(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

Banks are reporting an uptick in the number of new savings accounts but, although some customers might be saving, many continue to rely on credit.

The country is in a technical recession as of last month because of poor first- and second-quarter performances, and unemployment has risen. Statistics South Africa has reported that 69 000 jobs in the formal sector were shed in the last quarter.

More South Africans might be saving in response to the tougher times but others are spending on credit. Economist Mike Schussler says “people are moving to a different kind of debt”, with consumers asking for smaller loans rather than drawing on mortgages.

Although more consumers are applying for credit, a greater number are being declined. The National Credit Regulator reported this week that the total value of new credit granted increased by 8.25% quarter on quarter, and the number of applications for credit has increased by 5.79% quarter on quarter, and 18.1% year on year, to more than 11-million. This is the highest number of credit applications since the fourth quarter of 2015, says Absa economist Peter Worthington.

But the rejection rate for new credit also increased, from 48.5% in the first quarter this year to 50.1% in the second quarter.

Worthington says this suggests “that lenders tilted towards stronger discrimination in the face of higher demand for credit, which would make sense if some of the credit applications were coming from financially stressed consumers”.

“There is also a slower rate of net credit extension,” he adds, which means “households elected to continue servicing their debts but trim optional consumption spending in response to financial pressures”.

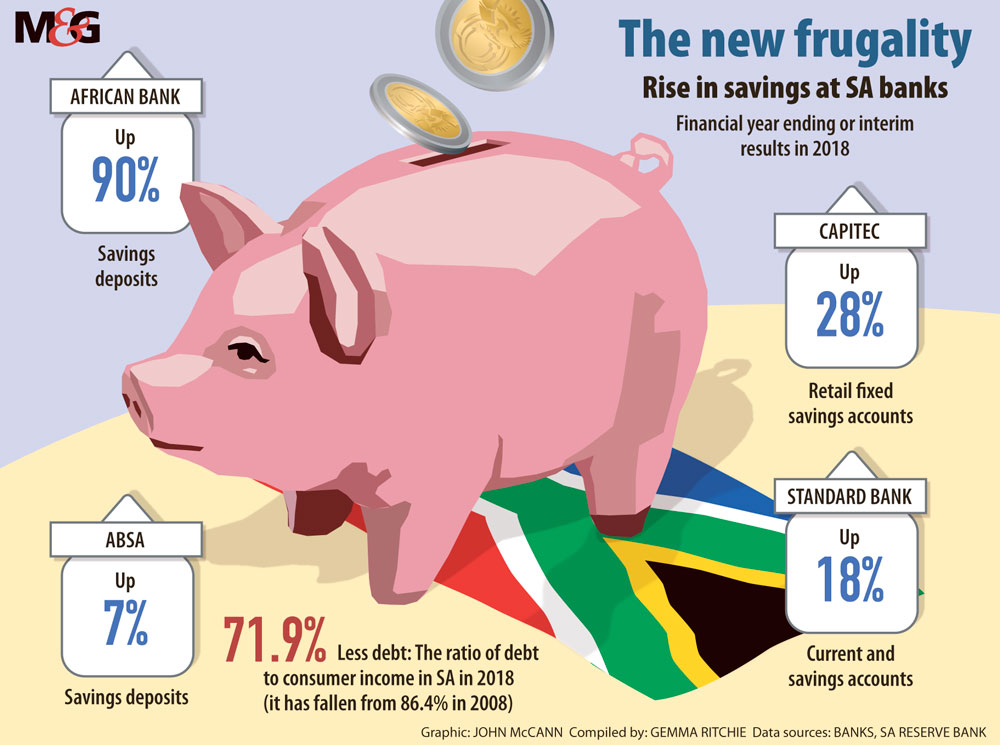

This year, Absa, Capitec, Standard Bank and African Bank have reported that retail deposits are up.

In the past financial year, the value of Capitec has rebounded since a Viceroy report earlier this year, which caused the bank to lose 25% of its value. It has now reported a 28% increase to R23-billion in total retail fixed savings, with retail deposits increasing by 20%. Capitec has attributed this to a “sustained increase in clients’ trust of our brand”. The bank has 9.9-million clients.

African Bank, which collapsed in 2014, reported a 90% increase, to R680-million, in savings deposits as of March this year.

According to the bank’s interim financial results, the number of retail depositors increased from 9 246 to 13 121, and the average deposit increased to R52 000.

Although the bank had the highest percentage increase in clients

opening retail deposits, Standard Bank and Absa reflected moderate growth in their retail deposits and an increase in their loans and advances.

Absa, in its financial results ending June 30, reported an increase in savings deposits by 7% to R189-billion (up from last year’s R177-billion) and an increase of 24% to R3 724-million in gross loans and advances.

At Standard Bank both gross customer loans and deposits have grown at 15%. But it reported a “pleasing balance growth of 18% in current and savings accounts”.

The reason more consumers could be saving, and applying for less credit, could be attributed to consumer wariness.

“We think consumers, despite the apparent surge in Ramaphoria-induced confidence in Q1 and Q2, are simply less willing to borrow to fund optional expenditure, having been traumatised by the debt burdens of the global financial crisis and the splurge of seemingly cheap but actually unaffordable credit in the subsequent unsecured lending boom domestically,” according to Worthington.

Schussler says this week’s results have shown that consumer credit is healthier, and banks and financial institutions are being more conservative about lending.

The ratio of debt to consumer income is 71.9%, according to the South African Reserve Bank, an improvement from 86.4% in 2008.

On average, consumers are spending 14%of their budget on savings, according to the 2018 Old Mutual savings and investment monitor, a decrease from last year’s 15%. The Old Mutual report shows that consumers are spending 67% of their income on living expenses, up from 62% in 2017. Households also spent 3% less on servicing debt this year than they did in the previous financial year.

As of June, 11-million consumers have applied for credit, which is not surprising because many consumers “tend to turn towards credit during tough economic times”, Debt Rescue chief executive Neil Roets says.

“The reality is that the dramatic increases in fuel and the secondary effect on all goods is placing enormous strain on consumers’ finances.”

He says the rising cost of living makes it more difficult for consumers who already have debt to meet the increases and pay off their credit instalments.

In a June report, Debt Rescue says more than half of South Africa’s

consumers are more than three months behind with their repayments. The recent National Credit Regulator results indicate that, at the end of June, the total credit consumers owed was R1.8-trillion, a 1.14% quarter-on-quarter increase and 4.76% up year on year.

Although the regulator reports that the number of credit-active consumers has decreased by 3.44% from 25.46-million to 24.59-million, the number of consumers whose debt is in good standing also decreased.

According to Absa macroeconomists Miyelani Maluleke and Worthington, “consumers have been slow to borrow”.

They add that, according to the Bureau for Economic Research’s second quarter survey for the year, consumers “appear exceptionally optimistic”, and the consumer confidence survey conducted between April 20 and June 7 showed that household confidence in the economy and their financial positions “remained close to the record figures” seen in the first quarter.

“Even though credit may be available generally, at least to the more creditworthy borrowers, it may be coming at a relatively higher price,” they add.

“Consumers do not want to contract debt for optional spending. But they may, during a difficult downturn, such as the current one, be willing to borrow to fund essential spending.”

Using the Reserve Bank’s analysis of Stats SA’s data, Maluleke and Worthington say the data in the second quarter of 2018 shows that “real household disposable income growth slowed to a mere 1.5% year on year”.

But Worthington says the data also shows that “households have been deleveraging [reducing debt by selling off assets] since about 2014, even after the cost of servicing the household debt [relative to disposable income] started to fall in 2016”.

An increased reliance on credit has been touted by financial institutions as one of the reasons South Africans are less likely to save.

The institutions have also said that low levels of financial literacy, a weak saving culture and the growing unemployment rate are hindering banks’ attempts to encourage more people to save.