Nobel peace prize laureate Yemeni Tawakkol Karman (right), flanked by Egyptian opposition politician Ayman Nour (left), holds pictures of Jamal Khashoggi during a demonstration in front of the Saudi Arabian consulate in Istanbul. (Ozan Kose/AFP)

MEDIA FREEDOM

Until last Saturday, I was hopeful that the disappearance of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggiat his country’s consulate in Istanbul was no more than a case of censure that would result in his transfer home to face trial or in silencing him. But revelations on Saturday night and Sunday strongly suggest that he has been assassinated.

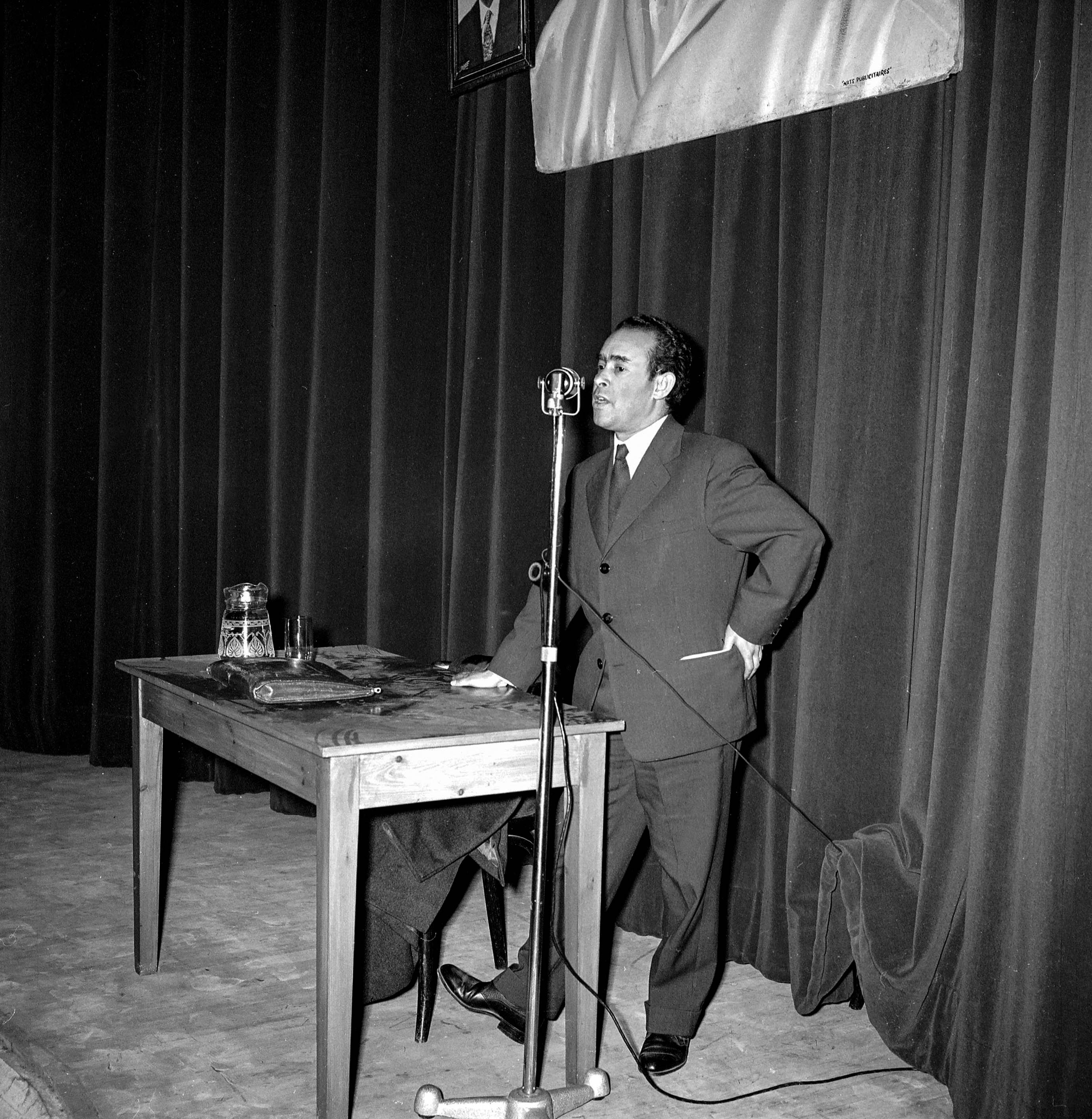

This would turn his vanishing into a rerun of the disappearance of left-wing Moroccan politician Mehdi Ben Barka in 1965, coincidentally in the same month as that of Khashoggi.

Ben Barka’s disappearance and presumed murder in Paris became a heavy burden on the Moroccan regime and jeopardised any prospect of normalisation of relations with the opposition. Similarly, the Khashoggi case could become a burden too heavy for Saudi Arabia to bear.

Jamal Khashoggi’s ‘disappearance’ in Istanbul could be even more troubling for Saudi Arabia than Moroccan opposition leader Mehdi Ben Barka’s ‘disappearance’ in Paris in 1965. (AFP)

Nothing is certain, but should Khashoggi’s assassination be confirmed, Saudi Arabia and the Middle East region will take a dangerous turn. Such a development will have implications for Saudi Arabia’s relations with Turkey. It could also scupper the idea of a “Sunni Nato” revived by United States President Donald Trump. And it could adversely affect Saudi relations with the West — including the US, particularly after Trump’s recent pronouncements on bilateral relations, in which he said Saudi Arabia wouldn’t last two weeks without US support: “I said, ‘King, we’re protecting you. You might not be there for two weeks without us. You have to pay for your military’.”

The West cannot remain silent and prioritise its interests over its values if Khashoggi is found to have been murdered.

I met Khashoggi in May at a conference on security and political arrangements for the Middle East and North Africa. The gathering brought together a galaxy of intellectuals and pundits from the Arab and Islamic world. Khashoggi was a keynote speaker in the closing session.

He provided a sensible assessment of the situation across the Arab world, from countries that embraced change and defended it inside and outside the Arab world to those that are openly opposed to change or that ask to be left alone after they faced adversity and saw their nations torn apart.

The kernel of his presentation was his defence of the strategic interests of Saudi Arabia and what he regarded as the risks that Iran’s alleged nuclear programme and expansionist designs pose to the region. The International Court of Justice ordered the US to lift restrictions on humanitarian trade, food, medicine and civil aviation after it reimposed sanctions on Iran, The Guardian reported.

It was no secret that Khashoggi was opposed to Saudi Arabia’s new policies, or, rather, new developments in his country had led him to keep his distance from decision-makers after having been a defender of his country and its policies and institutions.

The new policies and new methods for conducting public affairs in Saudi Arabia had forced him into self-exile and into a liberal opposition to the situation in his country. He was not loath to air his views, whether on television channels, at forums, in meetings or in the columns of The Washington Post, which were characterised by depth and audacity. I was a regular reader of his articles, which helped me to understand what was happening in the Saudi kingdom.

Khashoggi wanted to prevent liberal and reformist movements from being left to the mercy of authoritarian regimes by encouraging them to align with the dynamics of their societies. To put it differently, he wanted to have them recognise Islamic views regardless of their differences, because they are a reflection of a societal reality and an internal dynamic. Turning them into an enemy might hamper their evolution, drive them into withdrawal and, eventually, extremism.

It was a principled position, which he articulated without neglecting the core principles underpinning modernist thought, including the emancipation of women, the introduction of legal standards for political action, balance among branches of government and democracy.

This vision is bothersome for regimes that unilaterally decide the fate of adversaries and dissidents by pitting one movement against the other. It is also troublesome for regimes focused on dealing with the present to the detriment of their own strategic interests; regimes that refuse to abide by standards or account for their actions.

Particularly striking was Khashoggi’s defence of his country’s strategic interests. Some dissidents confuse views, persons and regimes with the strategic interests of their countries, losing their credibility in the process. Khashoggi did not fall in this category. He stood for something new that observers of Saudi Arabia’s affairs tend to overlook: liberal views that wish to be immersed in global trends and universal experience.

His disappearance signals a dramatic shift in the West’s perception of Saudi Arabia. But it will not kill his ideas. On the contrary, they become more dangerous. Khashoggi is now an idea that poses a greater danger to the establishment in Saudi Arabia than he did when he was still alive.

The disappearance of a person whose sole weapon was his pen brings to mind an incident that changed the course of the Middle East, when the henchmen of the Ottoman caliph — then the embodiment of Islamic unity — executed Arab nationalists in May 1916 in Damascus.

When Emir Faisal bin Hussein, a leader of the Arab revolt against the Ottomans and later king of the Arab kingdom of Syria, heard the news, he sprang to his feet in a fit of rage and shouted that a line marked a break with a system that was hitherto seen as the custodian of Islam: “Death has never been so appealing, oh Arabs!”

The smallest spark can often ignite the largest fire.

Hassan Aourid is a former spokesperson of the Moroccan royal palace and a lecturer in political science at Muhammad the Fifth University in Rabat