Music educator Nandipha Mnyani looks through the Samro Foundation archives in her search for renowned indigenous tunes. (Manyatsa Monyamane/M&G)

Umagunqelindawo, a song in which a bride sings about her dissatisfaction with her marital home, is a tune that falls in the tradition of wedding songs, even if it deals with how difficult life can be for young, newly married women. Sung in various parts of the Eastern Cape, each region arranges it in their own unique way.

“Arrangements depended on the mood of the singer,” says Nandipha Mnyani, a music educator working at the South African Music Rights Organisation (Samro) Foundation on an archiving and notation project called the Indigenous African Music Archive Digitisation Project. “Different arrangements could be liberating in different ways.”

When I first meet Mnyani she seems a nervous interviewee, but her mind is on her upcoming meeting with her master’s degree supervisor. Our follow-up conversations are less strained; she’s eager to impart the knowledge gleaned from her field research.

Mnyani speculates that Umagunqelindawo could possibly be a song about the fraught nature of ukukotiza, as it features lines such as “Emzini kushushu, emzini kubuhlungu (The bridal home is hot, the bridal home is painful)”. A song of pain and alienation, Mnyani says that, in many African traditions, it was rare to find a lone person performing a song, because music performed a communal function.

“Even if they were alone in the singing, performing the music to an audience, if they were playing uhadi, for example, the performer would ask the audience to clap.”

Mnyani says indigenous music was generally not for entertainment purposes, though the setting and the act of singing communally could engender feelings of being entertained. “The most important thing is the message being passed on, the education you get from the music. You would be told how ceremonies are done through the music. Umakoti was told how to behave or run through her chores through songs for the new bride. The process yokuyala [instructions for how to conduct one’s self in this new stage] was communicated through song too.”

The context people found themselves in and their social standing often dictated the subject

matter of the music. “Sotho men have an instrument called lesiba, which they would play when they were looking after livestock in the field. Most of the songs they would sing then would be about birds, rodents and the environment around them.

“NgesiXhosa, around initiation, iingoma zomtshotsho would serve to pass a message to the village ‘that my time has come to be a man.’ The messages in lullabies, for example, are believed to stay in the subconscious mind, which is why some people say that African children learn music from their mothers [even before they are born].”

Mnyani is fascinated by multilingual songs, which reveal their travels through different stages of colonialism. “The song Makoti ke Dinako is a song telling the bride that it is time to go, with the family making sure that she is happy to be left there [at her bridal home],” she says. “The fact that it is multilingual shows the true beauty of South Africa, its different languages. It is great to hear them mixed together. So it is not strictly a Setswana song, because it has phrases like ‘wajikajika’.”

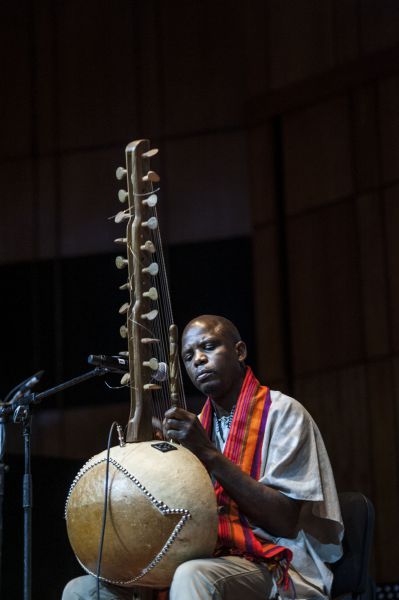

Mmangwane Mpulele is a wedding song that has many different versions, in as many languages as are spoken in South Africa. “Judith Sephuma has her own version, as does Joe Makhanza, a South African kora player known for his versions of popular songs.”

Joe Makhanza is famous for creating his own instruments and versions of local standards such as the wedding song Mmangwane Mpulele. (Manyatsa Monyamane/M&G)

Mnyani did her honours project on Xhosa wedding songs, studying their meanings in relation to their contexts. [She is doing her master’s on cultural preservation in education.] A relative introduced her to the women of eNgcobo, where they gathered not only to sing for her, but also to explain the context of several practices such as polygamy. “This song Umagunqelindawo has a famous arrangement done by Nofinishi Dywili,” says Mnyani.

This is probably because it was among the tunes recorded by ethnomusicologist Hugh Tracey that now reside at Rhodes University’s International Library of African Music.

The Samro project, funded by the US Ambassador’s Fund for Cultural Preservation to the tune of $88 179, involves transcribing indigenous songs into notation so that they may live on, not only for future generations of South Africans, but also for the global community of musicians. The selection process, which may involve up to 50 songs, is governed by a committee, which includes the likes of Mpho Molikeng, Tlokwe Sehume, Sonkanise Nkosi, Jeanne Zaidel-Rudolph, Andile Khumalo and Dizu Plaatjies.

Considering the number of songs involved, it appears to be a modest endeavour. But the Samro Foundation’s managing director, Andre le Roux, believes that in this instance modesty is essential, especially when one considers the financial limitations of the foundation compared with institutions whose mandate it is to preserve the archive. He believes that, once the project is done (after two years), it will represent a gauntlet to be picked up by tertiary institutions.

“When I started here [in 2006], we had what you call a serious music archive,” he says from his Braamfontein office. “The Western archive was known as ‘serious music’, so I took my key and I scratched out the ‘serious’ and it became just a ‘music’ archive, at least in name. Everything else, like jazz and indigenous music, had been termed ‘light music’. That was about the weighting of the people who were running the archive, who weighted it in favour of classical music.”

Le Roux tells this story to explain his view that, before one starts on ambitious projects as an organisation, backlogs that exist in the historical canon need to be brought up to date. In effect, he says, the internal work done in attempts to balance the scales marked the first phase of the archive digitisation project.

James French, a manager at the Samro Foundation, says one of the problems with Western staff notation is that it doesn’t perfectly reflect African music. “There is a debate about the suitability of this approach, but it is like the ABC of the music world, and we are trying to make this project available to musicians around the world.”

He says the Samro music archive is home to thousands of scores, initially given by composers as proof of copyright, but this was no longer required as recorded music became more available. He said they were in the process of taking songs online so they can be purchased, and composers can earn some revenue.

Mnyani says that another interesting aspect of the project for her is that it will bring to light ceremonial traditions of cultures rendered invisible by having been left out of South Africa’s official record.

“Some cultures don’t have the privilege of being represented in the official language count,” she says. “The Balobedu, for example, are often confused with the Pedi people. The project will include some of their songs.”

So far, the project has only completed three songs, because the process involves consultation with people already doing research in the field.

“Mpho Molikeng, for example, has a huge library and we have to ask to get some of that music from him, and he has to ask the people he recorded. So there are those ethical issues,” Mnyani says.

Other songs will include those popularised by Bavikile Ngema, who often sings accompanied by uma-khweyana. He does some lesiba-based music songs, bow songs by Venda male and female players as well as some Khoisan children’s songs.

So although cultural rites such as intonjane continue, though not as frequently as the ulwaluko ritual, the nature of how they are conducted continues to change.

“The culture of singing at these ceremonies is disappearing [with the passage of each generation],” says Mnyani. “People die or get old and forget. Nowadays people tend to use DJs.”

I’m reminded of a ceremony I attended recently in Soweto, in which the family members argued about the appropriateness of loud house music in the afternoon, after the formal rites had been concluded. As the people later drifted home, in different states of inebriation, it dawns on me now that not once did I witness those in attendance united in song. In future, they might employ a DJ to mix them their cultural dirges.