Tongues: A photo in the 'Daughter of District Six' exhibition is of Gayle, the language used initially by gay people. Photo: David Harrison

Gaseroen Samuels laughs as he recalls the years of fun he had in Cape Town’s District Six with his large, all-queer posse. “Oooh jinne man, those were the good days. You know, in summer, when we would come from a party or something, we would take a mattress out on to the pavement and sleep there. Then, when people are going to church in the morning, we would be sitting there on that mattress with coffee and koeksisters. Dan skinner ons lekker van die mense [Then we had a lovely gossip about the people].”

Their languages of choice for said gossip sessions were English and Afrikaans. And thrown into the mix was Gayle, the then predominantly queer language made up largely of women’s names. Gertie is girl. Cindy is child. Harriet is hair. Lana is dick. Hazel is butt.

And, as any Gayle speaker would tell you, speaking it would, more often than not, result in uproarious laughter.

“We would say things like ‘Kyk hoe Olive lyk sy’ [look how cute she is] or ‘Nancy, die bag is vast Olga [No, the man is very old].”

Now 79 years old, Samuels — “everybody calls me Sammy or Samantha” — adds that he is “still from the old days. The young ones use the new words, but we don’t understand the new words.”

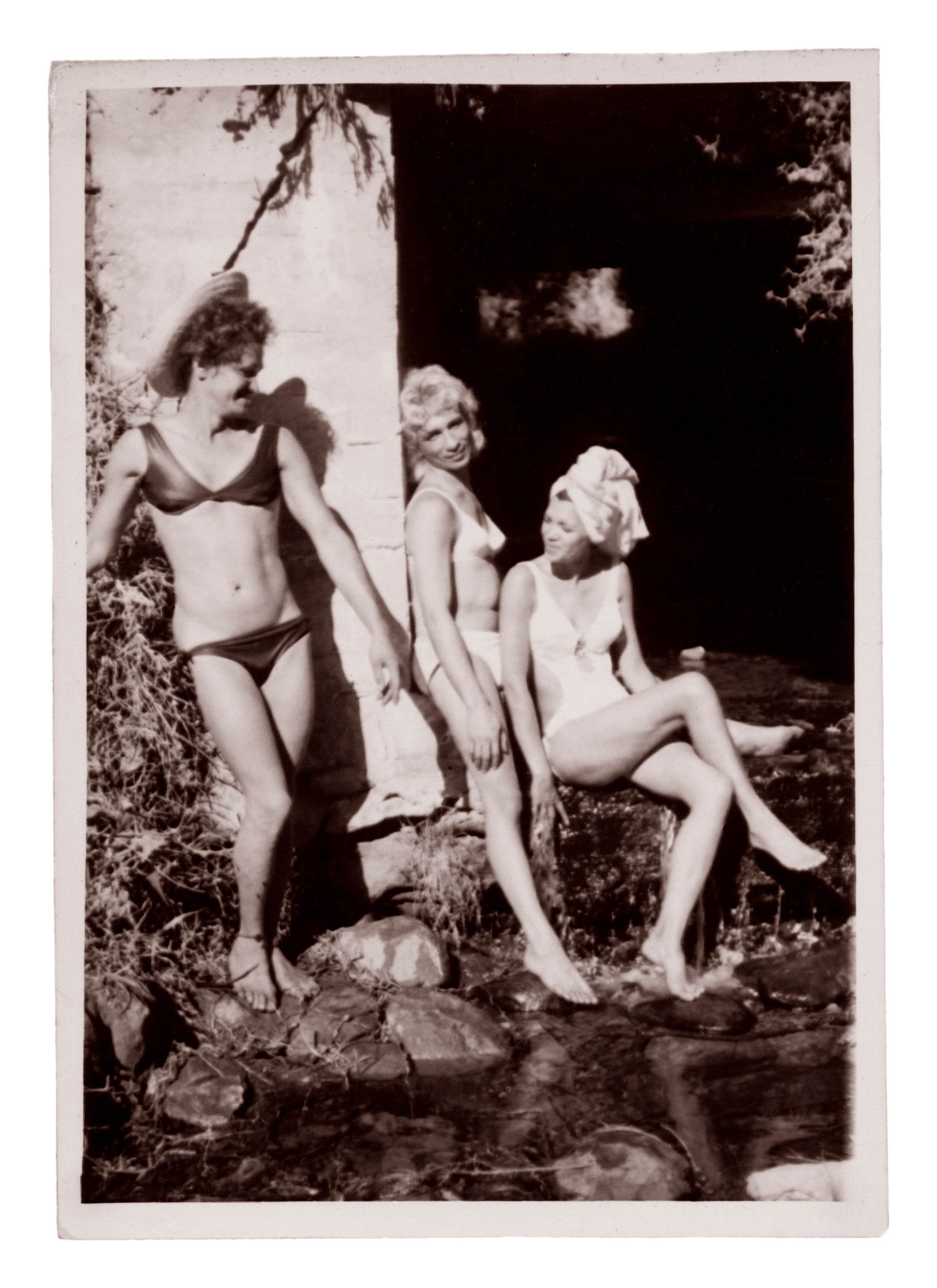

Circa 1971: Sammy aka Gaseroen Samuels (left) poses with other District Six friends, Kewpie (centre) and Liz.

Still a hugely popular language, Gayle has transformed not only in terms of the words used, but also regarding who speaks it. Initially spoken predominantly among queer men and women, its reach is now much broader.

This is what filmmaker Lauren Mulligan aims to show with her 16-minute documentary, Visiting Gayle, currently on show at Cape Town’s South African National Gallery as part of the gallery’s Not the Usual Suspects exhibition.

Eschewing the traditional documentary style, Mulligan instead takes a more intimate approach, following a group of her close friends as they use the language in their everyday lives. Queer boys, girls and straight folk Lulu (laugh) and Gail (speak) in, well, Gayle — often to hilarious effect.

‘Visiting Gayle’: Lauren Muligan’s documentary looks into Gayle and how it continues to be used today. Photo: Delwyn Verasamy

“I did not want to put in a historical account,” says Mulligan, who completed the film as part of her master’s degree at the University of the Witwatersrand’s film and television department. I just wanted to show it in conversation. To show that conversations [in Gayle] aren’t linear and that is why I structured the film that way. It isn’t this kind of conventional documentary.”

Although she grew up with the language spoken around her, Mulligan says her curiosity in exploring it through film was piqued when she asked her brother and his friends — regular Gaylers — where it came from.

“One person said it may have come from the prisons, like a prison language. But nobody actually knew. What everybody agreed on was that it started in District Six. But some would say it started in the Sixties, others say in the Seventies. Nobody seems to know, though.”

But Sammy knows. It was his all-queer posse that created the language, he says. “We were a big clan together. It was me, Kewpie, Olivia, Patsy, Miss World, Sue. There were even more. All of them are dead now. Piper is also dead. But Miss Caron is still alive,” he says, adding: “When we came together, we started Gayle.”

It began at Invery Place, a block of flats in Woodstock they dubbed “Queens Hotel”, because “al die queens was daar … Weekends it was like a madhouse.”

But it was really in the petri dish of hair salons that the language took off. “We took Gayle to our salons and nobody knew anything about it, because it was also new to them. En ons het so lekker gekekkel van die customers and they didn’t even know that we were gossiping about them. We would say ‘Harriet or Barbara this’ or ‘Ursula that’, you know, so they just thought we were talking about women we knew.”

Sammy adds that, although he enjoyed being able to discuss people freely with them being none the wiser, he did teach his boyfriends — whom he described as “really good men, but ooh their wives were full of shit”.

“When we first started it, I taught my partner at the time and he just laughed himself sick. He would say, ‘Where do you come on these words?’ But we did it to gossip about people, so that they don’t understand what you are talking about, you understand? People would ask us, ‘Van wat praat julle nou? [What are you talking about?]’ But we would just leave it, because as hulle die Gayle ken, dan kan hulle ook skinner [if they understood, they would also be able to gossip like us]”.

Offering up some examples, Sammy says: “We would maybe say, ‘Die bag wil nou weer gaan Nita’. [This guy wants to fuck again]. Then someone would maybe reply, ‘Nancy, hy’t ’n hoender nekkie … Ek soek ’n vast Lana [No, he has a small dick. I want a big cock]”.

But the language also came in handy for another reason: safety. “If we felt scared or threatened, we could say something like, ‘Ek is vast Barbara (I am very scared.)”

Mulligan agrees. “What I found interesting was that most of the literature placed Gayle with men. But it wasn’t that. With coloured users specifically, men and women were using it. One of my participants said they used Gayle as a way to keep each other safe. Like when they went to nightclubs or spaces that were more straight, they’d be able to protect each other using Gayle. Like, ‘Nancy vir die bag. Hy’s Reva’ [No for that guy. He’s rough]. Women would, for example, be able to say, ‘You are in a bit of danger here as a gay man’. Or gay men could say, ‘You are in a bit of danger here as a woman’.”

Although little research has been conducted into Gayle, the research there is, says Mulligan, “was positioned in the wrong place”. Here she is referring specifically to Ken Cage’s 1999 thesis focusing on the language and his 2003 Gayle dictionary.

“People would say, ‘Oh, but there is a dictionary on Gayle’, but what they didn’t realise was that they were not in that literature.

“I’m not saying it was an intentional thing,” she says of Cage’s research being made up of interviews only with white men, “but I had to question this act of erasure that happened.”

Cage acknowledges that his research “was initially intended to research Gayle across all gender and racial barriers”, but there had been a “lack of access to gay people of colour and gay females”.

“Look, I am not trying to negate what Cage has done,” says Mulligan. “But what I’m saying is that I didn’t see myself and the community that I know in that literature.”

Mulligan hopes her film will spark research interest in the language from linguists “because then we could get more clues into who uses it and why. Previous research, for example, says that Gayle was used to navigate spaces and hide your sexual orientation. And that is fine, especially under a very oppressive regime like apartheid. But then why does Gayle still live on today? You see, it’s just not that simple.”

As to why she thinks it continues to be spoken to this day, Mulligan says: “Gayle lives on because it is performative. And because people enjoy playing with language. It is colourful, it is playful, it is creative. And it’s actually really, really fun.”

l Not the Usual Suspects runs at the South African National Gallery until April 21.

Carl Collison is the Other Foundation’s Rainbow Fellow at the Mail & Guardian