(John McCann & M&G data desk)

Another petrol hike is not what South Africa’s precarious middle class needs. The National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS) will release a report in November on the tendency of citizens to fall into poverty. But the NIDS numbers analysed by the Mail & Guardian are scary.

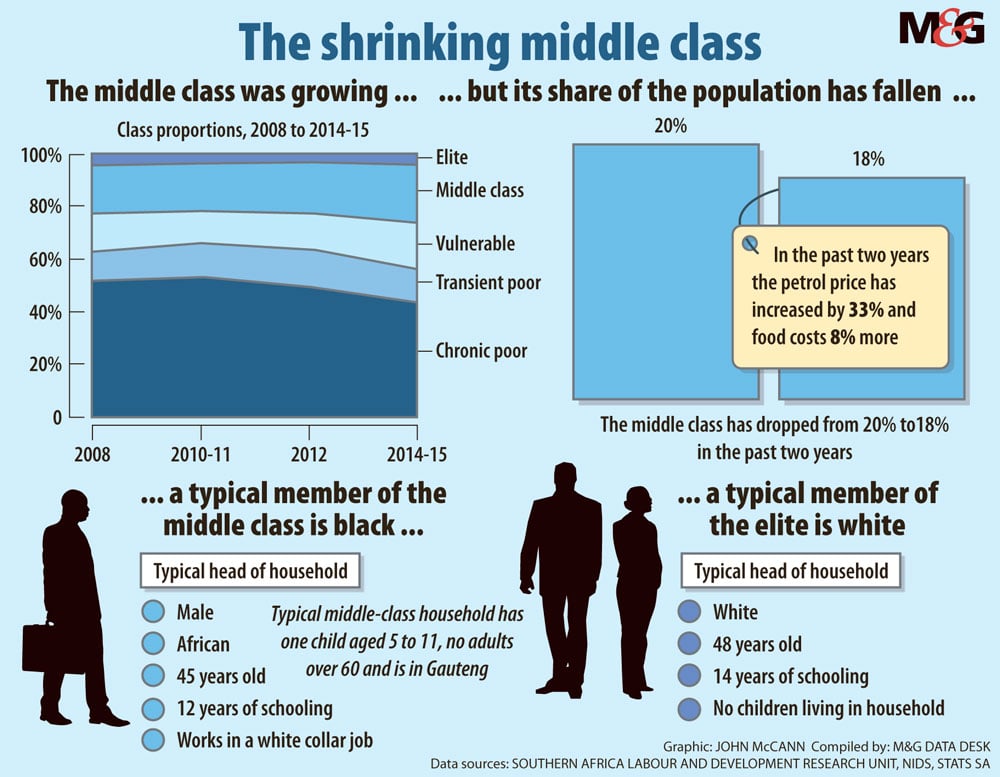

The data shows that, in the past two years, the middle class has shrunk from 20% to 18%. Since September 2016, the cost of petrol has increased by 33% and the cost of food by 8%. The number of “chronically poor” — for whom poverty is a permanent state — has increased and is now more than half of South Africa’s population.

Rocco Zizzamia, a researcher at the University of Cape Town, says poverty affects far more people than the 55% Statistics South Africa counts as poor.

“Poverty is a dynamic phenomenon, with people moving in and out of it all of the time. Many of the 45% of the non-poor fall into poverty over time. While we think of the middle class as a group that faces a lower probability of falling into poverty, the portion that’s in that position of economic stability is surprisingly small,” he says.

The NIDS data is collated using a panel approach, allowing for the research to track people over a period of time. The study collected its first round of data, which is done every two years, in 2008 from a sample of about 28 000. The latest round of data was collected in 2017.

Based on the study’s 2015 outcomes, the middle class was defined as earning between R3 104 and R10 387 a month.

In April, the World Bank released its economic report on the state of South Africa, which found that it is an extremely unequal society and that the current state of the economy is entrenching it even more.

Professor Jannie Rossouw, the head of the University of the Witwatersrand’s school of economics and business sciences, says the decline in the middle class is a result of financial pressures, including poor economic growth, job loses and constant price increases, including that of petrol.

“The middle class is under serious threat at the moment, because the fiscal position of the government is very precarious and South Africa is heading for a fiscal cliff,” he says. “But if you are working in the civil service your middle-class existence is going to be okay, because civil servants get above-inflation increases. If you are employed outside of the civil service, your position is not that guaranteed.”

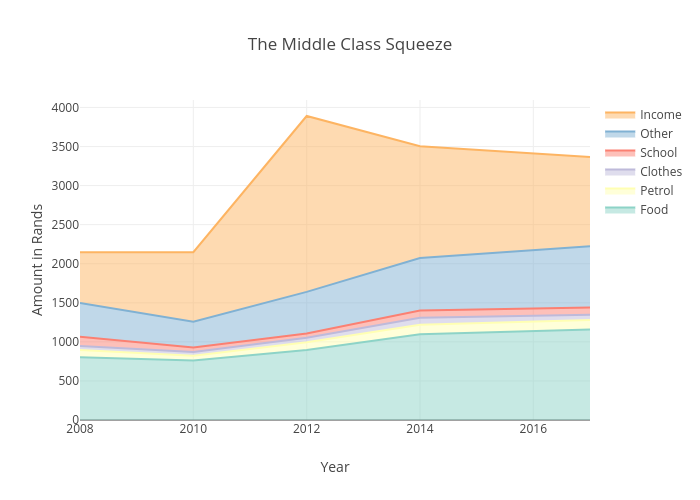

Rossouw adds that the middle class is typically one pay cheque away from poverty. One family from the Northern Cape surveyed by the NIDS is a classic example. In 2008, the family had a total monthly income of R3 600, with R60 a month spent on cellphone services and R20 on gambling.

The main sources of income came from two adults, who are both full-time employees in the clerical support and elementary sectors, which includes manufacturing and wholesale and retail trade. Two other adults are students. Petrol and transport costs were R800 10 years ago and the household’s total expenditure was R2 080.

Last year, the family’s income had dropped to R3 280 in real terms and their expenses had grown to R3 000. One adult is still studying but the other had to drop out as tuition fees have also been on the rise.

Another family from Mpumalanga had an income of R4 000 a month in 2008 but, after one of the breadwinners lost a job, the household’s income in 2017 decreased to R1 880, which, according to NIDS data, puts them on the brink of poverty.

Zizzamia says those who are in the middle class are not always safe and can easily fall into the poor group. Their vulnerability is related to personal shocks, such as losing a child or a job. “Eighteen percent of the population is occupying a position where they are free from only thinking about meeting their basic needs.

He adds: “Remember that the middle-class group is the consumer class that is supposed to be driving and contributing to the economic growth.

“Another way in which people’s vulnerability is affected is through larger economy-wide shocks. Something like a petrol price increase will lead to a general increase to the vulnerability of the middle class. Its effects might not be intensive but extensive — it will affect a large part of the population and chip away at the things that ensure the class has a degree of economic security,” he adds.

Justin Visagie, a research specialist at the Human Sciences Research Council, says another middle-class concern is the issue of inclusive development to keep the vulnerable out of the poverty group.

“Even if someone is lifted out of poverty, if they are not being developed and their productive capability as people isn’t being invested in the economy, we are not being inclusive. The South African economy has to change structurally,” he says.

Visagie says that, if the middle class is being adversely affected, the poor are worse off. “The middle class is being squeezed. It’s a general indicator of a deeper economic malaise that is happening in our country that is very problematic,” he says.

“Where South Africa is at the moment is that we really lack significant economic impetus and it’s affecting everyone, across all the income brackets.”

To compare your household income with the rest of South Africa, visit mg.co.za/compare