(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

The treasury has refused to provide additional funding for the public sector salary bill, because the government can no longer afford it.

While tabling his first mid-term budget policy statement, Finance Minister Tito Mboweni said the wage bill was the biggest cost pressure on the state and it had pushed out funding for other goods and services.

The three-year settlement agreed on in June by the government and unions added R30.2-billion to the R212.5-billion the treasury had budgeted for salary increases and other remuneration benefits over the medium-term period. Mboweni said simply: “We have not allocated money for it.”

Instead, provincial and national departments would have to find the money from the R1.8-trillion they receive.

“This means increasing efficiency and carefully managing overtime and performance incentives,” according to the budget document.

Treasury officials say the framework for how departments can achieve this is likely to be announced in the February 2019 budget speech and will be based on the outcome of discussions between the public service and administration department, unions and other departments.

Officials say the decision will affect departments differently. Some will be able to absorb the increase in their wage expenditure limits by not filling posts left vacant by resignations and retirements, but personnel-driven departments will struggle. These include defence, police, provincial health and provincial education, which are already experiencing spending constraints and which, besides natural attrition, will have to consider early retirement and employee-initiated severance packages.

But the treasury has not allocated money for early retirements and the possible cost of this, and whether it will be an option will depend on discussions with the unions.

Also, according to the Jobs Summit framework agreement to tackle unemployment, “there will be no retrenchments in the public sector”.

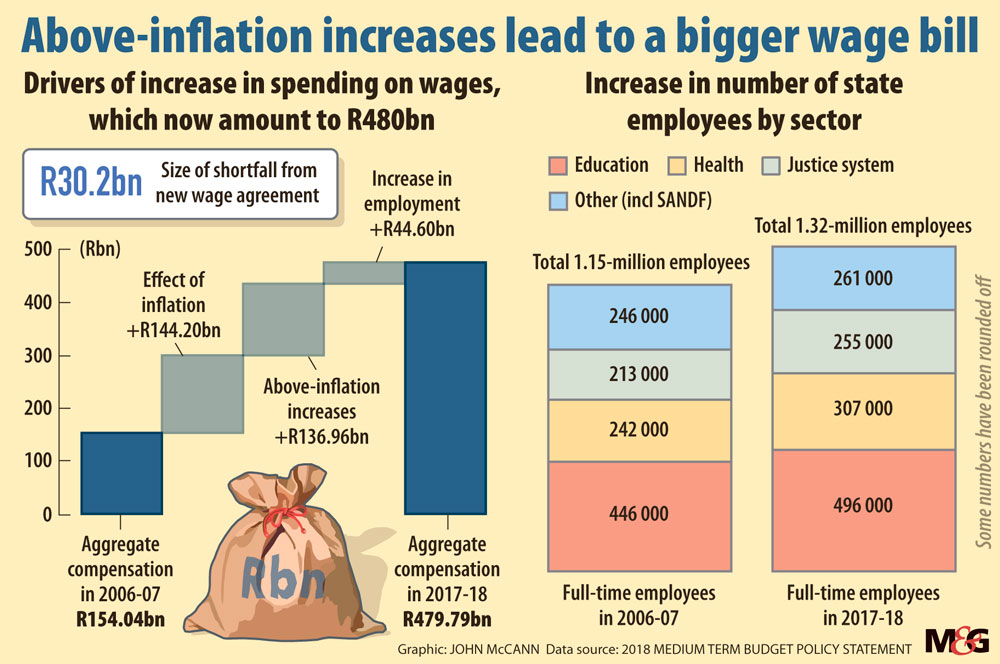

Over the past decade, the salary bill has grown from 32.8% of government spending to 35%. “Around 85% of the increase in the wage bill is due to higher wages, rather than headcount increases,” Mboweni said.

Government expenditure on wages more than tripled since 2006-2007, from R154-billion to R480-billion in 2017-2018. Inflation-linked increases accounted for R144-billion and above-inflation increases added R136.96-billion. Only R44-billion was as a result of an increase in employment.

Speaking to reporters, Mboweni said the government, before beginning negotiations with the unions, would have to lead by example by trimming its own staff complement and spending on benefits.

He said that ideally the Cabinet should consist of no more than 25 ministers. “We have no economically, financially and politically understandable reason that you can have an executive of up to 70.”

Jannie Rossouw, the head at University of the Witwatersrand’s school of economic and business sciences, agreed with Mboweni that the government needed to set an example by reducing its expenditure on public wages to below 30% of overall government spending. “It’s time for President [Cyril] Ramaphosa to show leadership. We need to reduce the size of the Cabinet and with that bureaucratic oversupply.”

A good step would be to get rid of departments — for example, by merging the small business development department with that of trade and industry department. And the economic cluster departments should be merged into one, as well as arts and culture and sports and recreation, he said.

The government also needed to close down or sell off unviable state-owned entities (SOEs), backing Mboweni’s statement that “there should be no holy cows”.

“I fully agree, holy cows make the best hamburger patties — slaughter them,” Rossouw said.

Tahir Maepa, spokesperson for the Public Service Association, said, although the union was aware that this was just a policy statement, it would be watching to see whether Mboweni delivered a “reasonable budget that makes sense” in February.

“There is no way that we are going to sit back and allow a situation where dysfunctional SOEs keep on taking from the fiscus and we take the brunt for it. We are going to take him on,” Maepa said.

Civil servants were “easy prey” because they did not have public sympathy as a result of the poor provision of services, he said. No one addressed the fact that the public service did not have the capacity to deliver appropriate services.

“We have been put to failure and, when we fail, we are being blamed on both sides,” he said.

Matthew Parks, parliamentary co-ordinator for trade union federation Cosatu, said in a statement it was “unfortunate and provocative” for Mboweni to blame workers for the fiscal crisis instead of drawing attention to the effects of corruption and a “bloated” Cabinet.

Mboweni did discuss the size of the Cabinet: “If he [Ramaphosa] asked me about the size of the Cabinet‚ I would say preferably having not more than 25 members. Probably 20 ministers are more than ideal.”

Maepa said the government by its own admission had lost billions of rands to corruption and maladministration and, despite all the talk about clamping down on it over the past five years, there had yet to be an arrest.

“Who are these thieves? The majority of these thieves are his fellow Cabinet ministers and MPs who are sitting with him in Parliament. Why don’t they start dealing with those first?”

Tebogo Tshwane is an Adamela Trust business reporter at the Mail & Guardian