'Sasol has been languishing in a narrow range without clear direction'

Petrochemical company Sasol was touted as a good investment for 2018 at the end of last year, but a strengthening rand and cheaper oil prices are changing that prediction.

One of the country’s biggest companies, with a market capitalisation of $24.9-billion (R266-billion), it has also faced a backlash at its annual general meeting in mid-November from shareholder activists who raised concerns about Sasol meeting its environmental targets.

Sasol had a “madcap year”, veteran stock-broker David Shapiro said.

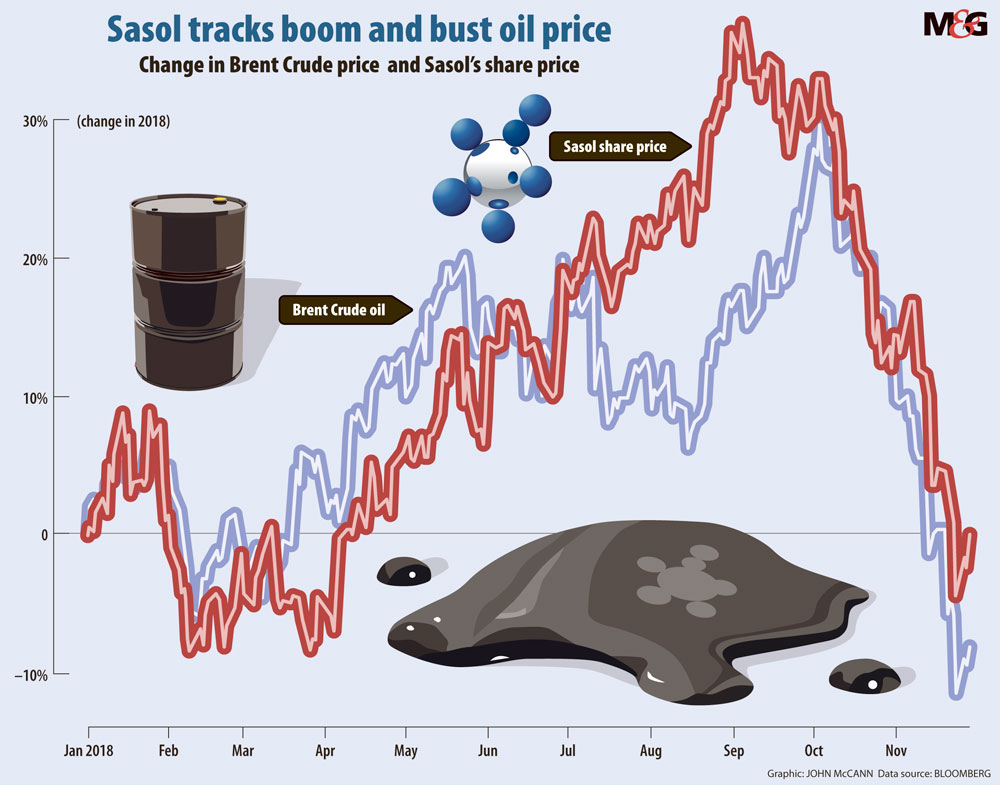

The stock, which has its primary listing on the JSE, rose to R578 in September from R386 in February, a 40% gain, before dropping to just over R400 a share. Economists have attributed the decline to the strengthening rand and declining oil price.

“For the last three years, Sasol has fluctuated between R360 and R460 a share because of concerns of the global economy. This year, we get to break out all the way, only to fall back to the space before 2014,” Shapiro said.

In June 2014, Sasol shares were selling for about R640.

The benchmark Brent crude oil price rose to a high of $85 a barrel in September, dropping to a one-year low of almost $60 a barrel this past Friday, which Bloomberg attributed to concern about an oversupply.

Shapiro said: “Sasol is a victim of fluctuations and volatility in the oil price. Opec [the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries] isn’t sticking to its production agreement.”

Oil demand is expected to top 100-million barrels a day next year, according to the International Energy Agency, but for the past week both Russia and Saudi Arabia have been exceeding production expectations and prices have declined. The two countries are the world’s largest oil exporters. According to a report by Reuters, Saudi Arabia’s crude oil production was at a high 11.1-million to 11.3-million barrels a day in November. Saudi’s average crude oil production is 9.9-million barrels a day. The two countries are expected to meet at the G20 summit in Argentina this week to discuss the oil price and Opec is expected to meet in Austria on December 6, when a decision to cut oil production is expected. But Reuters reported there are concerns that United States President Donald Trump might put pressure on its Saudi ally not to cut production to keep the price down.

Sasol said in a statement released last week that the decline in its share price was expected to end soon and promised stronger earnings than those of 2017. Sasol credited this good fortune to the “satisfactory performance of its global assets”.

Its chemical plant project, Lake Charles in Louisiana in the US, which has cost more than $8.9-billion, is expected to deliver good returns in the coming months.

But this depends on the price of chemicals such as ethylene. “Lake Charles is going to suck more money, but will pay off in the long run, depending on gas,” economist Mike Schussler said. Sasol’s head of communications, Alex Anderson, said that, once the Lake Charles project was fully commissioned, it would represent 35% of Sasol’s total assets.

But Shapiro warned that commodity-based businesses were very difficult to read.

“Sasol has been languishing in a narrow range without clear direction,” he said, referring to the declining oil price and stronger rand in the past few months.”

“Sasol was one of the big companies on the JSE. But, since the beginning of this year, the JSE has been down 15%. It had been held up by commodity-based companies such as Glencore, Amplats, Anglo, BHP. Sasol was one of the biggest supporters when it was up by 40%.”

Analysts have pinned the JSE’s decline on uncertainty about expropriation without compensation, elections next year and the general downward trend of emerging economies, following crises in Turkey and Argentina.

Sasol’s effect on the environment is also a growing concern. At its annual general meeting, shareholder activists challenged its executives about its commitment to the environment. Sasol countered that it was doing what it could to mitigate climate change by implementing a carbon budget.

“In total, our South Africa operations budget contemplate a limit of302-million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalents over the next five years, making provision for growth. To date, we have used 115-million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalents of this budget and are well within our limit,” Anderson said.

He said Sasol monitored the air quality in the areas surrounding its operations and subscribed to the World Health Organisation’s 2005 international guidelines on levels of sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxide.

Sasol had spent R25-billion over the past 10 years on projects aimed at improving the environment around its operations, he said, adding that its short- and medium-term plans, which included integrating renewable resources into its operations and potentially decarbonising South Africa’s energy sector by using natural gas resources, showed to its commitment to fight climate change.