-agencies sell works for a few dollars in the race to own volume. Value is difficult to preserve; messaging impossible.

The Tate’s documentary photography site explains: “With the rise of television and digital technology [documentary photography] began to go into decline but has since found a new audience in art galleries and museums. Putting these works in a gallery setting places the work at the centre of a debate surrounding the power of photography and the photographers’ motivations. Their work raises questions of the documentary role of the photograph today and offers alternative ways of seeing, recording and understanding the events and situations that shape the world in which we live.”

For these reasons, there is now definitely a conversation to be had about initial intent and subsequent use/ misuse of these images, by both the original creators, the publications that may own copyright and others drawn to them as a source of artistic inspiration, or simply commercial exploitation.

It is tempting to identify photographers’ complete oeuvres by their better-known works, and thus claim that those images should be contained in a certain realm. That does indeed work for some,but for others it is bewilderingly misplaced. For my era of photojournalists, the decent and principled ones followed an informal set of ethical guidelines. This code of conduct is also used by most documentary photographers. Essentially it is that one does not direct or stage-manage any scene, no matter what (except for portraits that are easily recognisable as a collaboration with the subject).

The follow-on is that no deception with light or retouching may be enacted in the darkroom of yore or with photo software programmes. The captions should be complete and not mislead, either by inclusion or exclusion of facts and information. This can be simplified even further: do not mislead the viewer.

There are many cases of those who breach these guidelines. Some pretend to adhere to them, and others claim not to be beholden by them. There is also a more vague concept of not using the images out of context. Yet as the outlets for photojournalists and documentary photographers have diminished to almost naught, or pay almost naught, those who seek to capture the play of light and shadow on reality have found an audience inside fine art galleries.

Some have embraced this with great success, their gritty works hanging on the same walls that hold conceptual photographic works. The question that should be raised is perhaps this: If the original intention of the photographer, and the understanding of the subjects (if they were given an explanation, or if there was a presumption based on the circumstances) was that these were news images, is it okay to repurpose some of those images for gallery walls, for sale as fine art works?

I am not comfortable with ever putting some of my more violent images in a fine art setting. I hated witnessing these scenes and loathed myself for shooting them, but felt compelled to document what was happening. There are other images that depict violence or the indicators of violence that I feel okay about putting into a different realm. And then I have to examine that instinct — people encouraged/ allowed/ accepted/ put up with me because I was a recorder of that moment in their lives and they thought it should be a part of some kind of historic record, be it in a newspaper or in a library (I think).

Sometimes people were aware of who that particular work was intended for, at other times they presumed or did not give a damn. Are the images I shot on days I was on assignment for a news publication governed differently from those when I was shooting for posterity? And does the subject matter change any of this? I don’t have all the answers, but I continue to work through this. Of course, the majority of my work is not of conflict or violence, but I guess I will forever be linked to that kind of work.

The legal parameters

Jayawardane: Thomas has argued in various interviews that it is difficult to identify whether an image has been altered “enough”: “[He] said to me that he didn’t feel like I had altered the image enough. The question of ‘enough’ is a critical question,” he told art net News.

What, exactly, does it mean to innovate a work, or to “transform” it, conveying a new narrative or message by “re-working” an original photograph? Artists and writers may make “fair use” of another work. When evaluating copyright infringement claims, courts must decide whether the “new” work is “substantially similar” in “artistic expression” (that is, aesthetic choices, composition details, etcetera) to the “original”, and whether the artist has “transformed” or “innovated on” the work in some substantial way.

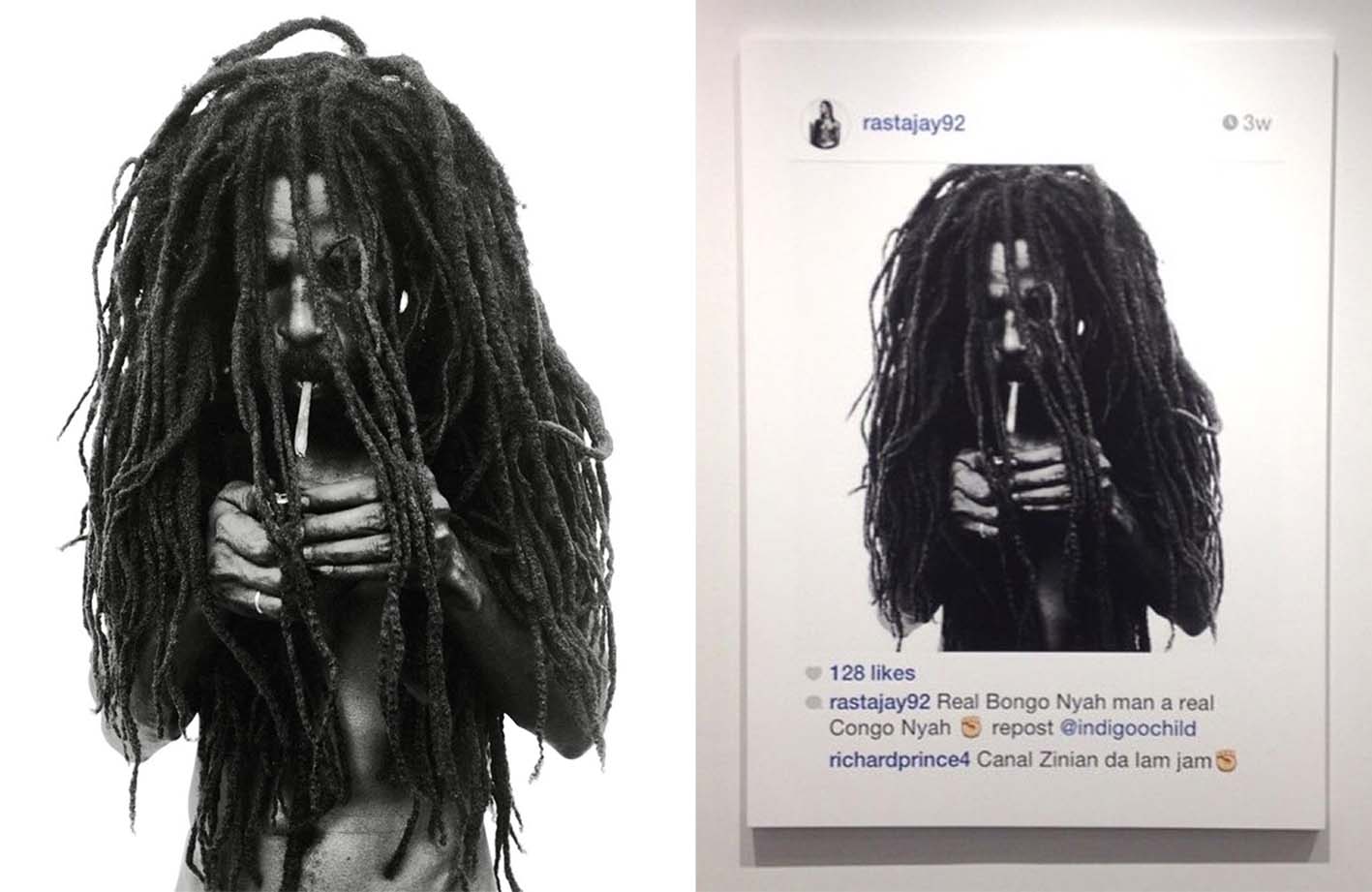

Theft of original photography by artists whose work is intended for the exclusive art market has become a prolific practice. Megamillionaire artist Jeff Koons has been sued multiple times (for upwards of $15-million), and Richard Prince was also recently served with a lawsuit for appropriating Instagram images and showing them — with the original photographs unchanged and used in their entirety — at an exhibition at the Gagosian Gallery in New York. Some of the pieces were sold for up to $10000. United States’ Judge Sidney H Stein ruled, in July last year, that the case would go forward because “the primary image in both works is the photograph itself. Prince has not materially altered the composition, presentation, scale, colour palette and media” that photographer Donald Graham used in his original works.

Pictured on the left is Donald Graham’s work which Richard Prince was accused of appropriating (right).

But unseemly “borrowing” without crediting origin is common in advertising and fashion. Almost every other week, we hear how the director of a fashion photo shoot or a music video “borrowed” aesthetic concepts from artists and photographers from less culturally privileged locations. Pop star Beyoncé is known for “borrowing” striking archival images, dance choreography and costume ideas for videos. For the advert for her 2018 tour On the Run, her team seems to have reproduced, almost to the last detail, the iconic still from Djibril Diop Mambéty’s 1973 classic French New Wave-inspired Senegalese film, Touki Bouki. And her recent Vogue photo shoot looked suspiciously “identical (minus the cat) to the work of a costumes designer duo from Bosnia — Ina Arnautalic and Hatidza Nuhic”, noted artist and writer Sumeja Tulic.

We can keep playing this game: have a look at M.I.A’s May 2010 cover of The New York Times Magazine — a concept she and Ryan McGinley designed — and now spot the similarities to Jennifer Lopez on the March 2018 cover of Harper’s Bazaar.

And advertisers steal stuff from people’s Instagram accounts all the time.

In a far more serious case of intellectual property theft in the arts, M Nourbe Se Philip, a Caribbean-Canadian poet, found that her long poem, Zong! (2008), was used wholesale by Berlin-based contemporary artist Rana Hamadeh. Philip’s work proved lucrative for Hamadeh, who took Philip’s words, concepts and historical research on “a 1783 insurance settlement, in which the owners of the slave ship Zong threw a large number of slaves overboard in order to claim insurance money for the loss of ‘property’ for her operatic art installation, The Ten Murders of Josephine (2017)”, and exhibited in several locations, writes Kate Siklosi in The Puritan. Siklosi adds that the only passing reference to Philip and the massacre on the Zong was in a “visitor’s guide to the museum where the installation was being held”.

Revelations and questions

Jayawardane: When asked about his use of Williams’s work, Thomas argued for his right to use the news photographs to pose questions. “This is an image that was taken almost 30 years ago that has been distributed and printed hundreds of thousands of times all over the world. At what point can someone else begin to wrestle with these images and issues in a different way… much the way that people would quote from a book?” he asked, in artnet News.

But Thomas’s explanations for what those question she wishes to explore, pose or articulate remain a little muddy. What do audiences need to question or explore about news photography or the image repertoire? How do Thomas’s works achieve that, or communicate those issues, with the changes he made,to be seen under specialised lighting, etcetera?

Thomas, who is known as both a photographer and a brilliant conceptual artist, has been working with archival images for some years. His recent works use bricolages of texts and news photographs — the image and narrative repertoires that make up the zeitgeist of a community during a particular time. In a recent exhibition at the Delaware Art Museum, he included text from the Black Survival Guide, or How to Live through A Police Riot, a pamphlet “circulated by a neighbourhood group in Wilmington in 1968” when the National Guard occupied a black neighbourhood for months after the then governor declared a state of emergency in response to unrest following the assassination of Martin Luther King. He then layered the text with news images and private photos taken during the occupation, and composite images were screen-printed on a reflective material: the reflective “paint” used in road signs.

Documentary photographer Jen Kinney wrote in a review: “To the naked eye, only the pamphlet pages and a ghostly trace of the photographs are visible. When visitors shine a light directly on the images — you can use your phone, or the museum provides special glasses with little flashlights mounted on the sides — photographs of protesters and troops and firefighters emerge, dazzlingly bright. It’s a disorienting experience, like walking through a cloud of smoke.”

Thomas notes that he was fascinated with “the experience in the dark room, where an image sort of appears before your eyes” and hopes that his work allows “viewers of the images and the text [to experience] a revelation, a visual revelation”.

But however sophisticated Thomas’s work may be, some of the explanations and analogies he offered about the works shown at the Goodman did not sit well with South African audiences. This is partly because of the realities of the socio-political landscape, which Thomas may not have read well. He may not have expressed himself well either, because of the fraught situation created by the interview.

But another reason his points may not have sounded strong is because of the inherent nature of constructing arguments and providing evidence. As one of my uncles reminds me, “to argue through analogy is usually one of weakest forms of argumentation”.

Marinovich: On the news show Tonight with Jane Dutton (which aired on 21 September), Hank Willis Thomas says he hoped to raise questions about photography with his work. Thomas notes that his work questions Williams’s and other photographers’ right to photograph public spaces, use the image, and profit from sales — in perpetuity — without the express permission of the folk who are being photographed. Yet Thomas’s original contention is that he should equally be allowed to use that image and any image, without reference or permission from the author or the subjects in the image. This seems like a contradiction.

Thomas then contextualises the debate about appropriation. He points out: “The moral question should always go over a legal question. The moral question is ambiguous, and that is why I apologise if my use of the image was aggravating or disrespectful to him…Any way I can… correct that side of it. However… being an African-American and [having experienced] segregation, we know that sometimes the laws are wrong and they need to be challenged when it comes to context, and I think my work is really trying to ask these questions about the landscape of visual ownership… and both myself and other photographers have gone places, into townships, taken photographs of people’s children, taken photographs of people who do not have the power to circulate and make money out of their images and actually done that very thing, and my work is partially that very thing, and how do we address that very thing… and part of the question that arises out of this is the perennial question of the 21st century, is how do these 20th-century problems get revisited?

“I’m not saying that I am sure that I am always doing it correctly, and this is a learning opportunity for me, and that is where we should be thinking about not just the author, but [that] every person is always important.”

These statements somehow lead, after a question from a viewer about sampling in the music industry, to Thomas hinting at, or more accurately, half articulating and suggesting that there are resonances between his use of Williams’s photograph and “land expropriation”. An argument could be made, he says, that as an African-American, he is “taking back” the land appropriated by Williams, who is a white South African. That argument is utterly moot when the appropriated work is that of African photographers such as Kumalo, Magubane, etcetera.

Thomas states:“…this debate for me is somewhat similar to the land expropriation conversation… The question is… who has entitlement to the land, and what to do with it if we are trying to modify or correct… what we feel were things that were done wrong. In this case…I might be seen as the colonialist… I am the perpetrator… I think it’s complex in such a way that Graeme’s image [is] a claim of an image of someone else…so, like someone who’s claiming the land; and I have reclaimed it. The question is where does it belong?”

The discussion ends with the South African photographer’s request that the work be withdrawn and the American artist glumly agreeing to “whatever he says”.

That final concession seems to be due to Thomas’s own admission that he probably failed to alter the original work sufficiently and had, instead, fallen foul of the (1886) Berne Convention rules on copyright. The legal and financial ramifications, if any, due to Thomas’s reuse of William’s photograph in his artwork will play out over time. But it seems odd that an experienced artist who is represented by two powerful galleries — Jack Shainman Gallery in New York and the Goodman in South Africa — would not have had legal advisers looking into whether his use of historical images would be problematic.

Marinovich: Thomas’s partially enunciated argument about the moral right of Williams to take that photograph of black children in Thokoza can be read as a moral judgement — one made by an African-American artist, about the day-to-day conduct of a white photojournalist who, in his own words, took photographs of what he believed he had a moral imperative to show to the world about the brutal effects of apartheid. On the face of it, it lends itself to an easy judgement in the mind of the progressive and elite market towards which Thomas’s work is aimed. The optics, as they say, are that a young black man is striking a blow against the exploitation of township kids by reusing an image by an older white South African photographer without permission or redress. Those children — we know — were brutalised by the white state, made manifest by the huge armoured vehicle of war and its uniformed guardians. Yet Thomas, by implication and by a deliberate visual excision of the policemen (mostly white) tells us very pointedly how to read the image, and the situation.

The original unreworked image was not politically subtle either, but it did allow us to regard both groups in a more nuanced way, and certainly let us absorb both of these human elements for ourselves.

Marinovich: I have had lots of my work reused in artworks, in plays, music videos, in movies, documentaries and also referenced less directly in other people’s photographs. Sometimes they ask and sometimes they don’t. I almost always give permission, unless their reuse wildly offends me. I do appreciate them asking, and if it is a commercial venture, I ask for some form of payment. Other people just steal it, and I usually send a curt letter with an invoice when it is brought to my attention. I mostly let nongovernmental organisations and the like use my Marikana work for free, or [for] a nominal sum — it seems like the right thing to do, but they do have to ask.

Thomas’s analogies

Jayawardane: In the music industry, today, there are clear laws and guidelines for sampling. Not surprisingly, it boils down to money. That is largely because, in the popular music industry, artists and performers make mega millions for the corporations that support them, and corporations tightly control what they see as their profitable properties. But in Chris McGreal’s article in The Guardian, Thomas references sampling in hip-hop and rap music as an analogy to what he did with Williams’s photograph, saying that his work is“more akin to sampling, remixing, which is also an area that a lot of people said for a long time that rap music wasn’t music because it [was] sampled”. But this analogy seems disingenuous. Those who were around at the time (and historians and other scholars) remember that sampling in hip-hop culture began with culturally marginalised and poor communities in the Bronx during the 1970s and 1980s, who used discarded LPs and 45s to make something new.

Thomas is an African-American who grew up in New York City in the 1980s. Many wondered how he could have missed the history lesson in his own backyard. In any case, I don’t believe that his artistic sampling can be equated with that of marginalised artists who innovated music with discarded materials. Thomas’s formal education includes a BA in photography and Africana studies, an MA in visual criticism, an MFA in the visual arts in photography, a couple of honorary doctorates and a slew of well-deserved, prestigious awards. This education, as well as the socio-political conversations in which he engages, should have grounded him in the ethics and laws of referencing and “remixing”.

Jayawardane: The common thread behind each of the instances of “appropriation” we spoke about is that the original photographer’s or artist’s intellectual and creative labour is erased by the powerful subjectivity of the star artists, performers, and the galleries and lawyers that represent their interests. Fine art, though its practitioners count themselves to be far loftier than those in the world of fashion, seem to practice lifting of intellectual and creative property no differently, and probably for similar reasons. The enormous pressure on stars to produce an evermore innovative assembly line of works for their galleries, group exhibitions, art fairs and biennales seems to create the conditions for such problematic practices; they are questionable at best,exploitative and arrogant at worst, and often deeply wounding to the lesser-known artists from whose bodies of work the famous and powerful take a pinch and a pound.

We may each have quite different positions about how to go about working with an “original” photograph, and how to work with the photographer — living or dead. It is imperative that we have conversations about what makes an artwork an innovative comment that incorporates another artist’s or photographer’s intellectual and creative property, or rather, an unethical appropriation of an arresting image or object made by someone else. It is important to recognise that we cannot really talk about free-flowing ideas without a discussion about power and power relationships.

Even when artists might be able to cover themselves legally, if their appropriated works create painful eruptions and responses that are centred on memories of historical theft and appropriation of cultural materials and objects, we must ask whether their work achieves its goals or creates further wounding.

Ultimately, our goal is to find better — and more equitable — ways of working with each other as artists, writers and creative people who are interested in issues of justice in our communities.