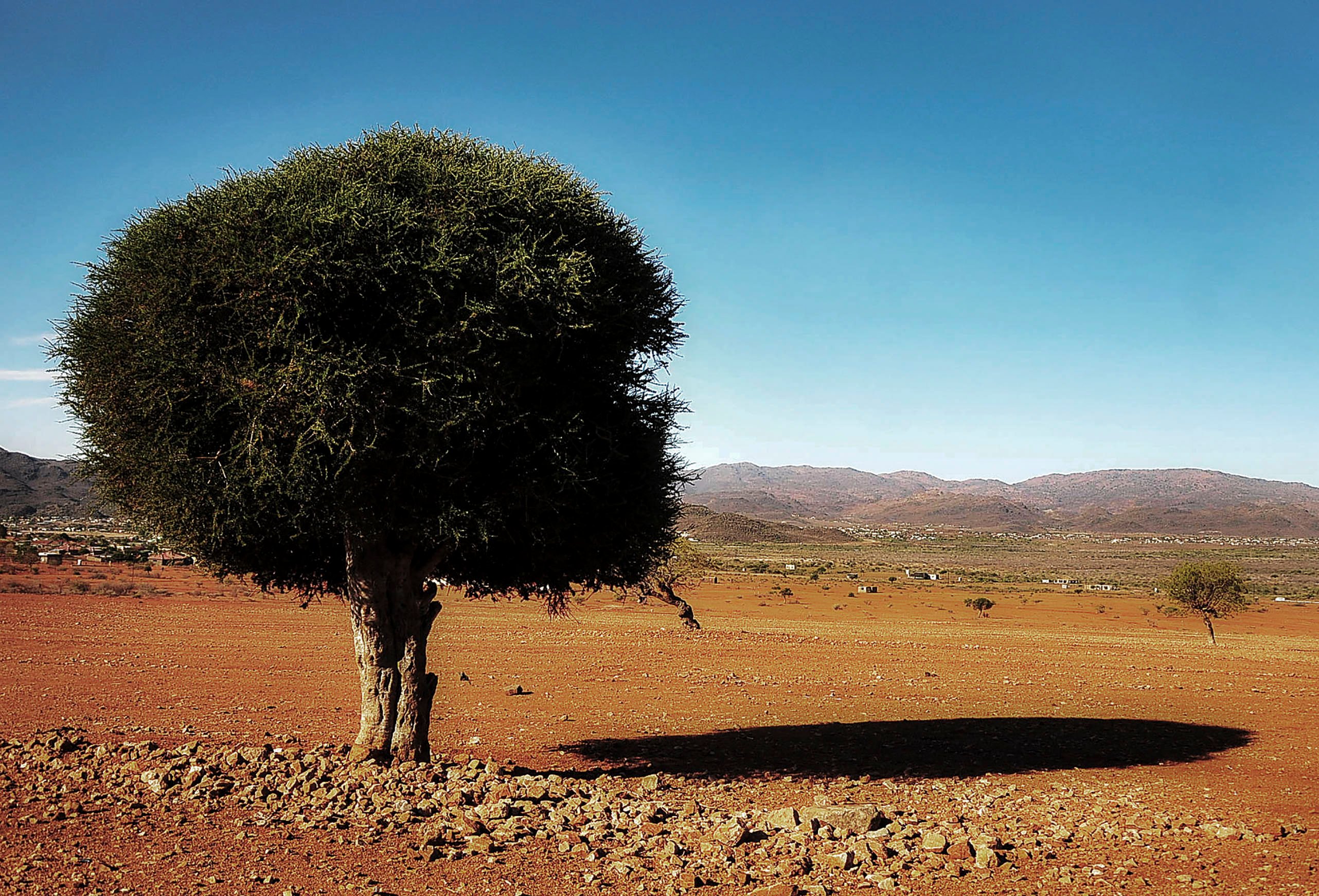

Platinum mining, evident from the trail of dust in the distance, could be a source of income for residents, one which Bapedi royals want to explore from Thulare IIIs seat in Mohlaletse village. (Lucas Ledwaba/Mukurukuru Media)

The absence of Kenneth Kgagudi (KK) Sekhukhune, the deposed acting kgoshikgolo (king) of the Bapedi Marota, from a unity and reconciliation lekgotla has cast doubt on whether the troubled kingdom has seen the last of its decades-long royal feud.

He also did not send a delegation to the meeting called by his nephew and rival, Thulare Victor Thulare (Thulare III). Held this past weekend, it was attended by more than 150 magoshi (chiefs), matona (sub-chiefs) and their representatives.

Kgoshikgolo Thulare Victor Thulare. (Lucas Ledwaba/Mukurukuru Media)

KK’s moshate (palace) is based in Maroteng, a sub-village of Mohlaletse, less than 5km from Thulare III’s moshate, Maebe Tjate (Great Place).

Mohlaletse is the seat of the Bapedi kingship which has been contested since 1986. (Lucas Ledwana/Mukurukuru Media)

Thulare told the gathering he had forgiven “those who caused divisions in the kingdom” and apologised to the royals for the long-raging dispute.

It arose after Thulare’s father, Rhyne Thulare Sekhukhune, and his supporters launched a violent attempt to unseat KK in 1986. KK had been installed as acting kgoshikgolo in 1976 after Rhyne Thulare had refused to ascend the throne without the blessing of his mother Mankopodi, who was acting regent after the death of her husband in 1965. The matter became the subject of many court battles from 1988 into the mid-2000s.

After Rhyne Thulare’s death in 2008, his son Thulare III lodged a claim to the kingship with the Commission on Traditional Leadership and Claims. In 2010, the commission recommended that Thulare III become the Bapedi kgoshikgolo and handed its findings to then-president Jacob Zuma in January that year. Zuma made the announcement public in July 2010.

Last Sunday’s meeting came in the wake of a recent high court decision to refuse KK leave to appeal an earlier judgment endorsing the 2010 finding by the commission to depose him as the acting kgoshikgolo and recognise Thulare III as the kgoshikgolo.

A delegate speaks during a lekgotla called by kgoshikgolo Thulare Victor Thulare to discuss reconciliation, after his latest court victory again declared him the legitimate leader of the Bapedi Marota. KK Sekhukhune, the deposed leader, did not attend. (Lucas Ledwaba/Mukurukuru Media)

There is now speculation that the feud might continue with another court battle. Early this month, the judge president of Gauteng, Dunstan Mlambo, dismissed KK’s appeal saying neither KK nor the Mohlaletsi Traditional Council had a chance of convincing another court to come to a different decision. But KK, whose office could not be reached for comment this week, may petition the Supreme Court of Appeal and the Constitutional Court.

Thulare III attended the weekend meeting flanked by bodyguards armed with automatic machine guns and firearms. In a brief address to the gathering held in two tents on the grounds of his moshate, he said he had enlisted the bodyguards because he still did not trust “certain people”.

Thulare III has set up a task team, comprising members of the royal family, to unite and reconcile his divided kingdom.

One of the team members, kgoshi Setlamorago Thobejane, said his mandate was to bring the 13 houses of the Bapedi kingdom, including KK’s, together. These represent the families of the half-brothers of both KK and Thulare III.

But it appears that the task team has its work cut out for it because only three houses honoured Thulare III’s invitation to the meeting. Their absence has raised suspicion that they may still be loyal to KK.

Asked about this, Thobejane sounded hopeful. “I will go and talk to him [KK] also,” he said.

Thulare royal house spokesperson Kgetjepe Makotanyane said there were an estimated 75 magoshi in the Bapedi Marota, located in Limpopo, Mpumalanga and Gauteng. He said the task team had been mandated to build unity and reconciliation “so that we can move forward”.

Some of the land under the Bapedi Marota includes part of the Bushveld platinum complex in Limpopo. The area in the Sekhukhune District Municipality includes the towns of Burgersfort, Steelpoort, Apel and Atok and boasts more than a dozen mines, which have some of the world’s biggest platinum and chrome group metal reserves.

Thobejane said one of the goals of unifying the nation was to ensure that the Bapedi could present a united front in dealing with the mining companies.

“We [Bapedi] are not solid. We are telling [Bapedi royals] that, when our grandfathers left us, they gave us a mandate to say [we must] look after the Bapedi nation. We have got a responsibility. Why are we [now] taking our own route abandoning the mandate all of us were given and looking at self-interest?” Thobejane said.

He added that, although the mining companies were operating on farms bought by the Bapedi, there was little to show in terms of material benefits for the kingdom’s people, many of whom were unemployed and relied on government social grants and remittances from migrant labourers.

The high court judgment has given the Bapedi hope they can recover land lost after King Sekhukhune I was defeated by a combined force of British, Boer and Swazi regiments in December 1879.

Although Sekhukhune I, who resisted British and Voortrekker attempts to unseat him for more than a decade, claimed his kingdom stretched from the Lekoa (Vaal) to the Lebopo (Limpopo) rivers, the entire area known as Lekwebepe (former Transvaal), this is disputed.

Other nations such as the Venda, Ndebele, Tsonga/Shangaan, Bakgaga and Bakgatla occupied parts of the Transvaal long before Sekhukhune’s reign.

“Now that the court has ruled, all the land must return to us. Sekhukhune [land] goes right up to the Vaal. We will find a way to ensure that we get our land

back. The apartheid government messed up our kingdom. Then the ANC came and divided the Transvaal into different smaller areas [Gauteng, Mpumalanga, North West and Limpopo]. Now, through dialogue, we can get this [land] back. If it doesn’t work, we may have to look to the courts,” said Makotanyane.

The finding against KK also seems to have ignited a renewed longing for Bapedi nationalism. Delegates at the unity meeting expressed a desire to build a kingdom as strong and united as that led by King Goodwill Zwelithini of the amaZulu.

In August, the magoshi petitioned President Cyril Ramaphosa’s office, calling for the conclusion of a process to crown Thulare III as kgoshikgolo. The presidency has acknow-ledged receipt of the petition.

The magoshi cited the April judgment as one of the reasons for their demands.

In the petition, the magoshi also laid bare the practical difficulties brought about by the battle for the throne.

“Illegal initiation schools and illegal mining have now become common occurrences in our areas as a result of two centres of power, and will be perpetuated by this appeal process,” they said.

“The delay in our kgoshikgolo’s coronation continues to cause divisions and mistrusts among ourselves and communities we represent. With the speed at which KK and his fellow illegitimate traditional leaders are going in disposing of our land and the devastating increase in illegal mining, damage will be too great and irreversible at the conclusion of this appeal process.” — Mukurukuru Media